I am sitting in the sparsely furnished office of Lebanese architect Bernard Khoury. The only embellishment in the room comes from a large window, from which I can see a panoramic view of the city below. Opposite me sits a tired looking Khoury. He says he hasn’t slept much and needs to eat something. We go to a chic French restaurant called Balthus. In the past, Khoury has worked for its owner, creating the concept for the popular bar, aptly named because of its location, Central. At Balthus, we are given a rundown of the day’s specials. Behind us sits one of the most feared men in the city. Plates clatter, knives, spoons and forks jangle. Welcome to the new free Beirut.

Ten years after the end of the civil war, the former Paris of the Middle East has been given a make over. Maybe that’s too mild a description, some parts of the city look more like they have been surgically enhanced. This is down town Beirut where women frequently gloss their silicone-enhanced lips, restaurants and luxury shops shoot up like mushrooms, and stretch limousines wait in front of towering steel and glass buildings. Here, things that hark back to the city’s traumatic history have been bulldozed, all traces of battle erased. A new urban space has been created and the historical facades are restored with oriental motifs. The reconstruction firm Solidère was commissioned by the city to revive Beirut’s image. And some may think they have done well by creating this picture-perfect idyll. A quarter of a century of war has been masked over, all cracks and wrinkles smoothed, it looks like a city with repressed memories. But there are some who are fighting this, acting like psychologists who want to bring the trauma out of the psyche and into the open.

So you will find in some places that this new polished image has been rejected. An architectural maverick crept onto the stage and created a nightclub and two restaurants that stick out like sore thumbs. Bernard Khoury designed these buildings and they are like weeds in the otherwise immaculately manicured lawns of the new Beirut. Khoury has found his niche in post-war Beirut by creating uncomfortable architectural visions. He hacks away at the smooth surface created by the official reconstruction firm, and erects jagged and poignant structures. His buildings are marked by playful forms which hold a mirror up to the inhabitants of Beirut with brutal honesty. “Beirut is a hyper-contemporary end vision of a capitalist system which has spun out of control. There are huge social, economic and political contradictions and discrepancies between the meanings of culture, civilization and community. Despite the glamour, you are still subject to the foul-smelling scent of the city. However, I am fond of Beirut; it is an absurd reflection of Western societal development. Clean-cut and severe.” Bernard Khoury claims to be speeding up Beirut’s unequal development of power and wealth through his work, pushing it to its own breakdown, so that ultimately it will explode out of itself.

Khoury studied at the Rhode Island School of Design and did a Masters in Architectural Studies at Harvard University in 1993. He initially found it difficult to accept the system in Lebanon where, the architectural sector is not considered a cultural asset; rather it is subject to hard economic rules. “In Beirut I was forced to free myself from this custom. Every structure is an expressive force.”

And at no other time was this principal more apparent than during the construction of the B018 nightclub in the La Qarantina harbor district on the northern access highway to Beirut. The club sits on the grounds of a former Palestinian refugee camp whose inhabitants were massacred in December 1975 by Christian militias. The area was later leveled by an earthquake. It is, for the time being, home to the first alternative music club of the postwar period.

“At first it appeared to me completely out of the question to construct a building for a relatively frivolous purpose at such a location, instead of a memorial. But why can’t a restaurant, a shop or a club be an architectonic memorial? These so-called profane buildings in particular should be considered the true political reflections of society. This is an exciting area, as one is given the chance to work with norms and disruption.”

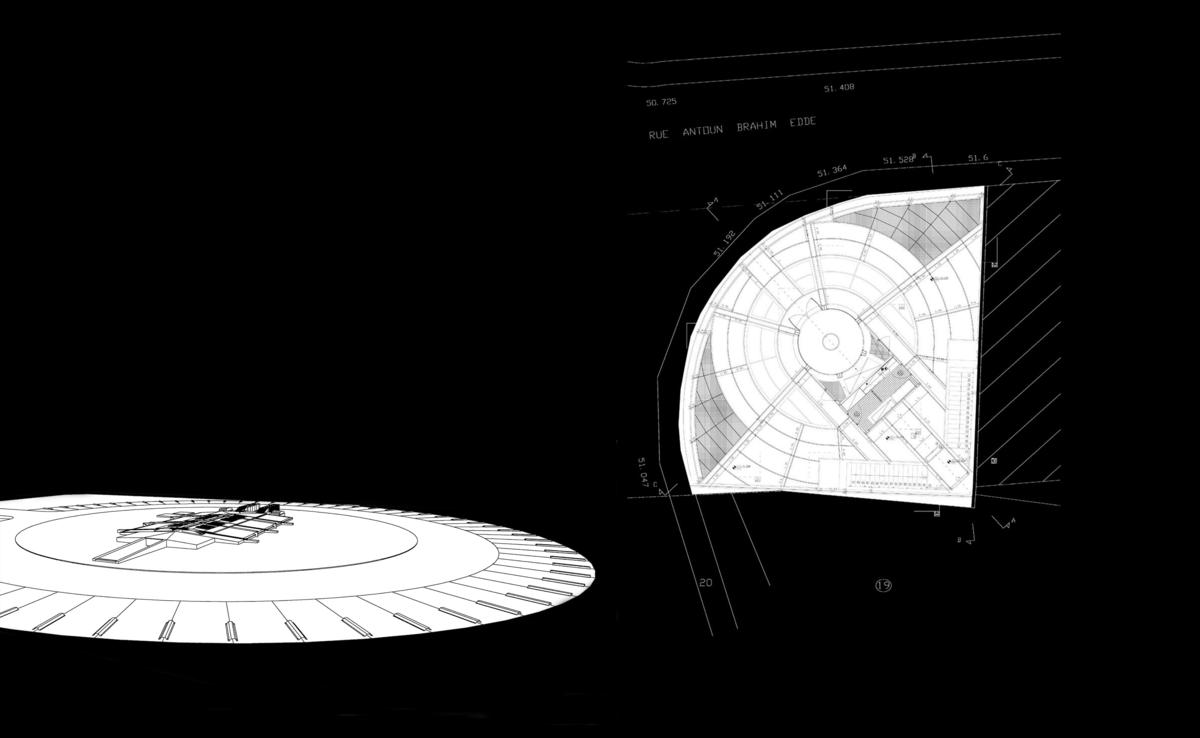

Khoury developed a concept free from moral categories. B018 sums up Beirut’s current sociocultural situation while at the same time confronting society with the past. The amusement temple is embedded deep within the earth. From the outside, the property is reminiscent of a missile silo. Guests approach in their limousines which are arranged according to size and “draped” dramatically in a semi-circle around the entrance. From that point on the irony of it all is thrust upon you.

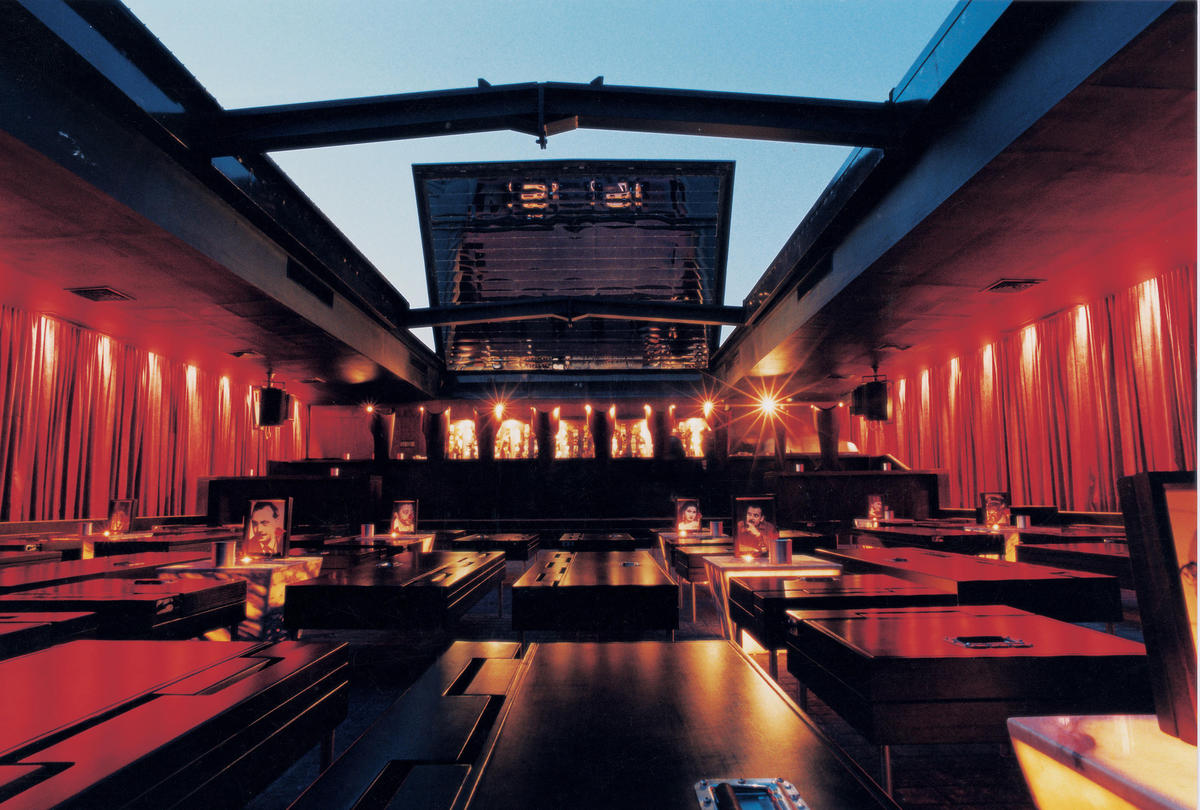

One enters the club by descending a bare flight of stairs, which leads the visitor layer by layer to the historical site of the refugee camp. The space has been given the form of a coffin — a single elongated room with a curved roof, which opens up via a mobile panel construction. The front wall of the room ends with a gigantic mirror over the bar, reflecting both the revelers inside and the city above. But the structure’s homage to death and remembrance doesn’t end there. Khoury’s tables are adorned with black and white photographs of dead singers and the seats are upholstered in morbid deep red velvet. Once folded together, they turn into miniature sarcophagi. But the appeal of this club doesn’t only lie in the design’s harsh reminder of the site’s past. Just as death comes knocking on our doors at some point, the grim reaper is already waiting in the wings for B018. The site was rented for a ten-year period. In 2004, the lease runs out, the club will be destroyed and become yet another part of La Qarantina’s history. But Khoury’s willingness to confront the past doesn’t end here.

A short drive from B018 one can find the gourmet sushi restaurant, Yabani. It sits on what was the Green Line, which during the war divided the Lebanese capital into East and West Beirut. It was the site of bloody battles between the various factions fighting for the city. Once again, Khoury felt that erecting a restaurant here seemed both vulgar and absurd. But he accepted the commission and just like his nightclub, this restaurant is situated underground.

A glass spot lit rotating elevator slowly carries patrons to the lower level. A video camera films their entrance, transmitting the images live to several television screens in the restaurant. The ride down ends in the middle of the dining area, the elevator shaft is surrounded by a bar. Those arriving get a good view of those dining and those dining can easily see whose arriving. Its effect is that of a showcase and one gets a feeling of being terribly exposed. The glossy up market sushi haven sits juxtaposed against its surroundings. On the street above pedestrians go about their business and the house next door is a bullet riddled shell which is home to several families.

Some may say it’s a provocation, but for whom? Khoury’s clients are the movers and shakers of the city. An elite group of people bent on creating a wonderland out of a war zone. But this architect doesn’t want to play by these rules. And so each project is a fine balance between pandering to their wants and maintaining his integrity. “We are playing with the needs of the upper class to dramatize their lives, but at the same time allow them to sense the absurdity of these desires. But flirting with the ‘noblesse’ [his clients] is like a constant tightrope walk. A game of temptation. I only accommodate them up to a certain point. That is my way of disrupting society. I am not cynical — rather I am frustrated. It’s useless to pretend to be an intellectual or an academic, or that one is working against the capitalist regime worldwide. Each one of us is a freeloader, when viewed from a critical perspective, as we can only exist if we tap into the system — we are only kidding ourselves if we say we’re independent. My work serves first and foremost the needs of the rich, but I try to subvert their impact. And at the same time, I undermine the foundation upon which I have built my constructions,” Khoury adds with a grin.

We are now at his office. Khoury stares into space for a moment and then suddenly his face takes on a serious expression. “This balancing act can be very frustrating, as I am constantly peering over an abyss. No one cares if I topple over — and when I fall, it will be a long drop.”