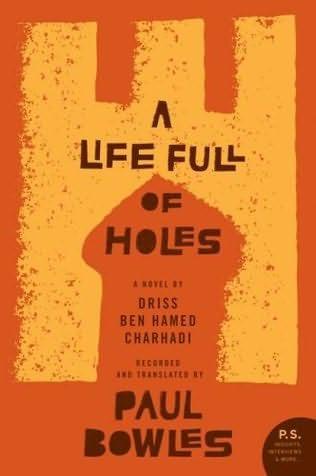

A Life Full of Holes

By Driss Ben Hamed Charhadi

Recorded and translated by Paul Bowles

HarperCollins, 1964

It is 1961 in Tangier, and “a singularly quiet and ungregarious North African Moslem” decides to go to the cinema. The bill includes an Egyptian historical film depicting the destruction of Cairo. Our protagonist emerges from the theater puzzled and on the way home stops in to see an acquaintance, the American novelist Paul Bowles. He wants to ask the writer whether it’s possible for such a great city to be destroyed without anybody hearing about it on the radio.

Bowles explains that the film is a fiction, a story. The man frowns; it is forbidden to lie. Bowles says, what about “The One-Thousand-and-One Nights;” we don’t call that lying. “That happened long ago, when the world was different,” he replies, shaking his head. “And books, like the books you write,” continues the man, who is completely illiterate, “they are all lies too?” Bowles insists: his books are stories, like the men from the countryside tell in the marketplace. “But then anybody would have the right to make a book,” the man says, half to himself.

Driss Ben Hamed Charhadi (as the man, Larbi Layachi, will be known to the world) telephones Bowles a few days later. “I’ve been thinking. I want to make a book, with the help of Allah. You could put it into your language and give it to the book factory in your country. Would that be allowed?” Everything is allowed, says Bowles, who is skeptical. Warning Charhadi that books are a lot of work, and reserving the right to reject the project, Bowles agrees to try a session with a tape recorder.

“After a long time he began to speak,” relates Bowles, in his indispensable introduction to A Life Full of Holes. “Immediately I knew that whatever the story might turn out to be, his manner of telling it left nothing to be desired. It was as if he had memorized the entire text and rehearsed the speaking of it for weeks… Nothing needed to be added, deleted or altered.” Over a series of sessions, and after recording two short stories, Charhadi began his great work.

Bildungsroman is too hopeful a word to describe A Life Full of Holes, which Bowles transcribed and translated from Maghrebi Arabic and promptly sold to Grove. The book recounts less a construction of identity than a systematic destruction of innocence, and the travails of its solitary narrator, Ahmed, leave Voltaire’s Candide looking like a Disney tale.

Ahmed begins life as a rather thickheaded child; at the age of eight, he spends months lost in Tétouan, because he can’t tell anyone his mother lives in Tangier. Once home, he’s unhappy, leaves, and spends days searching for a boarding school he’d loved briefly attending — but he never asks anyone for directions. He finally gives up on school and happiness and goes to work.

Working, not working, working: as a shepherd for a rich man, a money changer and a delivery boy, a street vendor, assistant to a baker, and a carpenter. Some better jobs, some worse, but nothing really good. Empty pockets, empty stomach, beatings, cheatings, days barefoot in the cold, and nights sleeping rough are routine.

Crime serves him no better. Ahmed pulls off one botched robbery. When he scores three kilos of kif in the mountains, his buyer in Tangier turns out to be an informer for the French-administered justice system and their brutal Moroccan cops. He joins a clumsy jailbreak from the Malabata Prison and stupidly remains in Tangier, sitting around in cafés with only a hooded djellaba to disguise him. He’s quickly returned to prison for a spell; then follows a heartbreaking love affair, nixed by the girl’s parents because he’s too poor. He goes back to prison.

Ahmed finally discovers the El Dorado of a certain class of hard-luck Tanjaoui: a gay Frenchman hires him as a houseboy. Male homosexuality has never been especially taboo here when performed on Nazarenes (the charming local term for foreigners, who all presumably worship the man from Nazareth), and Ahmed tells François, “Every man has a body to do what he likes with.” Ahmed’s work, decently paid for once, is in the house and the kitchen; the work in the bedroom is taken over by streetwise Omar, who feeds François the tongue of a dead donkey mixed into his food. This piece of mind-control witchcraft works perfectly — François gives Omar all of his money to get married and buy a house, and the Frenchman moves from his villa into a filthy shack nearby with another hustler. Soon they’ve drunk up the remaining money and stop paying Ahmed his pittance. When Ahmed complains, the Frenchman fires him, and Ahmed goes to sit in a cafe.

Ahmed’s tone is deceptive in its acquiescence. He observes the conventions common to poor Muslims, accepting that all of life is the will of God, including poverty and injustice. “Even a life full of holes, a life full of nothing but waiting, is better than no life at all,” Charhadi comments to Bowles, as they discuss a Maghrebi saying. This quietly fatalistic voice retains narrative heat while never boiling over into drama; Charhadi’s phrases have a rhythmic economy, which Bowles — a composer and musician before he was a writer — carries elegantly into English.

But as the rhythm of the story hammers away, the reader begins to sense Ahmed’s critical intelligence forming as a function of survival. A deliberate constant anger inoculates him against any self-pity. He becomes careful in his judgments, unequivocal in their expression, and fearless in acting upon them. The system may be shitting all over him, but there are no flies on Ahmed.

With the book’s English publication, Charhadi began to understand how radical his apparently straightforward storytelling really was. Ahmed speaks in terms of resignation; Charhadi’s flatly honest act of creation unleashed a savage indictment of social and political injustice in Morocco for any reader who knew another world. As the French edition from Gallimard in 1965 approached, Charhadi’s concern mounted about “possible official reaction” from the system he exposed. God forbids us to lie, but sometimes men forbid us to tell the truth. Bowles thought it best to procure him a visa for the U.S., and he left with William S. Burroughs on the transatlantic liner Independence, never to return. Larbi Layachi died in California in the late 1980s. But Charhadi would live on.

Some people’s Orientalism-detectors start beeping when they learn of the highly visible role of the Nazarene Bowles in the publication of dozens of books and stories composed by five Moroccan storytellers, including Mohamed Choukri, Ahmed Yacoubi, and Bowles’ friend and sidekick, the still-prolific Mohamed Mrabet. Clearly Bowles’s literary reputation, his own writing, and the many decades he spent living as Tangier’s favorite adopted son, were enriched by these collaborations. His translations were generally perceived as faithful (except for a contentious dustup with Choukri), and the translator tried to ensure his authors a fiftyfifty split of such money and publicity as he could extract from publishers. Perhaps it’s not his fault that with each passing edition, his name as translator tends to expand, relative to the authors’ names, on book covers.

Indeed, Bowles’s name is writ large on the front cover of this new HarperCollins release of Holes, while the back promises readers “a fascinating inside look at an unfamiliar culture.” If Charhadi could somehow be brought home to Northern Morocco to see this release, it’s a fair bet he would be unmoved by the type sizes and more struck by how little the city’s poor backstreets have changed in a halfcentury. This story — by a man who believed it was forbidden to lie — still hits with the clear ring of truth.