On May 14, 1964, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, flanked by Soviet Premier Nikita Kruschev, exploded a charge near the Nubian city of Aswan to inaugurate the construction of the Aswan High Dam. The dam, or El Saad el Aali, as it is known in Arabic, was a colossal public works project conceived by the architects of the 1952 revolution to usher the nascent Arab Republic of Egypt into the industrial age. They realized early on, however, that the dam would displace millions of gallons of water upon its completion, creating a massive reservoir that would submerge Nubia’s vast array of ancient monuments and leave the region’s native Nubian population homeless. For the tourist who visits Egyptian Nubia today, the High Dam, the salvaged temple of Abu Simbel and the Nubia Museum map an itinerary for a terrain inundated by displacements both literal and figurative. In the shifting of water, people, mountains and monuments, we can read the entangled representational legacies of colonial, national and universal claims to Egypt.

“We dug the Canal with our lives, our skulls, our bones, our blood, but instead of the Canal being dug for Egypt, Egypt became the property of the Canal! …Does history repeat itself? On the contrary! We shall build the High Dam and we shall regain our usurped rights!”1 Speaking in Alexandria in the wake of his nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956, Nasser imagined the proposed dam as a bulwark against western imperialism, a symbol of Egypt’s political and economic independence. In the national imagination, the High Dam became the very image of Egyptian modernity. Egyptian songstress Umm Kulthum, a singer so popular she was known as the Voice of Egypt, sang:

The Dam is no more a fantasy but an unprecedented fact. I gaze with overwhelming joy at an all-enlightening future with flourishing factories, and the color of green covering the arid land. Life of tranquility in abundance for all people and a pleasant journey to the top.

However, history shades this rosy popular vision of the dam to a darker tone. “The color of green” has been muddied by pervasive soil erosion downstream and the agglomeration of nutrient-rich sediment in the reservoir, the promise of “abundance for all people” is left unfulfilled given stark economic disparities between Egypt’s rich and poor. The prospect of “an all-enlightening future” is dimmed by the violent squelching of political opposition. Yet despite its actual economic, political and environmental legacy, the High Dam persists as a symbol of Egyptian progress, the first stop on its ever-imminent “journey to the top.”

For the tourist arriving at the dam by minibus, it is nearly impossible to escape some variation on the following observation by scholar William MacQuitty: “The dam itself rivals the pyramids, and will require fifty-six million cubic yards of materials, enough to build seventeen pyramids the size of Cheops’s great monument at Giza.”2 While the engineers of Egyptian modernity sought to end centuries of foreign rule and look to the future, the discourse of modern Egyptian monumentality is consistently articulated in terms of Egypt’s ancient past. Here, the modern dam is aggrandized at the expense of the diminished Great Pyramid, which is merely 1/17 the size of its modern counterpart. Moreover, in many accounts, modern monuments are inserted into ancient monumental discourse, a smuggling of the signs of modernity into the language of Egyptology that is so excessive that the future constantly threatens to spill over into the ancient past. Walter A. Fairservis writes:

A miracle is to happen in a truly antique land — a miracle that may in its way revive the glories of the pharaohs. For a great dam is being built on the borders of Nubia, ancient gateway to Africa, a dam that will dwarf all dams that seek to chain the waters of the Nile. Not since the Pleistocene have the mudladen waters of Africa’s mightiest river met such a barrier. Neither the granite-toothed cataracts nor the great desert cliffs of the Nubian plateau have offered the challenge to the river’s might that this new man-created, all-controlling High dam hurls at the water gods.3

What is to account for this displacement? What sort of Egypt could contain such a spectacle of ancient modernity? Perhaps Egypt’s investment in the modernity of the High Dam recapitulates western patrimonial claims on ancient Egypt. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, while the country was invaded by France and colonized by England, the vestiges of ancient Egypt were exported to Europe and systematically appropriated by the West as a part of its own patrimonial mirror. As Napoleon’s scholars and draftsmen completed the encyclopedic Description of Egypt, and as the halls of the British Museum were filled with plundered Egyptian artifacts, a particular image of Egypt formed in the heart of imperial Europe, one that was pumped out to its citizens in literature, museums, simulations and exhibitions. Egypt became the laboratory in which Europe fashioned a vision of its own eminence. European travelers to Egypt sought out not a “real” Egypt, but rather the Egypt of antiquity that was precisely imaged as a reflection of European progress. Western travel accounts from this period invariably either bemoan the Arabs and Turks who “clutter” their views of ancient monuments or denigrate them in order to aggrandize ancient Egypt and, by extension, their authors.

Investing modern Egypt with ancient monumental value renders Nasser and other Egyptian nationalists the inheritors of an imperial representational legacy. They sought to exclude the western presence from the High Dam by instrumentalizing the very means by which Arabs were excluded from the western picture of Egypt. And while Egyptian nationalist discourse was forged in the fire of anti-imperialism, it is resolutely hybrid, an alloy of colonial and national strategies for signifying progress. This desire to both break with the recent imperial past and appropriate the grandeur of an ancient one attests to the complexity of monumentality in modern Egypt. With the waters of Lake Nasser threatening to rise in the 1960s, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) spearheaded an international effort to salvage Nubia’s monumental heritage. Abu Simbel quickly became an object of international appropriation under the aegis of universal world heritage. The entire structure, from the four enormous colossi of Ramses II that form the facade to the colonnaded antechamber to the inner sanctuary, is carved from a mountain that sits on a remote bank of the Nile. In fact, the orientation of the structure, which dates to 1270 BC, is so precise that it is only at sunrise on two days of the year — February 23 and October 23 — that a ray of light penetrates the innermost sanctuary of the temple, illuminating three of the four deities seated inside and leaving Ptah, the god of darkness, in the shadows.

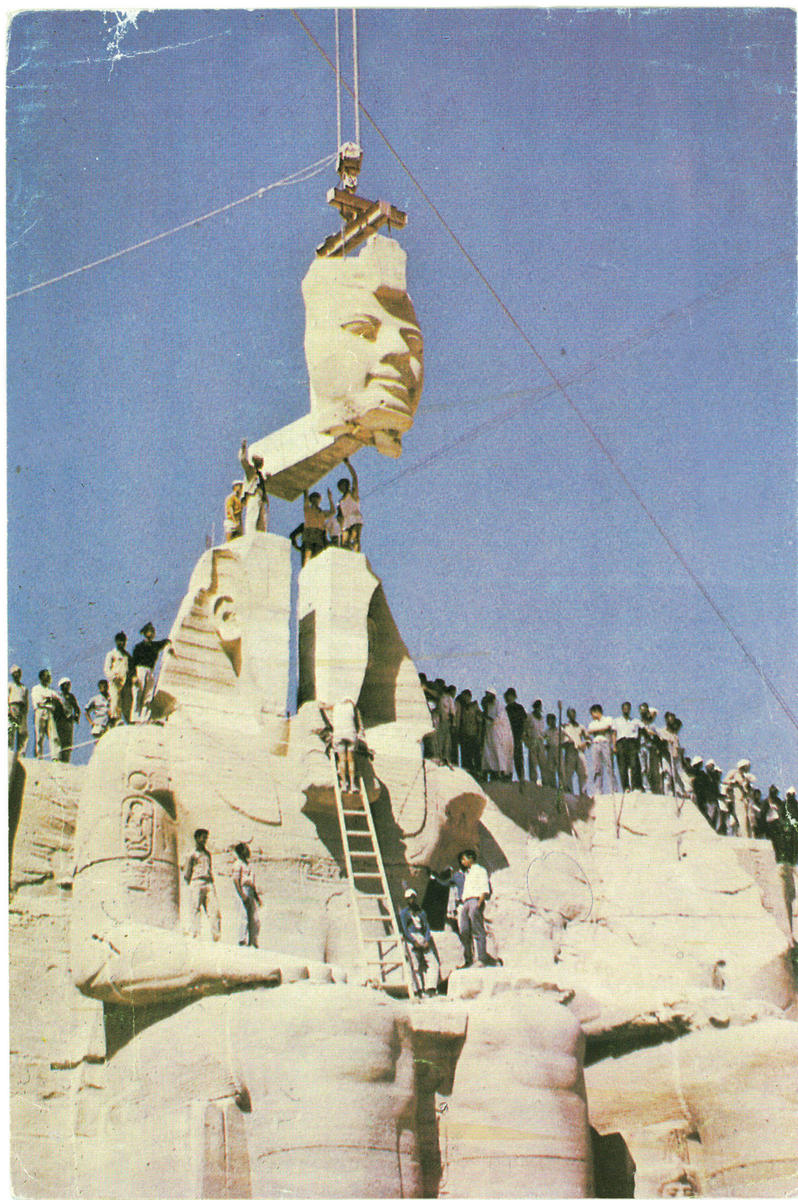

When faced with the challenge of preserving such a site-specific monument, UNESCO elicited proposals from member states around the world, proposals that ranged from the practical (the creation of another coffer dam protecting the temple) to the absurd (jacking up of the entire mountain and filling its underside with massive inflatable balloons on which the entire temple would float) to the fantastic (surrounding the temple with a filtration dam that would permit only pure water and chemical agents to strengthen the rock and building glass elevators for tourists to navigate the underwater temple). What was eventually agreed upon was the so-called “Humpty-Dumpty Scheme,” in which the entire mountain, temple and all, was carved up into twenty-ton blocks that were assembled and fit into a concrete dome disguised as a natural hill at a site sixty-five meters higher.

At the ceremony to mark the completion of the preservation in 1968, René Maheu, Director-General of UNESCO, addressed Ramses II directly:

Using means unimaginable to you, but ever mindful of your intentions and your rites, we cut away the mountain, hewed in pieces the statues, pillars, and walls hidden beneath the earth, and then rebuilt in the light what you had hollowed out of the darkness and raised over it the strongest protecting dome ever built by the hand of man. The dome we covered with the very rocks in which you had built your mysteries.4

By directly addressing the pharaoh, Maheu razed the dam between ancient and modern monumental discourse. No effort was made to sanitize the displaced monument, render it more authentically ancient, or repress its elaborate simulation. In fact, the dome is an integral part of the guided tour. After a walk through the temple, one is led through an inconspicuous doorway off to the side of the facade and swallowed by the yawning mouth of the concrete dome rising sixty feet above. Faced with the ghostly presence of the temple cast in concrete, one’s fragile belief in the spectacle unravels like the denouement of a Hollywood mummy movie. But Abu Simbel is more like Frankenstein, a hybrid of ancient monument, modern spectacle, and postmodern simulation, cobbled together and animated by the proliferation of claims on Egypt. The dome does not inspire; instead, one sees the place in its fullness, as a modern supplement to a strange tour of Egyptian identity.

The late Edward Said wrote in a 2002 essay, “everyone who has ever been to Egypt or, without actually going there, has thought about it somewhat is immediately struck by its coherence, its unmistakable identity, its powerful unified presence. All sorts of reasons have been put forward for Egypt’s millennial integrity, but they can all be characterized as aspects of the battle to represent Egypt.”5 Put your ear to the cracks that persist in fragmenting Abu Simbel and you can still hear the echoes of this battle — from the explosion that consummated Egypt’s marriage to the project of modernity to the scream of the first drill that pierced Abu Simbel’s sandstone surface, to this account of the completion of the temple’s reassembly: “It was an unforgettable event, and a moment of triumph for all those who had fought for the cutting scheme.The only persons unmoved, at least visibly, were some Nubian workers clinging to the immense legs of the God-King, filling the joints of the blocks.”6 In the Nubia Museum, close to Aswan, one can find these Nubians, unmoved still, in the frozen dioramas that simulate the manners and customs of a people displaced by the waters of Lake Nasser. Tourists can find the real Nubians resettled in villages manufactured by the Egyptian government or in the halls of the Nubia Museum itself, giving tours of a culture that has been mummified alive alongside the pets of the pharaohs. Here, they work to fill in the cracks that attest to the price of modernity, dissimulating the violence of how this coherent Egypt was indeed put together.

1 Al-Ahram, July 27, 1956.

2 William MacQuitty, Abu Simbel (London: Macdonald, 1965) 141.

3 Walter A. Fairservis, The Ancient Kingdoms of the Nile and the Doomed Monuments of Nubia (New York: Crowell, 1962) 2.

4 René Maheau, “Abu Simbel: Address delivered at the ceremony to mark the completion of the operations for saving the two temples” (Paris: UNESCO, 1968) 35-36.

5 Edward Said, “Egyptian Rites” in Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2002) 154-5.

6 Temples and Tombs of Ancient Nubia: The International Rescue Campaign at Abu Simbel, Philae and Other Sites, ed Torgny Säve-Söderbergh (London: Thames and Hudson, 1987) 121.