Abnaa Al Gebelawi

By Ibrahim Farghali

Al Ain, 2009

Arabic

In Ibrahim Farghali’s Abnaa al Gebelawi (Children of Gebelawi), all of the texts of the great Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz suddenly vanish from the face of the earth. This happens without reason or ostensible cause: wherever they might be found — not only in libraries and bookshops but also on shelves and bedside tables — novels by Mahfouz in their original Arabic are simply nowhere to be found. The authorities’ attempts to remedy the situation in the face of worldwide popular uproar are juxtaposed with sightings of Mahfouz’s characters in a variety of locales that seldom have anything to do with the settings in which they actually appear in Mahfouz’s books.

With seven books now to his name, Farghali (b. 1967) is among the most prolific novelists of his generation. In his devotion to the genre and his formal conservatism, he is perhaps the worthiest heir to Mahfouz (1911–2006), the Nobel Prize winner best known for his midcentury tales of Cairo. Unlike Mahfouz, however, Farghali is firmly steeped in a magical realist tradition. Running through much of his prose are echoes of José Saramago’s nightmarish humor and shades of Italo Calvino’s fascination with the fantastical possibilities of fiction. He’s taken with twins, telepathy, and teleporting, and his firmly middle-class characters — otherwise utterly ordinary — have been known to reappear after they’ve died.

In Farghali’s latest and greatest work, we face the prospect of a world without literature. The myriad voices in the book (our young narrator assumes many guises throughout these pages) express concern over the fraught future of Arabic literature, the erosion of the liberal and humane values that Mahfouz and his work represented, and (reflecting perhaps the essential fear of all writers) oblivion more generally.

The events of the book are staged around a relatively simple love affair between the narrator and the eccentric daughter of a well-to-do family — occasion for Farghali to probe the psychology of class and sex in contemporary Egyptian society. Further in, however, the story breaks up and morphs into countless alternative and subordinate plotlines, until it becomes clear (although it’s never stated) that the whole of Abnaa al Gebelawi is but the barely coherent product of a single pluralistic mind — the mind of a young writer concerned with the literary wasteland around him. The allegorical dimension remains predominant, and in this way recalls Mahfouz’s Awlad Haretnah (Children of the Alley, 1959), whose title in its English translation Farghali translated back literally for his own.

As it happens, Awlad Haretnah was the only book by Mahfouz to suffer censure from the religious establishment. In it, the history of a popular residential quarter in Cairo stands in for the sum total of humanity’s spiritual experience. That quarter’s oldest, strongest, and most benevolent resident — for many generations hidden away in his mansion — is called Gebelawi. Gebelawi has envoys or representatives, descendants or grandchildren, whose struggles to spread peace and justice make up episodes of the saga. Each episode is a retelling of the life of one of the prophets of Islam, starting with Adam and ending with the False Messiah. Moses, Jesus, and Mohammed all feature. At the end, a rumor spreads that Gebelawi himself has died. In Arab literary circles, it’s frequently claimed that if not for Awlad Haretnah, Mahfouz would not have received the Nobel Prize. But it proved too much for orthodox, let alone radical, Muslims, for whom Mahfouz would become the enemy soon enough.

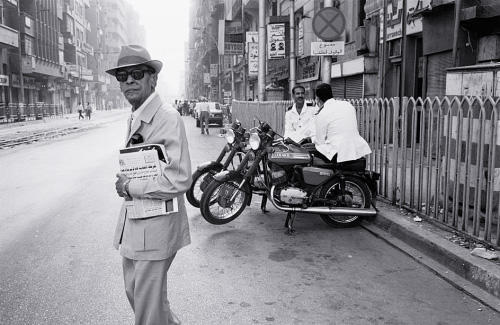

Radical Islam had claimed many lives since the 1980s when in 1994 Mahfouz barely survived being knifed outside his house in Cairo. The irony was that, of all the helpless octogenarians his bearded young assailants could have targeted for apostasy, he was probably the least secular. A typical Cairene of the pre–Bin Laden era, the man had led an all but exemplary (read, profoundly unadventurous) life. He did not seek revolution, he did not take great risks. He had no utopian or transcendental illusions. And perhaps it was thanks to this and this alone that he was able to invent and reinvent the novel, the youngest genre in the language, defining it for generations of Egyptian writers.

Applying every novelistic model at his disposal, Mahfouz produced a phenomenal number of readable books: social chronicles, political critiques, philosophical manuals. None was so difficult or experimental as to render it inaccessible to even the most common reader. Not one sought to undermine whatever pillar of the status quo it came in contact with. Notwithstanding the elaborately veiled, painstakingly respectful ages-of-man narrative in Awlad Haretnah — a Muslim treatise on the meaning of life, if ever there was one — in Mahfouz’s books, the family, the creed, the government, are never attacked for what they are or what they stand for, but only for their most striking deviations, omissions, or excesses.

For a magical realist like Farghali, Mahfouz may not be the most obvious point of departure; the Nobel laureate was, after all, devoted to the real even in his least realistic works, and one would have trouble imagining him so much as hinting at the paranormal or the fantastical. Yet in Abnaa al Gebelawi, the grand opera to Farghali’s various arias, Mahfouz’s books stand in for almost everything Farghali values: literature, thought, freedom, knowledge, love. The premise could not have been more powerful.