A Blue Hand: The Beats in India

By Deborah Baker

Penguin, 2008

One has to wonder why we need another book on the Beats. Accounts of their lives and loves — and sometimes, of their works — range from the salacious to the cerebral. Many of these accounts have been by the Beats themselves. Prodigious and prolific, they wrote about themselves, they wrote about each other, and they wrote to and for each other. So what else could there be to say?

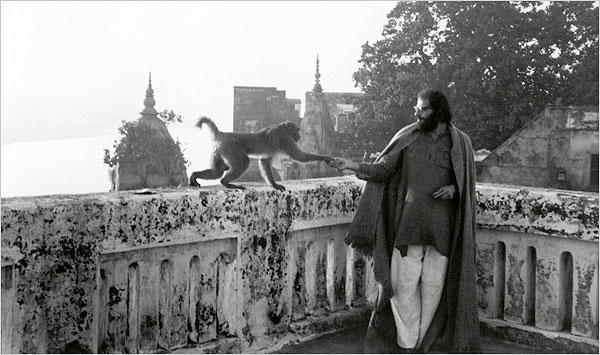

Deborah Baker’s A Blue Hand provides one answer: an account of the fifteen months that Beat-in-Chief Allen Ginsberg spent in India in 1961–62. This is not an untold story, exactly; for one, it was told by Ginsberg himself in a manically detailed yet sprawling jumble of writings — breathlessly lyrical and visceral records from his journal of what he saw and felt as he sought from the East answers that the West would or could not provide him. He also wrote letters, reams of them, to his father and family and, of course, to his fellow Beats: Gregory Corso, Lucien Carr, Jack Kerouac, and William S Burroughs.

Yet Baker does a remarkable job of telling her story. It is as if she is the mythical swan that separates milk from water as she dips into the hysterical treasure trove of text the Beats generated. Hers is a story of presences and absences — of Peter Orlovsky, Ginsberg’s off-again, on-again lover, who lived with him in Calcutta; of Gary Snyder and his wife, Joanne Kyger, poets on similar journeys; of Corso and Kerouac, who stayed behind; and perhaps even of Neal Cassady, with whom Ginsberg had been so hopelessly in love. Burroughs, whom Ginsberg had regarded as a spiritual guru as well as a literary mentor, figures especially prominently, especially by his absence.

(Ginsberg had had a spiritual epiphany in a Harlem apartment fifteen years earlier — a powerful aural experience of William Blake reciting his poem “Ah! Sunflower” — and his various journeys, physical and pharmacological, were efforts to recapture that moment of perfect intensity and veracity.)

The search for a new guru fueled Ginsberg’s magical, mystical tour through India. But perhaps the most compelling presence/absence in this book is that of the unlikely-named Hope Savage, a kind of muse or siren whose role in the lives of the Beats was so poetically apt that if she had not existed, someone might well have invented her. (I, for one, wondered whether someone had — there is scant information about her anywhere in the vast literary outpouring of the Beats, save between the covers of Baker’s book.) This elusive creature seems to have served as an evanescent metaphor for Ginsberg’s own quest for a truth that would liberate him. Though it was Corso who was desperately in love with her, in Baker’s account, Ginsberg, too, became obsessed with the girl called Hope as she appeared and disappeared, far away but so close, even as Ginsberg pursued a transfiguring life experience that was always just out of reach.

Baker also excavates the Bengali poets that Ginsberg spent so much time with in Calcutta, a city that had its share of madmen-mystics and seekers who were as dedicated to the idea of poetry as Ginsberg was. These are the pages that really come to life — not only because Calcutta was where Ginsberg had his deepest relationships with Indians, but also perhaps it is the city and the milieu that Baker herself knows best. In the rest of the book, India hardly appears at all, as we are constantly inside the poets’ heads, looking through their glass, darkly. Bombay was the hub of Indian poets writing in English at that time, but Ginsberg’s readings in that city are given short shrift, despite the fact that it was the “thin-lipped poet Nissim Ezekiel” (a great admirer of Beat poetry and a man profoundly moved by his own experiments with LSD) who persuaded Ginsberg to contribute his new poems to the Indian journal Quest that Ezekiel edited at the time, a contribution that affected the way Indian poets wrote in English for decades after.

Given that Ginsberg’s writings from this period form the bedrock of Baker’s work, and that they are entirely if not obsessively chronological therein, one might ask why Baker’s constructed narrative Christoph Keller Editions of those fifteen months from 1961 to 1963 (and a few short weeks in 1971) breaks in and out of linear time, dragging the reader to early twentieth-century Bengal and back, cutting and pasting, as Burroughs might have done, between letters and journeys that all occurred and were represented in linear time. The technique seems forced. But perhaps it was necessary after all — it lends A Blue Hand its uniqueness, and for such a well-traveled subject, that is no small achievement.