For almost twenty years, the German artist Lukas Duwenhögger has lived and worked in Istanbul, a city whose plush, miscegenous heritages, both intellectual and visual, pervade his paintings and come-hither installations. Even for his admirers, his art — radiantly colored and populated with an array of characters who might have exited a Ronald Firbank tale or awakened from Proustian slumber — eludes easy reckoning, in part because it has been exhibited, until recently, mostly in northern Europe (Germany, London). But once seen, it casts a powerful spell that makes most other contemporary art seem hollow, a husk with no succulence.

Arriving early in the day to see ‘Undoolay,’ his 2016 survey at Artists Space in New York (a related exhibition appeared as “You Might Become A Park” at Raven Row in London), I quickly jettisoned a long list of things to do in order to spend the hours I had alone with it. There was so much pleasure; I had so many questions. I wrote to Christopher Müller at Galerie Buchholz, his longtime dealer, and, after nixing the idea of trying to do an interview by telephone across five-odd time zones, I e-mailed a letter to Duwenhögger care of a friend and neighbor of his named Cemal, who would print it out and deliver it. (The artist does not own a computer.) His responses — from Istanbul and then, later, from Athens, with assistance from Sylvia Kouvali of Rodeo Gallery — arrived by e-mail as jpegs of both handwritten and typewriter-composed pages, sometimes accompanied by drawings, collages, or newspaper clippings. Although large gaps of time have fallen between some of these epistolary volleys, attributable to changes in psychic weather, miscommunication, and various professional and personal longueurs, we’ve been corresponding for almost two years.

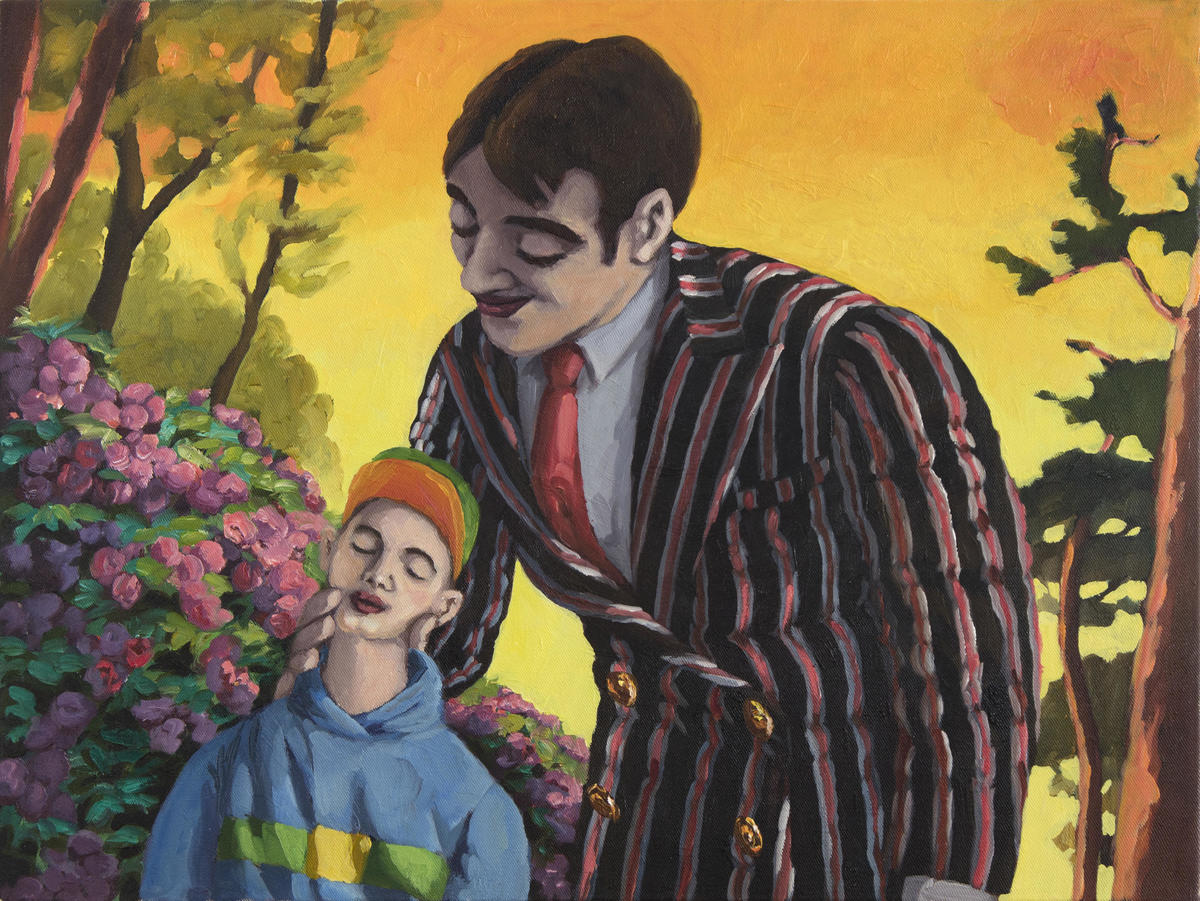

While matriarchs, grandes dames, and anandrous aunts make vital appearances in Duwenhögger’s paintings, there’s a certain regard reserved for men who work in service industries, professions that require a knack for nearness: waiters, tailors, hairdressers, pool boys; barkeeps, palace guards, postmen, clerks; busboys, delivery men, gardeners, and glaciers. Touch and the prospect of touch — proximity potential, both touching and being touched — fill Duwenhögger’s paintings. A hairdresser dallies at his station; perhaps soon his scissors will hover, a lock of hair held tenderly between fingers, a cape draped to shield the body from stray clippings. A tailor sighs, imagining his hands smoothing the hang of jacket or shirt on wide shoulders, or gauging the fit of the inseam.

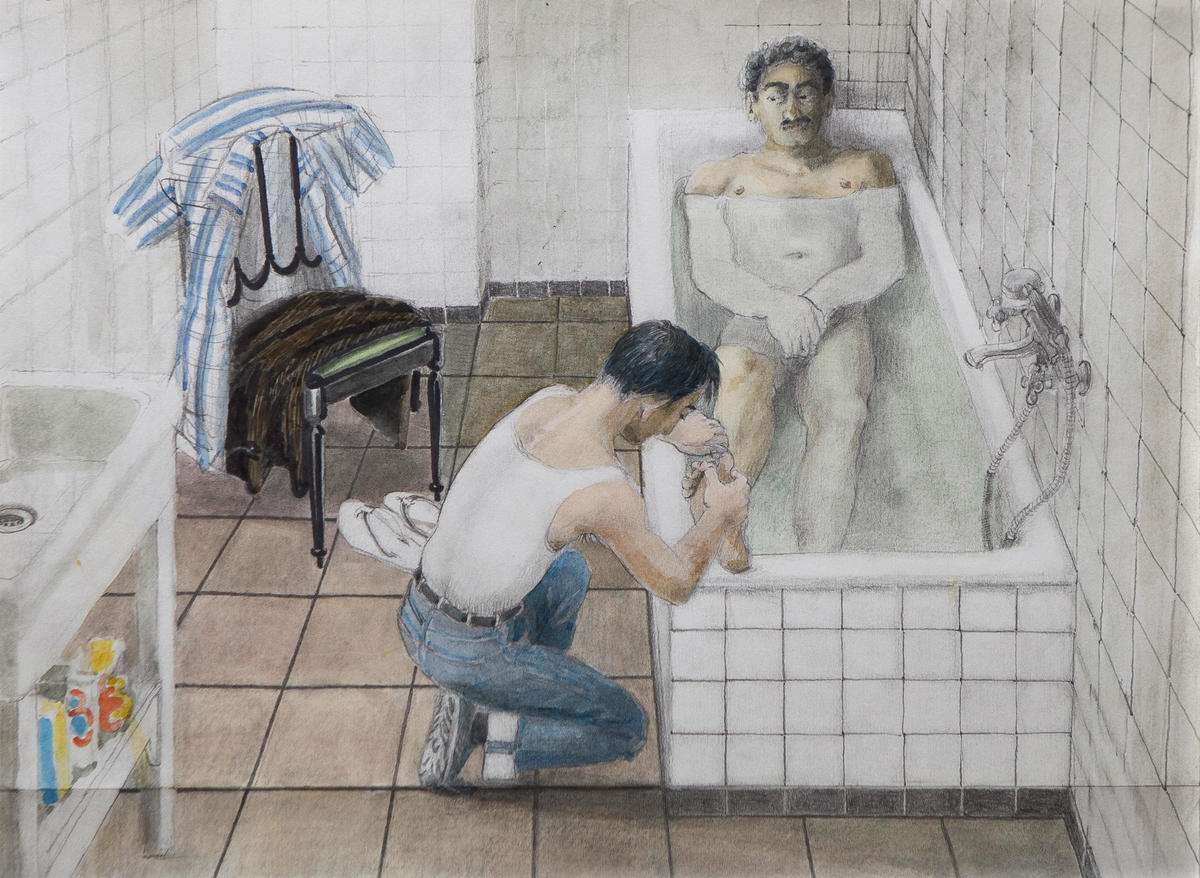

Consider Tending to the Feet, a 2014 drawing, pencil on paper, in which the artist brings so many talents gently to bear. A bathroom scene — white-tiled walls, the floor greige and gridded. A tub filled with water, the water filled with a lovely man, mustachioed but otherwise smooth. The water line lapping at his nipples, the bather folds his hands over his crotch, his left leg raised out of the water, heel resting on the tub’s edge. Another man — belted blue jeans (cuffs rolled), white tank T-shirt — kneels to clip his friend’s toenails. Below his soft, jet locks, the one being groomed has a quizzical look, his thick eyebrows slightly raised, his mouth not finding quite the right words — perhaps he’s never had someone attend to him in this way before? Only a small part of the groomer’s face in profile can be seen, but care focuses his features, bearing. Did the bather take off his clothes himself, or did he allow his friend to undress him, while the water was being run? There is a chair in the corner, a short-sleeved shirt, white-and-blue plaid, summery, hanging lightly on its back; a pair of slacks drape across its green seat, white flip-flops line up beneath it. Tending to the Feet typifies Duwenhögger’s soft dramaturgy, in which scenes imbued with erotic possibility are rendered with a facility that makes the unerring seem impromptu, and the act of painting itself is revealed as speculative and alluring.

There are still more than a few things one might ask of Duwenhögger. Is art a service industry? Might his relocation, decades ago now, from Berlin to Istanbul be considered a pointedly resonant inversion of the Gastarbeiterprogramm? How did AIDS alter his pursuits? I never got around to posing these questions, or to delve into crucial asides on various subjects (the novels of Edith Wharton, Fassbinder’s melodramas, the aftermaths of colonialism), but then, it is not clear that our correspondence has ended.

— Bruce Hainley

A note on the text: ppp stands for pedantic, parsimonious, petulant: it is the anal condition in psychoanalysis.

July 31, 2016

Dear Herr Duwenhögger,

Christopher Müller was kind enough to arrange this way to write a letter to you.

Your exhibit at Artists Space in New York transfixed me with its strange power. Based in Los Angeles, I had a single day in Manhattan during the run of the exhibit and had planned to see many shows, but I started with ‘Undoolay’ and never made it anywhere else. Although I knew your work by reputation, I had not had an opportunity to see it in person until last summer in London.

I am in the process of working on an essay about some aspects of your work for Artforum. I had written Christopher to ask some questions about a few specific paintings, and he suggested I contact you, something I am usually wary of doing in the midst of trying to wrangle any kind of language to an artist’s work — but the fact that no one seemed to address any of these questions in the critical texts on your work dismayed me and tempered my usual wariness.

I will try to keep these five questions brief and specific.

1) In looking at Perusal of Ill-Begotten Treasures, 2003, I wondered if you (ever? often?) do an underpainting of pink? I noticed a rosy glow beneath the man in the camel-hair jacket sitting on the newspapers as well as pink edging the interior of the fur cape of the man sitting behind him on some kind of wooden box.

2) Was your extraordinary film, From Cotton via Velvet to Tragedy, 1999, shot immediately after your move or right before?

2a) The protagonist says about a particular male friend, shown in photographic pictures within the film: “I cannot help myself for loving this man till the end of my life. He was my best friend, and he died of AIDS. His name was…” I wanted to be sure to have the proper spelling of his name, which I could only grasp as something like Ammi Valet, which I’m fairly certain is wrong. What is this person’s name in the film, and, despite the construct of the film, was he an actual loved one in your life?

2b) I have the exact question about the woman shown in a related sequence of the film, Irena, whom the protagonist says was his “Misia Sert.” Have you made paintings of either of these figures?

2c) Was the painting Room for the Student with a Sense for Beautiful Things, 2002, made for a particular screening of From Cotton via Velvet to Tragedy or were that film, Francesco Rosi’s Hands Over the City (1963), and Room… brought together for the first time at Artists Space?

3) Picking up from some of the questions from Cotton via Velvet, I had asked Christopher about the boy on the pier in The End of the Season, 2007-8, and the man in Bedava, 2001-3; although I could easily be mistaken, these paintings convey that these people are known to you and cared for — the style and attentiveness of the brushwork would seem to clarify this for any viewer. (In Bedava, I had wondered about the dog, the dog’s collar, and the frame, too.)

Do the models for these paintings sit for you or are the works based on photographs or from some combination? In terms of the manner of their painting, a certain almost verité directness, how do you see them differing from, say, Perusal of Ill-Begotten Treasures or Choreography for Three Men, Two Brooms, and Caution-tape, which seems to be in or of another (more fantastic?) mode.

4) I told Christopher that in my research I read that Botanical Garden, 1992, was “based on a Nazi youth poster.” Christopher informed me that you’d told him that it was based on a press photo depicting a scene from a concentration camp, but I still wondered about both the source and its transformation in the painting.

5) Finally, treading very carefully, I read today that the chargé d’affaires of the German embassy in Turkey was summoned to the Turkish foreign ministry to address the anti-coup demonstrations in Cologne over the weekend. Your time in Istanbul coincides with the arrival of what can be referred to, in its various manifestations, as Erdoğanism. How do you think the recent events in Turkey change the vantage of any thinking viewer of your work?

Of course, a response to any of these questions would be greatly appreciated, but I would understand if that proves too burdensome.

I hope this e-mail finds you safe and well.

With my best wishes,

Bruce Hainley

August, 2016

Dear Mr. Hainley,

Your carte blanche for a more permissive timespan had a disinvigorating effect on me… But then — in that heat! And your questions! Especially 5) with the “thinking viewer” under “Erdoğanism”!

To “wrangle any kind of language to an artist’s work” is admittedly not always a success, but I have often, with insistence and deliberation, foregrounded my language-relations, if not outright basked in them, often courting disaster. I think that mostly my own outpourings about painting tend to be almanacs of anecdotes. But these aspects have gone all but unnoticed.

1) I’ve never done an underpainting of pink (from now on I might try that one). Sometimes of a deep cadmium yellow or Mars orange, but then only in paintings where you can hardly see it anymore; as in Celeste… (the elephant). Perusal of Ill-Begotten Memories was made on plain white.

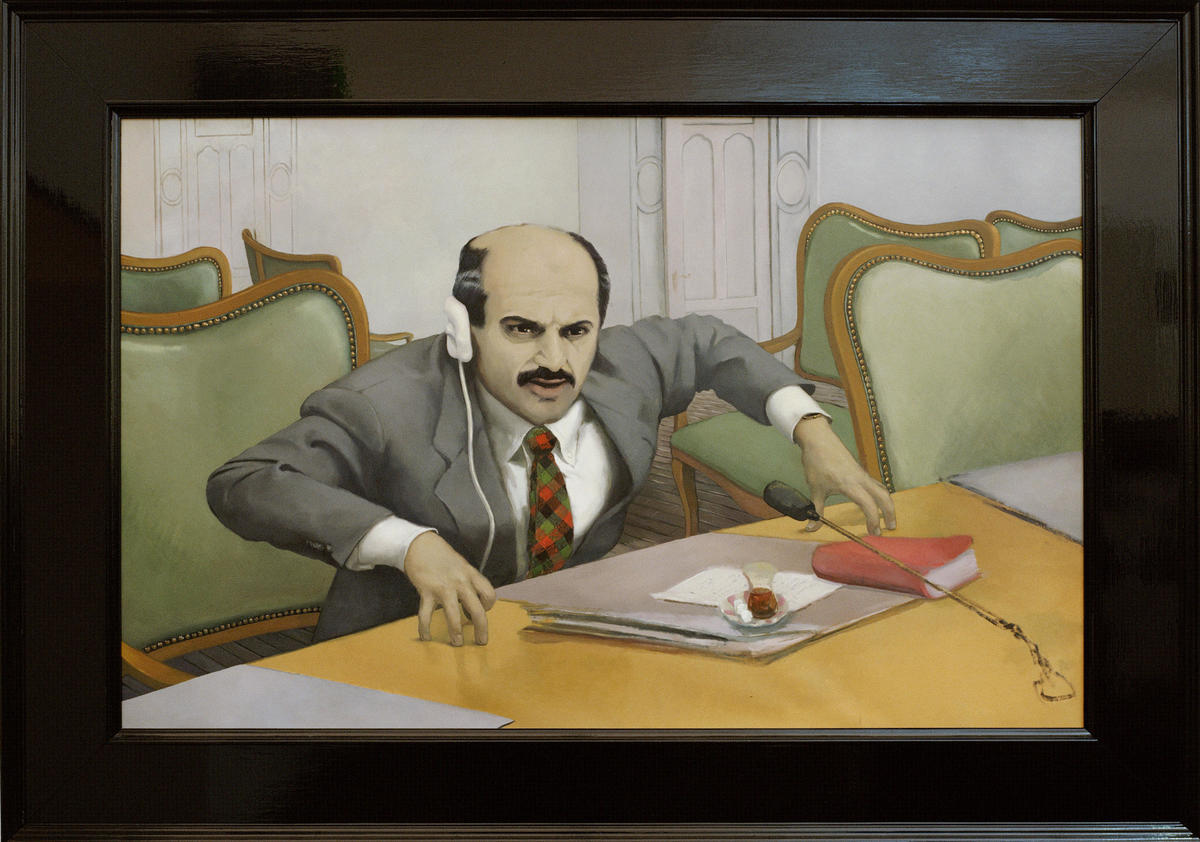

The thing is that as I became more nuanced over time I began to understand more about the reverberations amongst the colors themselves, and about the difference of colors that sit on top of a support and colors that are inside a material, like in a fruit, a petal of a flower, a skin, a fabric. It has to do with the difference between paint and dye. You can simulate that deep shine with an underpaint. Adolf Menzel, Carl Spitzweg, and Carl Blechen were very good at it, but with that technique you have to work fast and be able to let things go — which, thanks to my cursed ppp-condition, I’m hardly ever able to do, except for example in the microphone of The Rift, or in the teacher and the foot of the board in Impertinence. But my pedantic impediment to letting go is not the only force to hold me back from the undisputable joys of that technique: it is that a technique is a trick, a master-device, which is against the spirituality of a work, because the perils of training and authority and its attendant system of evaluation and social positioning — in short, the much cherished “skill” — is never far away from manipulative dissembling, self-congratulation, and customary lying. And bad company.

Conclusion: Pink was added on top, but made to appear as if coming from inside, the ground. It is the touch when everything falls into place and peace is achieved.

2) THE DATING IS WRONG. The film was made (in total seclusion) in the winter 1989/90 in Düsseldorf, actually while I was packing up for my move to Berlin (away from the masters). All my neighbors there were Moroccan, and it’s their children’s voices you hear diegetically. (Or is that the right word?) So this film has no goddamn Istanbul in it… Yet, given that I was initiated to that city in 1969, at the age of thirteen, and subsequently witnessed its darkest times (1978/79/80), and given that I moved here sixteen goddamn years ago, it can also mean that I am since a long time a goddamn German exclusively by national denomination. No bad feelings, only Miranda Goodbye. What I deem to be important here is that the video was done in the wake of what I would call the ripening of my political consciousness, at the moment when the failure of the academic system (in Germany — only in Germany?) had become fully graspable, and I decided to move to Berlin instead of New York, the destination of any “ambitious gay artist” of the time. Back then I feared nothing more than Berlin, the cold, dark, unflinching capital of the cracks in the German plaster (now painted over — thanks Berghain). But it turned out to be the hunger artists’ paradise (for a while) and little gay Turkey (for another while), and it brought me back to Istanbul, where, despite the severest warnings, I came into full bloom and continue to flourish to this day, despite your “thinking viewer and…,” “Erdoğanism,” and “vantage.” Istanbul is my life, my love, my knowledge of the world, my everything, my salvation. That does not mean that Erdoğan (and his ocean of bootlickers) is not there; it means that you have to witness the rape of the city and the country in the hegemonic global style, which is based on the western model of affluence, exploitation, and power, as well as the use of religion as a tool of domination. Yes, you bear witness to the destruction that Westerners have gotten so used to that they hail it as a superior model. If you, Mr. Hainley, have ever loved this city, I hope my words make you cry and regret that you have brought the topic up so flippantly, so academically. But where there is true love there is truth in love: unwavering. And for the “thinking viewer”: as Patricia Highsmith put it, you don’t do something with someone else’s pleasure in mind — your own pleasure is what drives you.

Conclusion: Let’s drop No 5 in advance.

Back to

2a) The name is Annibale, Italian for Hannibal. But the true Annibale was called Asdrubale. We were both outcasts. That was in Rome, 1981–83. And like all outcasts, my beloved Federico Fellini put him on his payroll for a time (late, lesser work). He did not die from AIDS. He committed suicide, hurling himself from the window of his room, carved into a rock that was the foundation of the suffocating medieval smalltown that killed him. God bless the beautiful man!

Of course there is more to follow — I wonder how, since I’m going to Athens tomorrow — but I’m gonna find the means.

Meanwhile, all yours

Herr Duwenhögger

Amorgos, 31.8.2016

Dear Mr. Hainley,

We have stopped at 2a — now comes

2b) I have never made paintings of these figures. As for Irene — presumably any gay man had, and has, substantial relationships with women, but I’ve always found this kind of sisterhood highly contested by the masculine/feminine stratification, with its inbuilt class adherence. The female impersonator/transvestite was always low-caste and his feminine aping despised by ramrod and dyke alike. And the gays always bullied out the lesbs in the Berlin Film Festival. Between fights they posed as sisters — the faghag and the fruitfly. But when it came to the real conflict, the power was in the hands of the macho-bourgie-bourgie-gay mafia (reeking of assimilation) who had never been interested in feminism to begin with. Let alone anarchism.

Irene — the entire movie, for that matter — stands in for the suppressed feminine in the gay struggle (before it got mashed into queer). (I’m talking about Germany.)

2c) Again, the dating is fatally wrong! Room for the Student with a Sense for Beautiful Things was conceived and made (my brother, a carpenter, did the woodwork — I did the curtains and upholstery) in 1997 in Berlin for a group show that we organized. We meaning a group of artists including: Janet Burchill/Jennifer McCamley, Antje Majewski/Martine Maffetti, Ull Hohn/Lukas Duwenhögger. The slashes indicate who shared a room with whom.

But it was, indeed, combined with a film screening for the first time at Artists Space.

On other occasions there had been, variously, a book, flyers, a bouquet of cornflowers, and a poetry reading.

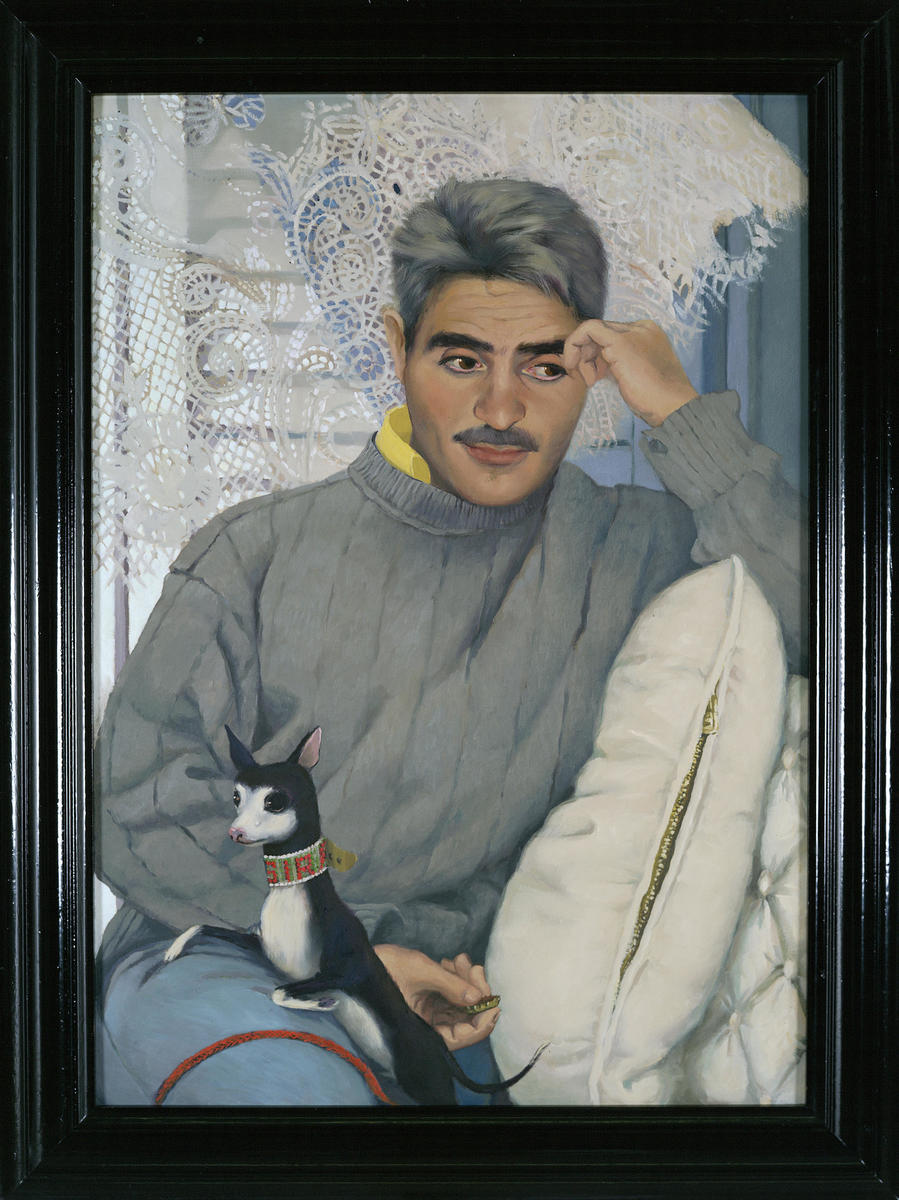

3) You are not mistaken about the boy and the man.

I met the boy, Burak Toraman, when he was thirteen, fifteen years ago, which makes him twenty-eight now. He was one of the three sons of my former downstairs neighbors, the middling one. We are still friends. He wanted to learn a handicraft, but instead followed their wishes and became, like his brothers, a customs clerk. He is not attracted to women and I don’t know for how long he will be able to endure the pressure to get married. Also, miraculously, he has not yet been drafted for military service. He made me come with him and his friends to Burgaz Island, and on one occasion, when the vagabond dog sought his caresses, he asked me to take a picture of them together. After a while, that picture struck me as such a radical take on the so-called centerfold, given his fierce self-confidence and knowingness about his desirability, up to a point where all its goddamn desire-drama is turned into comedy and the crudeness of factuality becomes an uprising against kitsch, like in Manet’s Olympia. For using this image in my painting, I gave him the equivalent of $1,000. He paid off his debts with that, and you better don’t ask me what they were.

As for your verité-brush: we have been so many times undressing together, sharing the same bed, swimming together, and, like in any close-knit artists’ group, style orthodoxies were always de rigueur. He followed the advance of the painting with electrified interest and with naïve dismay. As I was paying so much attention to the background, especially the shadows on the eroded concrete, and never to his exuberant body, his impatience to see it materialize knew no bounds. He called me inept, my preoccupations — I mean, what! — mistaken, an affront to the centrality of his monumentality.

To change the subject — the gas-flasks are not fantasy, they are there next to the sea; they are stored and traded from there to the inhabitants of the island, by horse cart. They are a remnant of what you call the more fantastic modes of Choreography for Three Men, Two Brooms, and Caution-tape or Perusal…, but, as in those works, it depends on a factual existence. And this existence is a very violent correlation/irreconcilability of a domestic, contained peace relying on the exploitation of sources of energy to create warmth — WARMTH! — and comfort.

Bedava, 2002, is a portrait of Mr. Şener Karapınar (the i must be without a dot here), a man of strength and tragedy who had to spend fifteen years of his life in prison for the fatal stabbing, as a boy of eleven, of another boy in the orphanage where his parents had dumped him. He is an all-around builder and repair man, supervising the maintenance of the properties of the Greek Patriarchate, including churches, cemeteries (he lives in one), monasteries, etc. He is a father of three (one disappeared) and slowly drinking himself to death. He thinks life in prison was better.

When we were lovers, the dog, a Chihuahua called Willy, was brought to Istanbul by the painter Katharina Wulff in her handbag. She had dosed him with homeopathic sleeping pills, and as she alighted from the airport where we had gone to pick her up, Willy regained his consciousness and immediately fell in love with Şener who, from then on, carried him around in his arms like a baby.

The portrait is based on a picture I had taken before the arrival of Willy. Of Willy I had never taken a picture. But as I wanted to recreate their bonding — and Willy was gone — I recalled the representations of exotic animals from the Middle Ages to the Baroque that had been based on descriptions and sometimes drawings of the early European colonialists and explorers. So I decided to use my mnemonic faculties instead and let realism be realism.

The collar is made with a crocheting technique using the tiny glass beads that convicts learn in prison. (This technique turns up again in Sunday Afternoon.) Şener excelled at it and made a wristband for K. W. with the word “huzur,” meaning “longing.” In the dog’s collar the word is not sir but sır (again the i without the dot) which means “secret.” It’s one of the many little games of hide and seek I played for my own entertainment and the satisfaction that can be derived from showing that “accessibility” or “communication” or “information” etc. are vain illusions.

The title Bedava means “For Free” and connects with the beer-bottle top Şener is playing with in his right hand. At the time there was a promotional campaign for Efes beer where you could collect a certain number of these tops that had an imprint on the inside, and when you got the required number together you got a six-pack for free. Şener was adamant about it and dismissed me as being careless and inattentive to the advantage.

All the signs of the “more fantastic,” if I come to think of it, are standing in for a feeling of danger and threat. Regarding not only homosexuality but also class, I have been brought up in a highly manipulative “between-the-lines” environment, and I have sought visually to reproduce that distasteful situation as a revenge; to confront them with my own codings, to become, in this respect, fantastic. But I no longer believe in that… that I can be more closeted than them.

That is, I believe, where language may come in almost as a duty. To find or create freedom, autonomy, poetry in this medium of dominance, and to consciously appropriate it, as so many great people have done, as a means not to be spoken about but to speak out on your own behalf. I’ve always detested the artists who are complicit in the chronic underpayment of language workers who oil the wheels of their reification.

The frame: I’ve written about the frame-question in Picpus No. 13, Spring 2014:

I don’t know whether Lucien Freud’s portrait of Queen Elizabeth II comes with a frame but the pictures I have in mind always do. Like interpreters or translators, frames are one of the many unacknowledged forces in the mechanics of a society. They form little catafalques you trot behind while thinking about being somewhere else. They stoically contain the fickleness of their subjects and calm the shaky ground on which these idols and temples stand. Bleak it may be, but they provide shelter for their flag-like readability, endearing as stone.

P.S. The paintings are a combination of all sources you mention — plus memory and outright improvisation…

4) It’s based on a picture I clipped from a German daily: A scene in one of the hundreds of concentration camps the Nazis established long before 1941 all over central Europe. Amidst the terror it shows a scene of tenderness, which reminded me of my wish in early childhood to be caressed by a man, being even kidnapped, sexually loved, abducted from that hellish modernist domesticity with all the Bergman/Cold War/Swedish insufferable Herrenrasse pseudo-Socialism. I was always deeply troubled to have used this picture in that way — and I think you are the first one ever to have enquired about it. Thank you!

Good heavens we’ve done the 5) already