May 16, 2017

Dear Lukas,

At some point today, Donald Trump and Recep Tayyıp Erdoğan shook hands. They met to make deals and ignore everything already crushed and continuing to be crushed by their relentless power grabs, all of it assisted by the endless toadying of too many officials around them. It was reported that Trump, among other things, mispronounced Erdoğan’s name. Much of it was nothing other than a photo op for “brushing aside tensions,” as the New York Times put it, one day after they’d posited the hit Turkish television series about medieval battles, Diriliş: Ertuğrul, as a fit way to understand, well, something like today, in light of Erdoğan’s referendum speech on the bitter “struggle between the crescent and the cross.”

Other than to note the date — 16 May 2017 — I’ll refrain from trying to say anything else on that, other than to acknowledge the dark fact of their state meeting. But it did make me think that it might be good to pose a few more questions, to lend, if you are amenable, something fresh and au courant to our epistolary proceedings.

1) Ronald Firbank, Edith Wharton, and especially Henry James, each have appeared resonantly but differently in your work over the years. How does the literary operate in relation to your art? Or, perhaps a better way of putting it — how does fiction, resisting banal interpretation, nevertheless clarify, providing useful allegories for your pursuits?

2) Mention of your recent purchase of a home in Athens has compelled me to think about the Levant and its history — the possibility of, in Philip Mansel’s phrase, an “elixir of co-existence” that enabled Muslims, Christians, and Jews to live together in cosmopolitan concordance, once upon a time… Do your paintings proffer, as much as they are perfumed by, such an elixir, its seemingly current unlikeliness making its depiction, history, and possibility all the more crucial?

3) Constantine Cavafy?

(Poetry of course — but particularly his young men, many of them “dreaming” of giving themselves “to pleasure fully,” as a relief from finding themselves out of work or having lost the coin toss of existence.)

4) In “The Clay Hen,” the short story in the publication that accompanied ‘Undoolay,’ there is this sentence, in the very last paragraph of the tale, a few lines from the end: If ever there was a self, I was nothing of the sort. How should one weigh that sentence — only a line, but what a line! — in light of the specific, vivid, variegated panoply of your work?

I have many other questions, about Seurat and Florine Stettheimer, but for now, and perhaps for Bidoun, this seems more than enough.

I hope this note and these questions find you exceedingly well.

With my best wishes,

Bruce

May 31, 2017

Dear Bruce,

Okay, our coquetry is done with — great!

I’ve returned from Athens five days ago and am now forced to fight a bacteriological infection, meaning I remain without, oh, the help of a drink — and in the face of your questions, which leave me pretty much stranded, if not incredulous. I feel so terribly remote from those concerns just right now that I can only gasp at the eagerness characteristic of my endeavors from 1990 onwards (up to when, when, when?) but which I ought to brush up with if I’m to answer you in any meaningful way. It borders upon a crisis of consciousness.

But I try — so let’s start with 1).

I went to NYC in 1990 for the first time in my life, to visit friends and find out how it felt to be there. I was on the lookout for a city to move to after Düsseldorf. (I settled for Berlin instead.) My English was nothing but perfunctory then, yet, with good old German superciliousness, I was not only ignorant of that fact but convinced of my mastery. Then came the well-deserved mortification.

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick had just published her much-acclaimed Epistemology of the Closet, a must, if there is such a thing, back then and even now. Of course, musts always do more harm than good, as I should know especially well. Anyhow, after the proud purchase was done, making me feel elevated to the uppermost echelons of the ones in the know, and I’d carried it home, and opened it, I instantly realized to my unspeakable embarrassment that I was hardly able to understand even the first paragraph.

That was the beginning of my adventure in English (ongoing, to be sure).

It took me a long time to work my way through that book, to truly absorb it, and I think I can claim that it was the only time in my life I “studied” something, in the orthodox meaning of the word.

The consequences were very fruitful. After I moved to Berlin in the spring of 1991 (before that move I did the movie From Cotton via Velvet to Tragedy, if you remember from our former correspondence), I discovered the gay bookstore Prinz Eisenherz and through sheer perusal of their shelves in the English section came to select, amongst others, the writers you mention. One thing leads to the next, as you know. And, like everything else, might become part of your life through attraction, spiritual hunger, curiosity, interest, approval, ravishment, reciprocation…

(At this point I deem it appropriate to emphasize that in no instance have I ever plunged into any activity with an arrière-pensée: to milk a material, to turn it into future references, to legitimize my own flights of fancy. This as much as anything accounts for my living in Istanbul. If I had ever longed for those foundations of respectability, it would be smoother and cooler to take you backstage and show you the strings of my cleverness. But how to disentangle what flows from where into what? And why? This makes my response to your inquiries almost painful, and why your bringing up that goddamn Tayyıp time and again — and now, even worse, that ppp-Mamsel’s “Levant-elixir” — borders upon the offensive. It was the Brits who made “sodomy” (or whatever those bastards called it) punishable throughout their empire and who are now shedding crocodile tears about a lost “cosmopolitanism.” Should an inclusion of these rancid themes be expected for the publication, as you seem to insinuate, you better hang it!

But to return: As I hope I have made clear, my pursuit of a deeper understanding of your language, admittedly highly idiosyncratic, was never motivated by the wish to achieve what people call “fluency,” that linguistic glibness which makes so much writing so predictable. There is the fact of Anglophone hegemony and its degrading effect on other languages worldwide, and often I find myself involuntarily in situations where I feel almost complicit in the mutilations it inflicts; but English, at a certain point, allowed me to escape from my mother tongue and its post–World War II limitations, and build a nest high up, exquisitely protected from the intrusive pedantry which the Germans so cherish to exercise. If that came at the price of an estrangement which led to my final exodus, that estrangement had already been well in place, much like my “Levantine” characters. And besides, groping about in the twilight of a new language (or painting, for that matter) always creates delicious wonders and allusions unattainable to those who presume ease and self-evidence. Certainly, there is a shared, implicit synesthesia in flat, still things like books and paintings, because you have to give them body and make them move in your mind. And I’ve always found the collusion of a title and a work fascinating. And then it’s always arts and craft anyhow!

TO CONTINUE

YOURS LUKAS

Dear Bruce,

A postscript to 1): After Cemal had posted it to you and I mentally waved it goodbye, it suddenly struck me in hindsight how blind I have been all these years to the diligent cross-fertilization that had taken place subcutaneously after 1990, between my blossoming sensitivity and receptiveness within the sphere of English-reading and what was going on in my painting. Had you not pushed me, I could never have seen it like I do now! And what was going on in my painting? An ever-growing attention to the sociological implications of detail and, equally, to the sociological meanings and reverberations of colors. And at the same time the expression of an apprehension, an anticipation in the figures and atmosphere of what we call “the calm before the storm.” Those were the effects not only of what I was reading in terms of content (and you know how masterfully those writers are veiling it), but also of having entered unknown territory — fractured and out of focus, constantly dissolved, renegotiated and reconfigured, constructed upon the very absence of affirmation, without a basis or permanence. Everything is a bone of contention in this state of relentless social affairs. In short, it’s what came to be called the modern condition — that old, smelly shoe, forever ill-fitting. But what a variety of smells! And if your nose happens to be as discerning as a truffle pig’s, you’ll always get the whiff of the village from whence the tramping started.

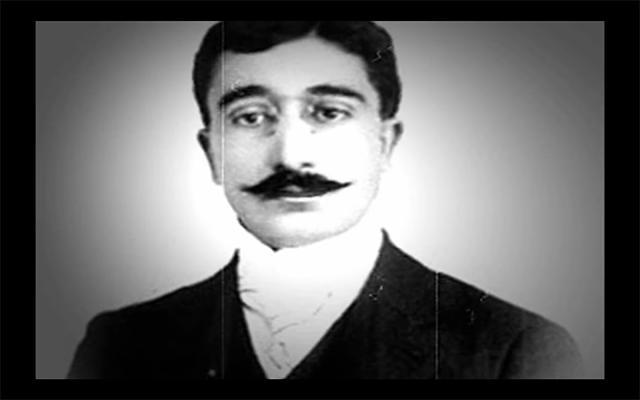

2) My work has been mostly associated with things past, placed, if not altogether outside the western contemporary, at least in an oblique or obscure relation to it. Its (enforced) outsider status, its hidden agenda, its resuscitative energies, seem to “narrate” something that waits to be decoded and properly judged. This deplorable attitude simply reaffirms Sedgwick’s insight that common, popular knowledge is simultaneously disowned and reestablished in the construction of otherness. This led, among other things, to the seriously mistaken and consequential view according to which I went to Istanbul a) to get fucked by the gorgeous mustaches called Mustafa and b) to suck out inspiration for my work and c) the two of them together.

That’s why your fishing for Levantine jewels is prickling my indignation. I’ve had my share of gay imperialists, royalists, converts to the Catholic Church, even fascists and racists and, indeed, orientalists, so whenever someone comes close to that abominable realm — like ppp-Mamsel — I just kick off my heels and run! Why don’t you give me beautiful Edward Said instead?

My own “Levant” started on the construction-sites of my father’s early buildings, homes for middle-class families (including us), and a school annex. The large-footed, strong-handed, broad-shouldered, black-haired, melancholic, musical, impetuous men from all over the shores of Europe who built them: they were the spring that was to widen into the stream and finally became the river to carry me where I belonged. They lived on the site in a wagon and burst into song when they showered from the hose. They had an empty oil barrel instead of a boxed-in, tiled bathtub, an empty bean can instead of a gleaming flush-toilet, an open fire instead of a kitchen range, and above all: they moved on before the family moved in, into false hopes and frosty doom.

One of them — an Italian — hurled a huge hammer from the scaffolding at our neighbor’s son, a boy of ten, who had insulted him with racist invective, just missing his goddamn little Nazi head by so much. I can’t tell you how much I admired him. It happened in 1962, my first year in primary school.

To be continued

Yours Lukas

Dear Bruce,

It’s a glorious day, finally, and I’m feeling pride and confidence because I can do without drink just as well — except that I miss my beloved watering holes.

Continuing with 2):

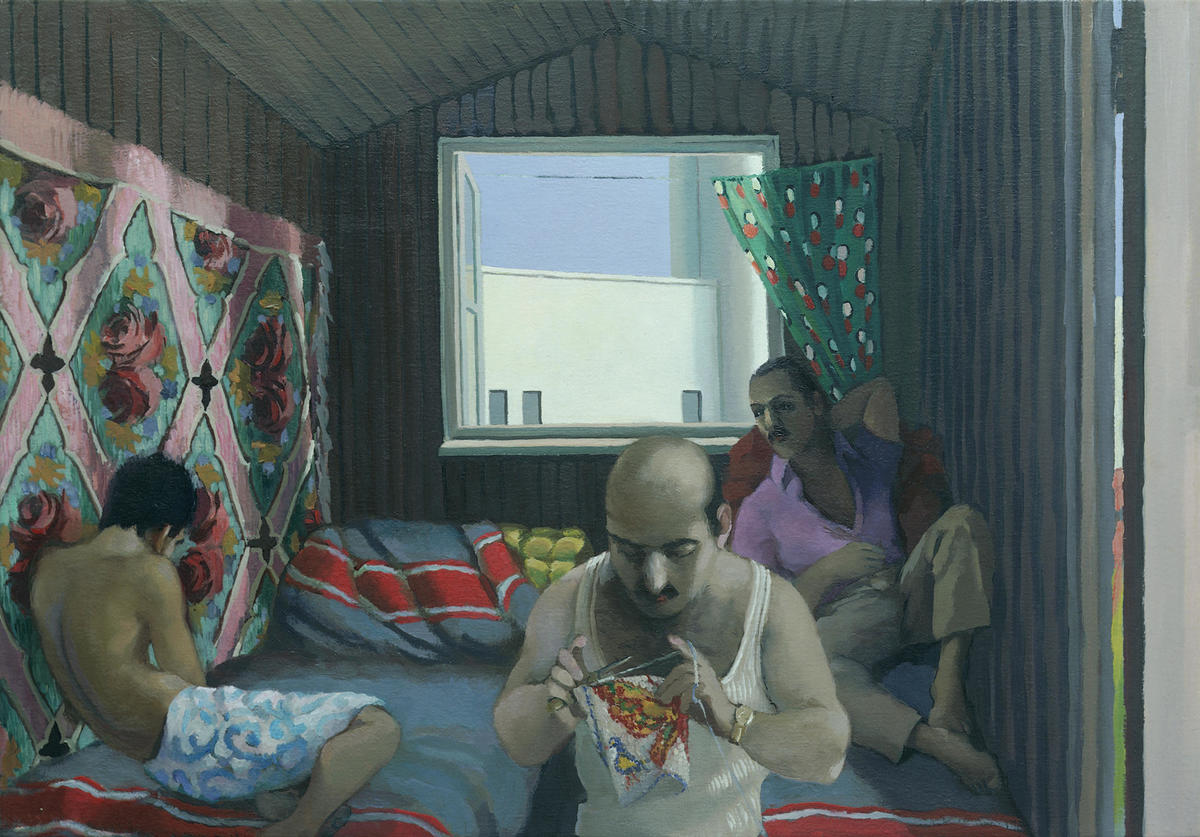

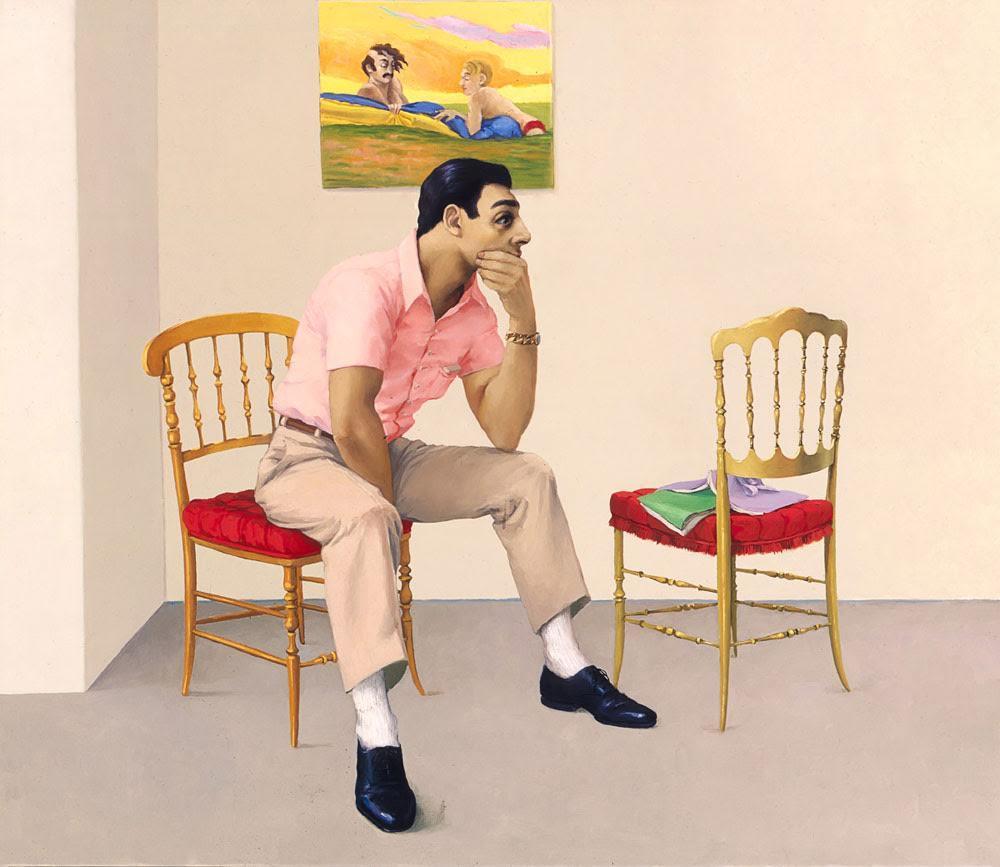

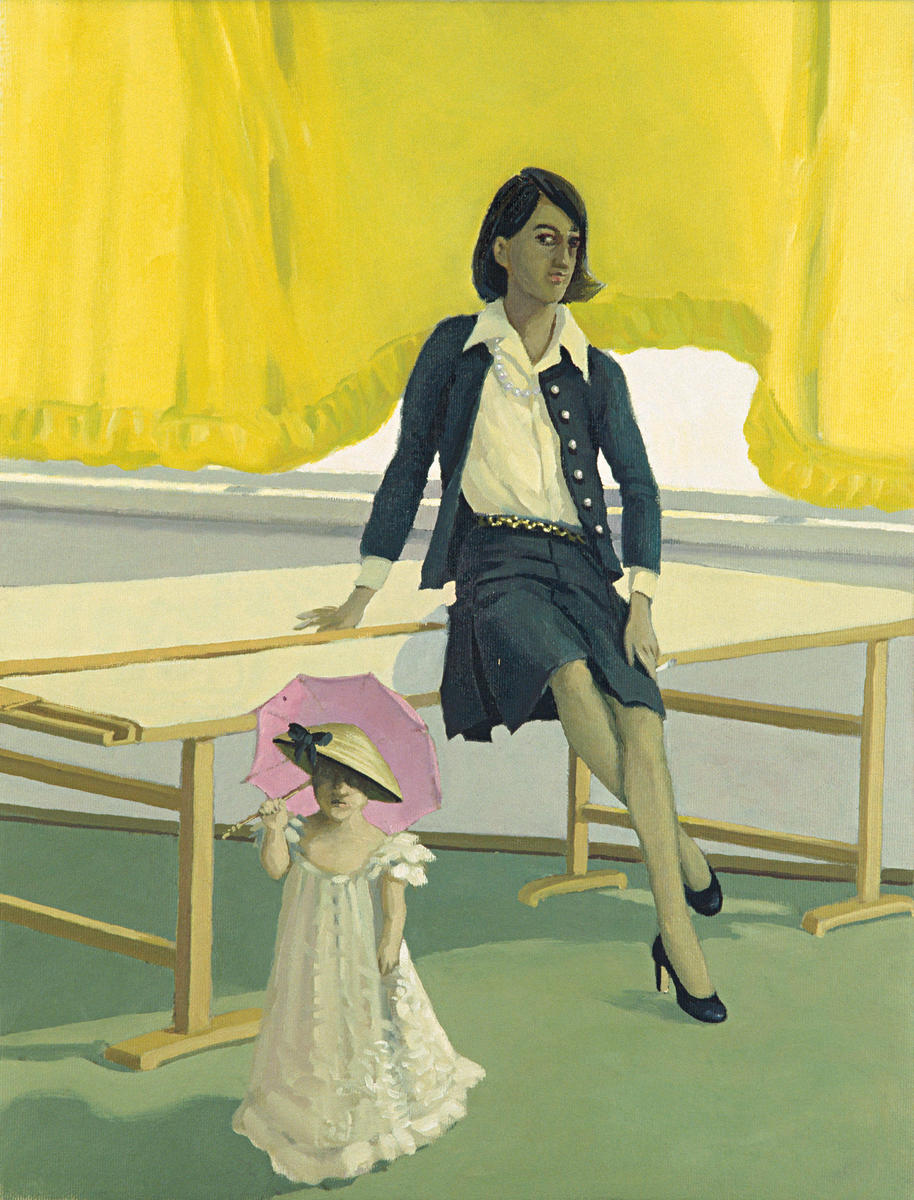

I spent my long and blissful childhood mostly undisturbed as a drag-princess (depicted in the painting Mimar Yücel). The court etiquette of my princessdom included regular visits to the workers’ wagon in full regalia. They always welcomed me with the utmost reverence, seated me tenderly amongst them, and fed me like a bird. Their departure left me devastated; yet in the end it ignited a longing so forceful that nothing could hold me back on my way to rejoin them. (See also the paintings Sunday Afternoon and We Must Believe in Spring.)

I don’t tell you this story merely to be entertaining (which nevertheless I hope to be), nor to upholster my biography, but to insist on personal experience as opposed to a construction hammered together so as to fit into someone else’s narrative. In the face of the all-pervasive, viscid, pre- and mis-conceptions about the “Orient,” “Levant,” “Middle East,” etc., it seems right to me to scale down, to steer clear of the neo-colonial newsreel, and to stick strictly to one’s own tools. Even though I’ve never been a guy with a gift for epic vistas, I bemoan the disappearance, nay, the destruction of the world you fancied to mention more than you can think. But I’ve become acutely aware that historicist approaches in the vein of ppp-Mamsel are not only parasitic and tedious in their zealotry — they inspire nothing but a self-flattering connoisseurship, especially amongst the wealthy who have greedily collaborated in the annihilation of the plenitude they purport to miss. The preciousness of what no longer exists thus becomes an investment in their superiority and a legitimization of their exploits. As Istanbul is being gutted under our stupefied eyes and her soul is taking flight, huge, ornate placards, designed to make you complicit in the crime, are instructing you that “History is yours, the future is yours” (Tarih senin, gelecek senin).

To be continued

Yours,

Lukas

June 10, 2017

Dear Lukas,

I hope your bacteriological infection is no more, and that you’re feeling fit and fine, discovering new ways to get a beloved watering-hole vibe, without the “water.”

Early June in Los Angeles remains one of my favorite seasons in the city. Too many don’t know that L.A. does, indeed, have seasons; they’re just not as dramatic as other parts of the world. Right now, we’re in what’s referred to as “June gloom”: grey clouds and cool breezes until past midday, when the sun shushes all the gloom away and heats things up until sunset, when it gets cool enough to desire some kind of light sweater or wrap. The jacarandas, whose purple hums against the morning grey, punctuate the vista and scatter their sticky blossoms like wet confetti.

No more of Philip Mansel and his theories; I promise to keep them faraway and steer clear of any neo-colonial claptrap.

Instead, a few questions about the close-at-hand, the daily, the studio:

1) Does your new home in Athens have a studio on the premises, or do you like to have to stroll from home to studio?

2) Do you work on a few paintings at once, or only one at a time?

3) Is there a brand of oil paint you prefer? A type of brush without which the work just won’t happen as it should/must?

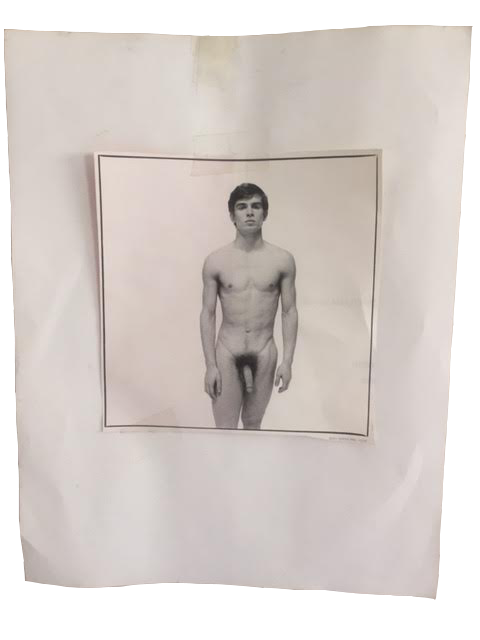

4) To the left of my desk I keep a kouros in the form of an Avedon portrait of Nureyev, clipped more than a decade ago from a magazine and taped to a piece of paper. On my desk for quite a while now is Selected Poems by Marianne Moore, published in 1935. Her poem, “A Grave,” I’ve read more times than I could count.

Other than your own works, finished or in process, do you keep any art or reproductions of art in the studio?

5) Do you listen to music while you paint? Lots of different kinds of music or not?

I hope this finds you well.

Fondly,

Bruce

A Grave

Man looking into the sea,

taking the view from those who have as much right to it as you have to it yourself,

it is human nature to stand in the middle of a thing,

but you cannot stand in the middle of this;

the sea has nothing to give but a well excavated grave.

The first stand in a procession, each with an emerald turkey-foot at the top,

reserved as their contours, saying nothing;

repression, however, is not the most obvious characteristic of the sea;

the sea is a collector, quick to return a rapacious look.

There are others besides you who have worn that look —

whose expression is no longer a protest; the fish no longer investigate them

for their bones have not lasted:

men lower nets, unconscious of the fact that they are desecrating a grave,

and row quickly away — the blades of the oars

moving together like the feet of water-spiders as if there were no such thing as death.

The wrinkles progress among themselves in a phalanx — beautiful under networks of foam,

and fade breathlessly while the sea rustles in and out of the seaweed;

the birds swim through the air at top speed, emitting cat-calls as heretofore —

the tortoise-shell scourges about the feet of the cliffs, in motion beneath them;

and the ocean, under the pulsation of lighthouses and noise of bell-buoys,

advances as usual, looking as if it were not that ocean in which dropped things are

bound to sink—

in which if they turn and twist, it is neither with volition nor consciousness.

Sep 3, 2017

Dear Bruce,

It’s been a long time, I know — I started to wear so thin, almost giving it up, especially with your Cavafy question, so irreverent, which I nevertheless still hope to return to. But now that your June 11 mail has resurfaced, at last, let’s try and be done with it. I’ll do it in jumps and twists.

STUDIO BRUSHES BRANDS OF OILS

What about stretchers, canvases, staple guns, primers, solvents, easels, sand papers, spatulas, bottles, scissors, rags (one of the most — the most — important tools of the Ingres faction)? They have a provenance too, and different degrees of appreciation. I’ve never met that fake enfant terrible of figurative painting, John Currin (“Representation is violence”; “I must prevent my children from seeing my pornographic pieces”), or that ever so politely musing and bemusing Peter Schjeldahl (in his éloge de Currin: “I have never seen such a succulent Christmas turkey in the history of painting”) but I truly wonder if you intended to test if I belong to that sort of cramp? That would be bad enough; yet, if you were serious it would be even worse. This placid, self-enamored bunch of gourmands! And that’s only one example! I only bring them up because in 1990, at White Columns in NYC, the seminal year I mentioned before, Ull Hohn pointed out Currin’s paintings to me somehow sarcastically, kinda “You have something in common, gibi.” Soon after, that stuff was all over the place, dutifully rationalized. And then a few years later he and Feinstein lived just across from Artists Space! While I was working there, their lights ablaze! As for Schjeldahl: I was a New Yorker aficionado until the degradation of that publication, that awful tragedy of our times, and pretty soon got into the know that any objections to his excretions transformed you into a minority amongst the polite. As Hu Ranran, the director of the movie Escape, says: “Sooner or later, everyone is likely to become a minority of one kind or another. No one can escape this.”

Not that I hadn’t noticed years ago, in the alentours of the so-called resurgence of figuration, how people started to fetishize their bloody quality stuff. About the same moment, I gather, that they started to talk about what and where they were eating all of the time. Whereas, as Fran Lebowitz stated, we had been talking about sex and politics! So true! For sure, there were reasons to lament a disappearance of skill, as I’ve witnessed Rosalind Krauss, amongst others, lamenting — but that, I suspect unintentionally, led to the reestablishment of the “master” and the virility of his brushstrokes, a narrative that had been responsible for the banishment of figuration to begin with. After all, it was the feminists who paved the way for the reevaluation of figuration through a critique of representation, and I definitely consider myself a member of this camp. Woe to the master who revels in the gourmandise of his courtiers, the shadow-caster upon every neighboring bloom. The equivalent in the kitchen is, you guessed it, the chef. In the academy, the professor. As I bring up the academy, I realize I have something to say about the studio. Sure enough, Katharina Fritsch is not going to cast a life-size elephant in her studio, let alone her living room — that unbelievable piece of sculpture was cast in one of the world’s most famous foundries, in the Ruhrpott, an industrial landscape where she was born and to which her artwork is profoundly indebted. But back in the 1980s, true painterly ambition needed above all reckless size and splash and you couldn’t be considered a real competitor without a studio, whether you could afford it or not. Aping the prof, no matter what. Misery was the consequence — a gnawing sense of inferiority — great to get treated to a couple of cognacs by your master! To be elected into his circle! You swallowed the stuff, desperately playing cool! As it happened, I got hold of the complete letters of René Magritte. In one he said: A studio? No — I work in the salon of my wife! Dirty? No — I’m putting the paint in the place where it belongs! The appropriation of that maxim turned out to be really helpful. And I subsequently worked happily ever after in my salons (given my numerous translocations), until the first upheaval happened in Istanbul with the reelection of Tayyıp in 2009 and things started to turn nasty. I had shipped all my stuff to Lisbon already when I was persuaded to stay by a wise man who told me that it was no good to live in the butt of the EU, and eventually I made the stuff come back. But I was never able to get back to peaceful normal amongst all those boxes — the peaceful normal that’s the true conductor to work in the field of imagination, as far as I’m concerned. Then, on a stroll, a friend of mine called Nilüfer, who knew about my being trapped amongst those walls of boxes, paralyzed, saw an office for rent and suggested I go and find out. Heaven! Maybe now I got used to a goddamn studio, ain’t never going back to salon, all the more coz having done up my place here in a fashion to accommodate friends in what I consider to be a welcoming scenario. Why not you, after all this depraved questioning? And there’s something interesting to say about my coming into contact with oil colors, as well.

The first-ever ones were given to me as an encouragement in what must have been 1979 by the abstract expressionist painter Heiko Hermann, an acolyte of Asger Jorn and the COBRA group. He had bought tons of the stuff wholesale from a bankrupt factory. I just had to bring empty marmalade jugs — that’s how it went. Then we smoked cigarettes and drunk wine. The paint’s low quality made me develop my technique out of necessity — thin layers on layers — to coax out of those miserable pastes the brilliance and saturation I craved for; which worked perfectly, given that after forty years they look as if painted yesterday. Given the all-pervading acrimony amongst practitioners of painting back then, the brotherliness of Heiko still resonates with me today as exceptional. Exceptionally erotic. Maybe he was an outcast himself — he stuttered; he was truly princely, above and beyond even an inkling of a wish to prove his standing through a sentimental gutter credibility — or he had seen his artistic affiliations vanish into obscurity. He had, if you know Hamdi Ulukaya (the founder of Chobani), the globe eyes surrounded by the delicious jungle of curls, inviting your fingers, and the ancient nose set by brown, firm, expert hands of forgotten kingdoms to defy the global enemy — homogeneity.

Later, as I continued to be luxuriously poor, I inherited oil paints from dead painters, or from former painters who had switched to video, photography, print, or installation. Think the Pictures Generation. These paints were mostly from communist countries — the GDR, Russia, China, Poland… where the orthodoxy mandated social realism, which demanded both quality and low price. I still have tubes fresh as snow from the 1960s. As with my studio, the occurrence of my buying paints is a very recent development and not indicative of my practice at large.

Before coming to an end, I want to thank you for the unbelievable Nureyev kouros: how many men he must have made dance on the ceiling, their bodies screaming. But I wish Avedon was still alive (and his times) to do a picture like that of my thirsted-for Hamdi Ulukaya. I was introduced to Rudolf and Margot in the flesh by my late gay granduncle Herman in a Munich beer hall in 1971, and Robert Beevers introduced me to Marianne Moore by way of a tome of her collected prose.

IF EVER THERE WAS A SELF

Loss of self.

This sentence is purposefully double-edged. In the context of the story’s end, it conjures the loss of self through trauma — the narrator’s realization that he — his sex ever-so-slightly hinted at through the word dostum, which is mainly used among men and means “beloved companion” — is capable of cold-blooded murder. But the if ever there was obviously throws the entire notion of self into doubt. Who, ever, wasn’t craving the loss of it? Isn’t that the route of all desire — for sex, for exotic lands, to learn something, to dance, for any kind of immersion, creation? Don’t forget that the story begins with a declaration of love and then immediately concedes that the story might be told in an entirely different way by the clay hen herself. The authority of the I, the self, is granted to be malleable. And the entire story depicts an endless concatenation of events of the widest possible range which finally collide in the destruction of a seemingly banal object, which has been charged with that monumental accumulation of human failures all along. Otar Iosseliani’s Les Favoris de la lune tells of similar phenomena — objects tied to human destiny, and suffering from it. But there is something else as well. I experienced on many occasions that what we call the self can actually be regarded as an endowment (living in foreign lands, I know very well that your so-called “I” can calcify, and that the loss of it can become second nature). Regarded as a social recognition, bestowed upon you by what they now call values, it can be taken from you at a glimpse. As Hannah Arendt observes in On Revolution, the self depends on visibility, the exposure to the light of the public, the political arena. The poor suffer not only from their material depravity, but from their obscurity, their inaccessibility to the light; from destitution in the sense of exclusion from of an acknowledged, recognized, institutionalized visibility. To shine in the light of public exposure used to be called public happiness. Let’s hope that this is why Isa Genzken once said to me that I can’t be an artist in Istanbul, away from the rambazamba of competition. When you withdraw to become “a man of letters and contemplation” — or an ascetic — renouncing the limelight, your self undergoes significant alterations as well, it mellows, sheds its scales. I find it very salutary. In the end, what I want to say is that I remain highly suspicious of the categories of the self, the personal, the individual — maybe, and most fundamentally, because the homosexual that I am will always be the definition of others. If identity politics don’t work, it’s because they rely on non- or false identity in the first place, on your being defined. No one would call themselves anything. As I see it, this profound instinct to be a member of a social body working in unison for its livelihood and happiness without the compulsion to designate, to justify, to separate, has been exploited to form a uniform. In late capitalism, so-called diversity is the new uniform. Anyone would love to wear the clothes that anyone else wears. Le cri de guerre of identity politics, “the private is public,” has always been misleading because it relies on the untouchability of an authentic self — and as far as I can see, there has never been anything like that in the history of humankind.

Yours,

Lukas

Thur, Sep 7, 2017 at 11:21 AM

:(Poetry, of course… but his boys)

Earlier on I was bringing up the hegemony of English and its often mutilating and impoverishing effects on other languages. The inherent problems of translation aside, the most damaging effect, it seems to me, is that as soon as something gets recast in that idiom — that relentless, corrosive idiom, the all-pervading illusion of accessibility, the reduction of meaning through the privileging of “story,” of literal content — it is at the expense of musicality, rhythm, sound, vision, and sense, and the implications of different idioms, historical and modern, demotic and literary, ecclesiastic and erotic, of varying topographic and social provenance, which suffuse Cavafy’s poetry. These lyrical and dramatic qualities are, to a large degree, unintelligible not only to the readers of English translations, but to most contemporary Greek readers, as well. Far from being a deplorable obstacle to a wider appreciation of Cavafy’s work, it is the poet’s very own stance and position in the world that he chose to inhabit — to sing to the few sympathetic and attuned. When you grandiloquently brushed aside poetry in your question (which I called irreverent and which, as unformulated as a shopping list and full of an almost embarrassing anticipation, I wouldn’t even call a question so much as an incitement to gossip), you opened that abysmal void where only instant gratification counts. The thing is, you made me feel you were using Cavafy as a pretext to spice up the text with some boy-elixir. Not that true artists care to be revered, but man, keep your tricks for someone else!

But to give center stage to Cavafy — with the help of the great Peter Mackridge, who wrote the introduction of my edition of the Collected Poems (Oxford World Classics, 2008) —

His name Konstantinos Kavafis is a combination of the Latin Constantinus, the founder of the city of Constantinople and of what later came to be known as the Byzantine Empire, and the Arabic-Turkish word kavaf, meaning dealer in cheap shoes. Cavafy lived in a modern trading town, founded upon cotton with the concurrence of onion and eggs (E. M. Forster). Istanbul is primarily a city of trade, as well. In the absence of major poets and artistic movements, he had to develop his craft all on his own. Went through a long process of maturation — like me. Sees his particular artistic sensibility as having been created by homoerotic desire. Thinks that art depends on the experience of abandonment to the senses. That Eros is nourished by transient beauty, while Art makes beauty permanent. That Art imposes its will upon the art-object, removing it from the contingencies that dominate the natural and social worlds. That the alliance between nature and society is unholy. That to be free is to contravene laws and conventions, where these be natural or social or economic. And that this violation leads to a special kind of pleasure. That the pricelessness of “unnatural” love and its asociality, in that it doesn’t lead to marriage and procreation, links it to art, having no end outside of itself. Creation rather than procreation. That Art and Eros are benevolent deities, providentially controlling the destiny of those they have selected as worthy of their patronage. That loss is redeemed through the reanimation of the past, in the mind and body through memory, a capacity nurtured by solitary enclosure — enamored or trusted and dignified step by step, breath by breath, by city life — precluding the indifferent, eradicating void and uninspiring vastness of, for instance, sunsets.

In his late poems, some characters are depicted bearing the adversity, the unsparing, grinding power of history, with dignity and fortitude, courageously refusing to harbor comforting illusions. To me, Cavafy came late, maybe on the shelves of Prince Eisenherz, let’s say 1992 — and was beyond and beneath alien, unapproachable. I could not grasp, feel, relate, know, extract, gourmandize, instrumentalize, utilize — I couldn’t enjoy anything. Maybe in part because of my humanistic education — Latin and Ancient Greek, taught, I must say, by very good people in a hostile environment, completely erased my potential love for antiquity. Now, approaching old age, it comes as close to me as an embrace. Old age, maybe, is when you can become simply sensitive? Sensitively simple? With Cavafy it became, inadvertently, a love affair.

Thur, Sep 7, 2017, at 11:55 AM

Georges Seurat in Une Baignade, Asnières: Jonathan Crary considers this cherished painting still to adhere to notions of the central perspective, illuminating the fact that Seurat’s illumination is not mine, in that I don’t care about central perspective at all. Evoke the Gilles by Antoine Watteau and maybe you can talk about displacements, connected with vaporous hot weather, colors — I say vaporous, where Jonathan Crary speaks of a disrupted harmony created mathematically, or by a refraction of sound, light, and trouble.

Seurat’s thinking in a push and pull, there is no solidity at all. I tried all my best and that is the end.

Yours,

Lukas