In which the editors collaborate with an artist to commission a newsroom graphic designer to visually render the report of the International Independent Investigation Commission Established Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 1595 (otherwise known as the Mehlis report).

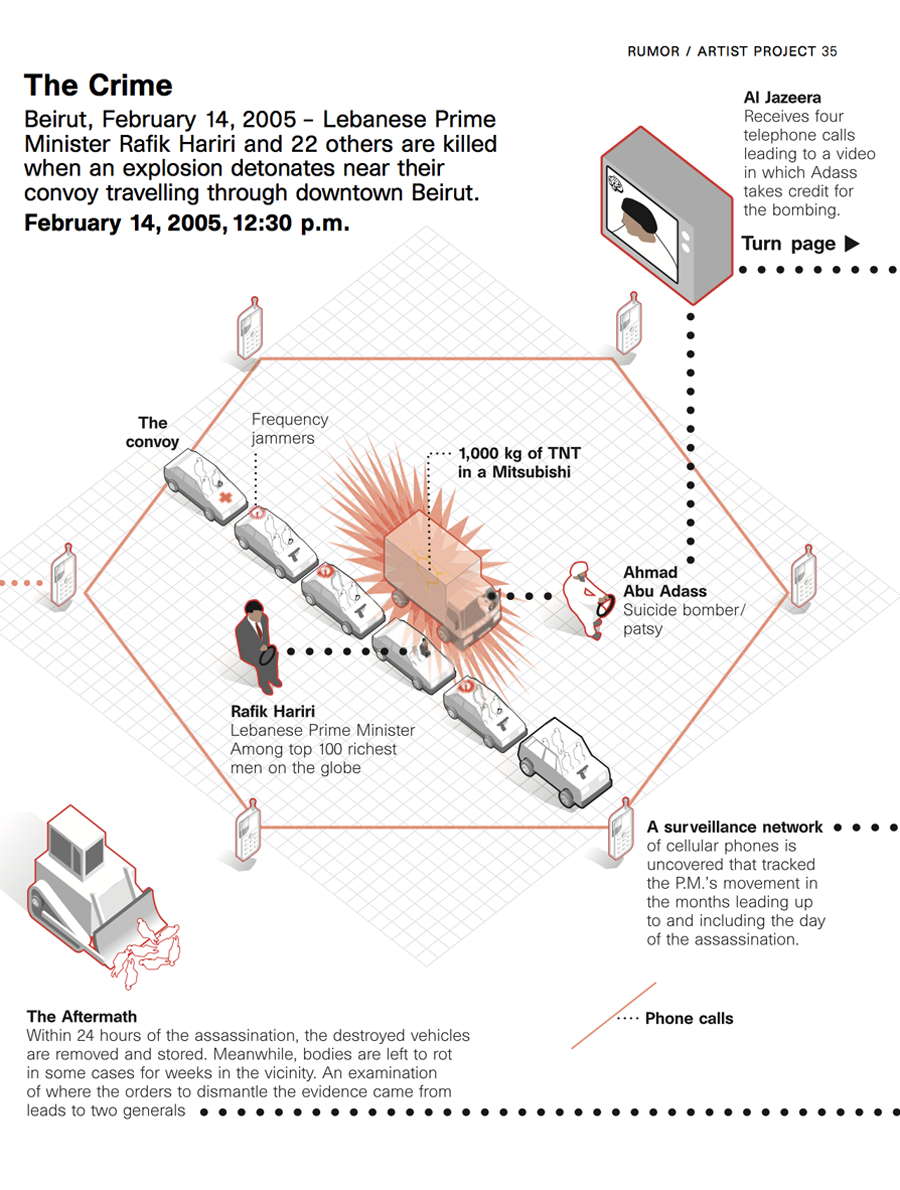

On February 14, 2005, explosives equivalent to 1000 kg of TNT were detonated as a motorcade made its way past the posh St George Hotel on the Beirut corniche, just steps away from the Mediterranean. The motorcade belonged to Rafik Hariri, a self-made billionaire who had served as his country’s prime minister from 1992 to 1998, and again from 2000 until his resignation in October 2004. Hariri, along with twenty-one others including his bodyguards and the former Minister of Economy, were all killed. In the hours and days following the assassination, there was no dearth of rumors circulating as to possible culprits, motives, final-minute scenarios.

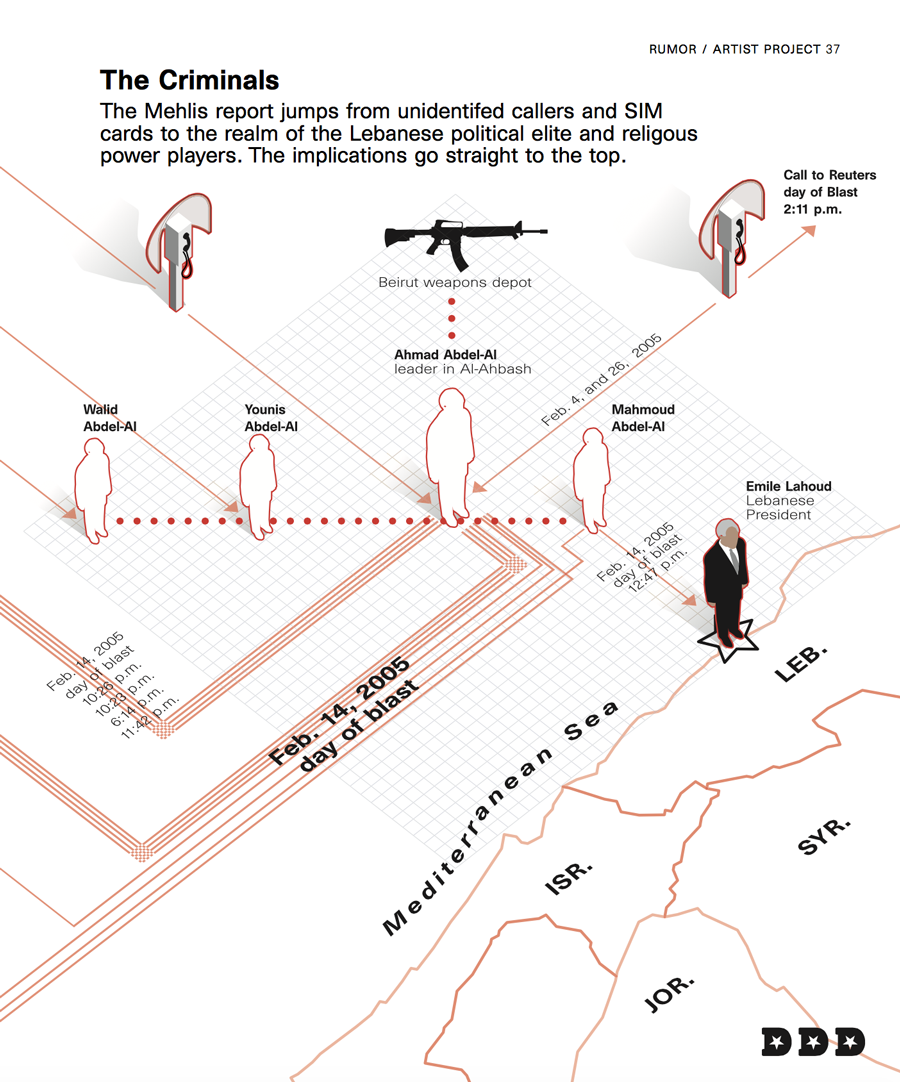

For some hours after Hariri’s death, the BBC speculated that the US or Israel may have in fact been to blame for the assassination. The Syrian foreign ministry echoed these sentiments. On July 4, 2005, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1595, establishing an independent international investigation of the former prime minister’s death. The team, headed by a German judge named Detlev Mehlis, presented its initial report to the Security Council on October 20, 2005. The Mehlis report implicated top Syrian and Lebanese officials, with special regard for Syria’s military intelligence chief, Assef Shawkat, as well as Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s brother-in-law. A second report, submitted December 10, 2005, upholds the conclusions from the first report. On January 11, 2006, Mehlis was replaced by the Belgian Serge Brammertz. In cities around the world, we have followed this investigation with great interest, anxiously awaiting the release of every UN report. We read the reports with a mixture of ambivalence, pleasure, and surprise. We responded, intrigued by their curious form, for these reports read like mystery thrillers.

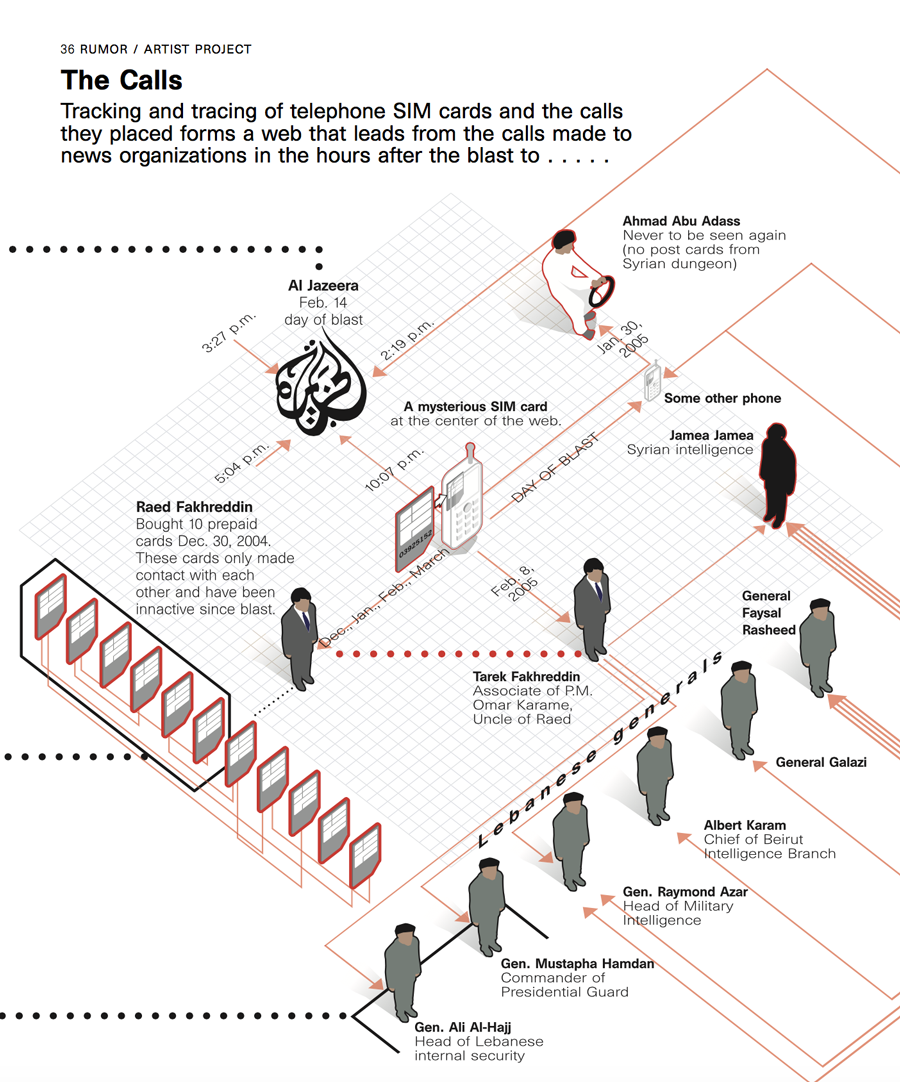

On the eve of the Lebanese government consenting to send the assassination to an international tribunal for further investigation, the editors and the artist referenced above commissioned a graphic designer from a major mainstream international newspaper to engage with the Mehlis report, to take on its presentation of time and place — with a focus on the chapter relating to the use of prepaid telephone calls made in the days and hours before the assassination (pages 57–58; sections 199–203). In the end, the SIM card, and prepaid phone cards generally, become the basis for linking almost every single one of the suspected players. Some links are direct, others are once-removed; and yet others are twice-removed. What is perhaps remarkable is the coincidence of all these individuals being linked to, for example, the prepaid card identified as 03925152 (section 200; page 58). In accepting this task, the designer was recreating the very act that takes place in newsrooms across the world, every day: that of reducing a complex set of facts and relationships into a consumable graphic form. We assume that the relationships charted here also formed the basis on which some players were ultimately arrested.

And perhaps it had to be this way; the resulting map was to be expected. We have anticipated that an artist or a designer somewhere would eventually visually map the information in the report. How could they not, given the currency of information-mapping in contemporary art, graphic design, financial, news, and meteorological reporting. In more ways than one, the visual map published here has been drafted numerous times, in pencil and ink, on napkins and notebooks, by readers of the report across the globe who sought to make sense of the facts, players, and connections listed in Mehlis (as the report came to be known in Beirut). Indeed, it seems as if the report’s published information encourages the kind of formal play evident in this seemingly-complete-yet-clearly-lacking diagram. This formal play parallels the kind of political play surrounding the entire Hariri investigation, in Lebanon, and in the United Nations. Connect the dots in a particular way, and you may blame the Syrian regime. Connect them another way, and you may blame Lebanese President Emile Lahoud. Connect them yet another way, and place the blame solely on the shoulders of the politico, Tarek Esmat Fakhreddine. There is no shortage of connections to be made here. As such, and as seasoned residents of Lebanon and Syria anticipated, the investigation has been reduced to signifiers that can easily become the anchors of any number of political stories.

What we come to know and how we come to know anything from Mehlis or from this published graphic remains a generative question. This is not to restate the obvious, namely that this on-going UN investigation was never about the truth but, rather, about politics. Surely, anyone who has scratched the surface of this assassination and its subsequent investigations has long ago concluded that juridical prosecution has taken a back seat to political prosecution. We need not revisit the interests of the major players (the United States, France, Iran, Syria, as well as proxy players in Lebanon such as Hezbollah, and the March 14 forces) as they have been jockeying for the past months in the UN for the most honorable and just position with regards to uncovering all of the facts related to the assassination, and to bringing all of those responsible for this crime to justice. It was clear then, and has become more clear since, that this investigation is one more negotiating card in the hands of the US and Europe in the on-going and far more present need to address Iran’s nuclear program, as well as Iran and Syria’s support of insurgents in Iraq. Given the limited investigative arsenal we can deploy to, for example, try to find out whether a particular SIM card was indeed tracking Hariri’s convoys, we must opt out of this game, lest we find ourselves in the face of a false choice: support an impartial investigation or politicize all findings and thus render any inquiry meaningless.

In this Part I, we chose to come close but also to move away from this diagram, for it can only draw us into the kind of game we are not equipped to play. The defense of this or that political player, of his or her juridical innocence and guilt cannot be our sole nor primary area of concern. This is not the urgent question par-excellence here. Or rather, this is not the urgent question par excellence for us. As such, and with this first, we have figured out what we do not want to pursue, a position we make clear by publishing this text along this fraught, incriminating map. Needless to say, we only hope that we may figure out soon what ought to be thought, produced, written, and stated. This is a long-term endeavor that will in part depend on the unfolding political and legal drama at hand.