Two Clarkes walk onto the roof of the Chelsea Hotel with a laser: it sounds like the start of a bad joke, and in a sense it was: a cosmic joke, a stoned prank, a sad story, really, with not many laughs. But if you’re looking for laughter, Shirley and Arthur on the roof with the laser beam may be your last chance.

Shirley Clarke was an indie film auteur and video trickster who ran something called the TeePee Video Space Troupe out of her home at the Chelsea, a trial run for what she called “the Pleasure Palace Theaters of the Future,” labyrinthine multimedia spaces that would be both liberated and liberating. The Chelsea Hotel was the prototype: the whole building was wired. The Troupe’s preferred medium was video, but they didn’t make tapes. They held rituals, live, in front of flickering effigies made of video monitors as dawn broke over the city; they communed in the pyramidal structure that Shirley called the TeePee, and spread out through the elevators and hallways, intent on Rimbauldian derangements of the senses.

It wasn’t the kind of scene that left very much behind, anything except stories, like the night the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke showed up at the TeePee with a long rectangular box containing a laser beam projector loaned to him by a techie fan of 2001: A Space Odyssey. “Shirley and Arthur giggled like kids phoning in bogus pizza orders,” DeeDee Halleck, a Trouper and media activist who went on to found Paper Tiger Television, remembers. Arthur was an irregular but welcome presence at Shirley’s rooftop salon-cum-laboratory, which convened more or less continuously from 1971 to 1975; video held a utopian appeal for him, too, as a herald of the new technological epoch just around the corner, along with orbital satellites, robots, and manned spaceships. At the Chelsea, the technofuturist and the performance-art prankster came together — not for the first time — to bedevil the man and woman on the street. Passersby kept trying to pick up the bright red object on the ground, and “both Clarkes roared with laughter as they made it jump five feet out of reach.”

But it would never have happened without Shridhar.

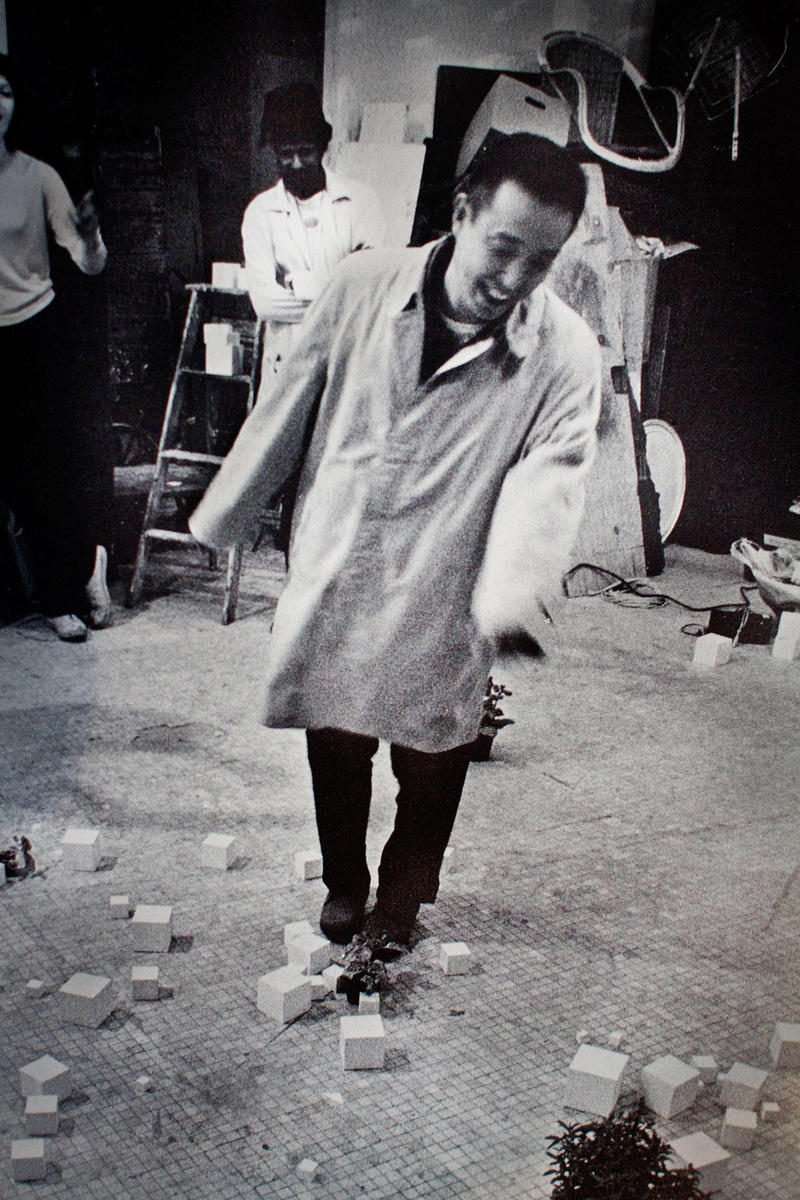

This first-generation laser pointer was too bulky, too heavy, to be wielded by hand, particularly the hands of the TeePee’s regulars. Shridhar improvised a mount out of a tripod, then fixed the tripod to the roof ’s edge, allowing the laser beam to swing freely according to the whims of the Clarkes. Shridhar Bapat was Shirley’s assistant, the tech guy at the pleasure palace; he’d joined the Troupe after leaving The Kitchen, where his official position was Director (if you believe the paperwork) and unofficial position was factotum and dogsbody. He was an expert at managing what they used to call Spaghetti City — the mess of wires that connected cameras to monitors, early video synthesizers and recorders, tape to reel. It wasn’t easy in the first place, and almost everyone was stoned, anyway. But Shridhar could keep the video cameras from jamming, the tapes from spooling off the open reels; he could rig up monitors and cameras into complex machines for the production of video feedback.

Even Shirley Clarke is almost forgotten now, and Shridhar doubly so, way more than five feet out of reach. But back then he was always there, behind the scenes, making things work. John Hanhardt, senior curator for media arts at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, put it to me like this: “He was a major player. How many people have worked with the range of artists he worked with?” Nam June Paik’s tremendous grasp of television’s potential as an art medium required technically adept assistants like Shridhar, who worked for him off-and-on for a decade. He helped Shirley Clarke realize her most far-fetched ideas — and Woody and Steina Vasulka, and Al Robbins, and every other major videographer east of the Mississippi. Sound artist Liz Phillips, whose first show at The Kitchen included a complex multimedia piece called “TV Dinner,” remembers that Shridhar made it possible. “He was really, really good. Before I knew it he was taking the image from the table and bouncing it all over the room. He had the sense of how to take what we were doing and turn it into a viable installation.”

He could even manage just fine when he was drunk.

1. The Aleph

I am a cybernetic guerilla fighting perceptual imperialism… VT is not TV. Video tape is TV flipped into itself… [Tape is metatheater…] Tape is feedback.

— Chloe Aaron, “The Video Underground,” Art in America May/June 1971

People remember Shridhar Bapat fondly because they remember themselves fondly, remember those years fondly, when the first flowers of the videotape underground bloomed in the smoky air of Lower Manhattan, in burnt-out basements and moldering once-grand hotels, in unheated lofts and screening rooms. They were by turns infantile, mind-bending, self-obsessed and eerily prescient, a motley tribe of longhairs and losers, communitarians and Uptown-gallery poseurs, attended by a coterie of tech-heads armed with duct tape, Q-tips, and obscure expertise acquired the hard way. And they were busy: recording hipsters and their sidewalk raps and Hells Angels chopping their bikes before a big ride; Panthers brooding and women’s libbers on the march; fabulously furry freaks fucking, stoned, on quilts, illuminated by the strobing low-fi emissions of a wall of TV sets. But the recording wasn’t the point, not yet; they thought they were laying the foundations for a better global village, peopled by citizen-transmitters and citizen-receivers. In the new “media ecology,” the art world would soon cease to exist, along with the banking system, broadcast television, rent, antiperspirant, and the military-industrial complex.

The revolutionary weapon that made all of this possible was the Sony Portapak, a Japanese invention that arrived on American shores in 1967. Eleven hundred dollars would get you a bulky open-reel videotape recorder, a separate camera unit with a built-in mic, a battery pack, and a power adapter. A twenty-minute reel of tape set you back fifteen bucks — and unlike film, required no further developing or processing. It could be played back right away, or you could just erase it and start over. With the Portapak, suddenly the first generation raised on broadcast television had acquired the means to create stations of their own.

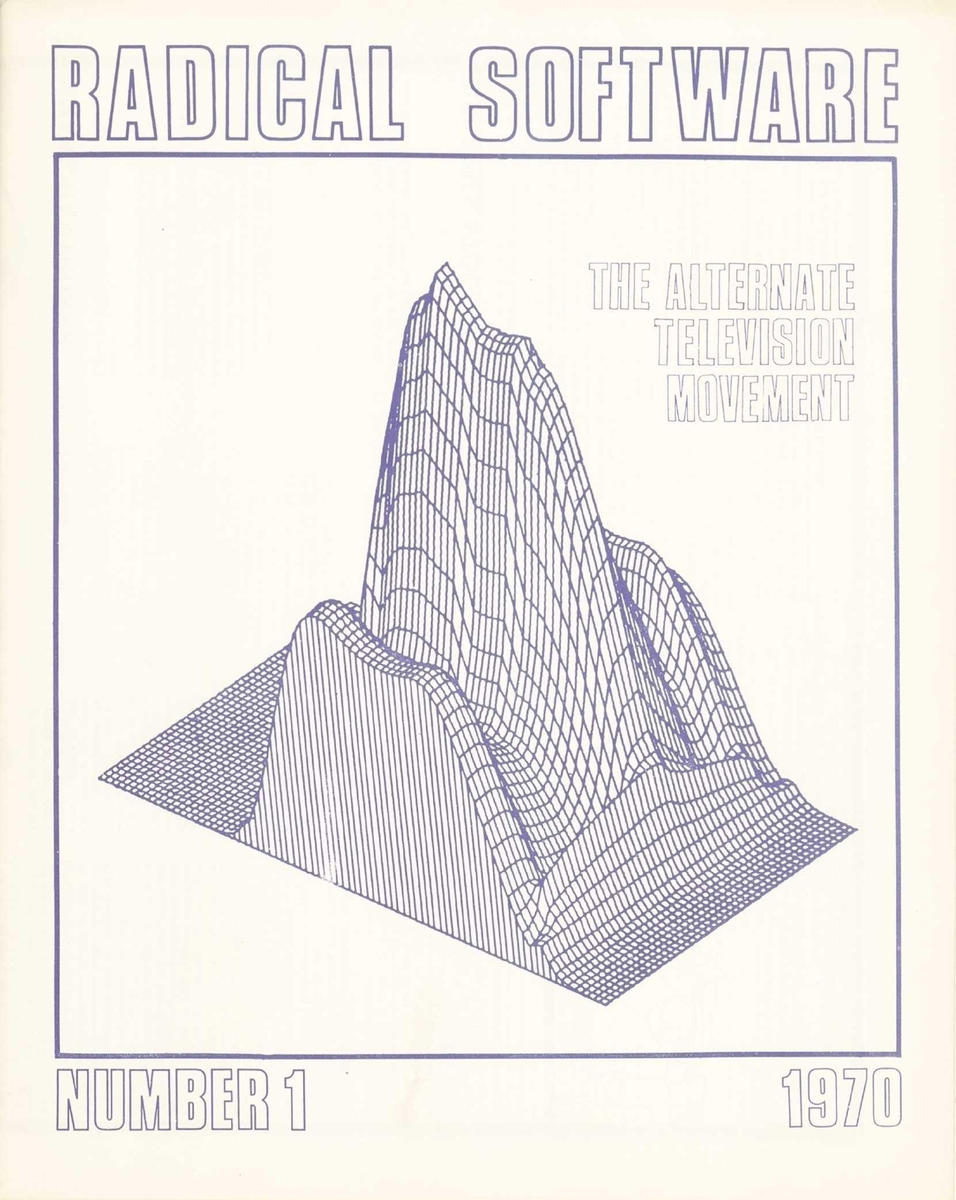

For Shridhar and for scores of others, this medium that barely existed became a way of life. He’d learned the basics of video at the New School, in a class taught by Global Village, the first of the city’s video collectives. Its name derived from Marshall McLuhan, whose thinking about media and consciousness made an outsized impression on the video scene, and who’d arrived in New York in 1967 to teach at Fordham University. His students included Paul Ryan, cofounder of another collective, the Raindance Corporation (a riff on the RAND Corporation, itself an acronym for Research ANd Development), and its offshoot journal Radical Software. A third group that called itself Videofreex would go on to launch the world’s first pirate TV station. By 1971, videotapes, including Shridhar’s, were being shown at the Whitney and at The (brand-new) Kitchen, and the number of videotape auteurs went from dozens to thousands. Collectives and alternative distribution systems, ’zines and screening rooms, sprang up across the globe.

It was a milieu in which the old media seemed exhausted, wrung dry after two decades of successive -isms and movements. In the first edition of the influential Video Art: An Anthology, published in 1976, Hermine Freed described how video had arrived “just when pure formalism had run its course; just when it became politically embarrassing to make objects, but ludicrous to make nothing; just when many artists were doing performance works but had nowhere to perform, or felt the need to keep a record of their performances.” At a time when the status of the art object was an open question as never before, the process-orientation and the immediacy of the low-fi videotape felt like the answer.

But the immediate target of the early video activists wasn’t the art gallery or the museum — it was the mass media, especially television. In his influential Expanded Cinema, first published in 1970, Buckminster Fuller acolyte Gene Youngblood called television “a powerful extension of man’s central nervous system. Just as the human nervous system is the analogue of the brain, television in symbiosis with the computer becomes the analogue of the total brain of world man.” The new age, the cybernetic age, would combine “the primitive potential associated with Paleolithic” with the “transcendental integrities” of the Cybernetic, producing a new man, an ideal figure whom Youngblood envisaged as “a hairy, buckskinned, barefooted atomic physicist with a brain full of mescaline and logarithms, working out the heuristics of computer-generated holograms or krypton laser interferometry. It’s the dawn of man: for the first time in history we’ll soon be free enough to discover who we are.” Gnostic truth and feedback loops: the visual analogue of the sound of Hendrix at Woodstock was the tripped-out pattern made by a camera turned back in on itself. Woody Vasulka says that when he first saw video feedback, “I knew I had seen the cave fire.”

Early video exploited video feedback both as a tool for creating utopian communications systems and as a source for psychedelic pattern-making. In the most influential early multi-monitor video installations, you could watch yourself watching yourself; cameras could be pointed at each other, at monitors, generating pure electronic signals in the tube, a videospace pulsing with feedback’s overflow and excess. This was Shridhar’s element. He boasted to his friend Bob Harris that he was “the best feedback camera turner” in New York. A night watching — or making — videotapes with Shridhar was a trip to the other side. The titles in a handbill advertising a “video mix” by Shridhar Bapat at The Kitchen in 1971 hint at the cocktail of noisy electronic abstraction and metaphysics that intrepid viewers could expect to take in:

Om

Serendipity

R.f.

House of the Horizontal Synch

Star Drive

Shridhar’s early videotapes are invisible now, like so much else, the only copies sequestered, unseen and unseeable in Northwestern University’s Special Collections. (Early videotapes are extremely fragile; the policy at many collections, including Northwestern’s, is that a tape cannot be screened even once until it is digitized.) The one I’d love to see is Aleph Null, a tape inspired, I take it, by Jorge Luis Borges’s 1945 short story “El Aleph.” Shridhar, for all his love of the image, was rarely seen without a book.

“El Aleph” is the story of a writer — also named Borges — who finds himself flat on his back in a cramped Buenos Aires cellar, staring into the darkness and contemplating whether his nemesis, the fatuous poet Carlos Argentino Daneri, might have buried him alive to prevent him from disclosing the madness at the heart of Daneri’s megalomaniacal project: a complete description of the world and everything in it, in verse. Daneri lured him there with talk of an otherworldly object, part secret weapon, part muse: an Aleph, “the only place on earth where all places are — seen from every angle, each standing clear, without any confusion or blending.” As Borges lies in a panic, convinced of his doom, the Aleph suddenly appears to him, and what it reveals seems very much like the realization of video’s spectacular promises:

I saw a small iridescent sphere of almost unbearable brilliance. At first I thought it was revolving; then I realized that this movement was an illusion created by the dizzying world it bounded. The Aleph’s diameter was probably little more than an inch, but all space was there, actual and undiminished. Each thing (a mirror’s face, let us say) was infinite things, since I distinctly saw it from every angle of the universe.

Overwhelmed by the desire to describe the endless simultaneity before him — this infinite, recursive net of self-reflecting mirrors — Borges’s sense of time and space collapse, abandoning him to a mock-epic catalog of things, a spaghetti city of words, the ranting of a subterranean, self-loathing Whitman manqué. At last the Aleph’s technological sublime blows his mind like a four-faced God in heavy, holy spate:

I saw the Aleph from every point and angle, and in the Aleph I saw the earth and in the earth the Aleph and in the Aleph the earth; I saw my own face and my own bowels; I saw your face; and I felt dizzy and wept, for my eyes had seen that secret and conjectured object whose name is common to all men but which no man has looked upon — the unimaginable universe.

I felt infinite wonder, infinite pity.

2. Infinite Wonder

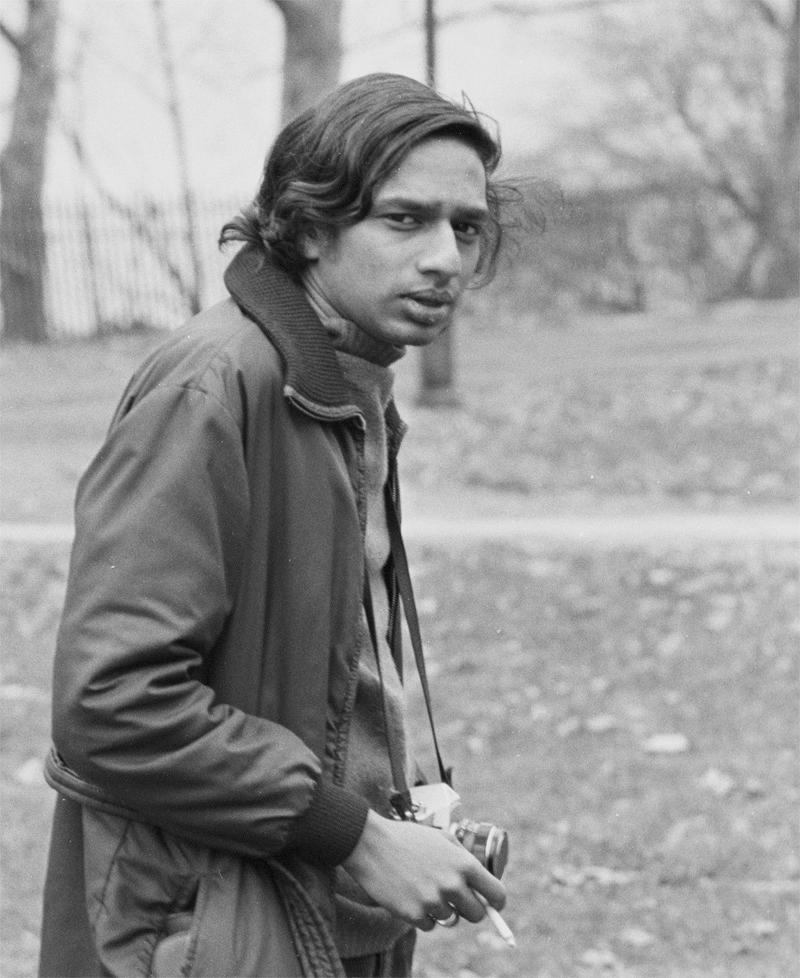

“He was the first and only salaried person at The Kitchen,” Steina Vasulka told me. She spoke to me on a video chat from the home she shares with her husband Woody Vasulka in New Mexico, remembering The Kitchen’s earliest days, from 1971 to 1973, when it was still located in the former kitchen of the Broadway Central Hotel, in the Mercer Arts Center. “He had hair that I thought was too long. He had these eyes, this dark brown color, and kind of a beautiful, interesting face. A very low voice that he never raised.”

At one point some French video artists came wanting to do a show at The Kitchen but they spoke only French. “Shridhar was there working in the back in his quiet way. He came out and said, ‘Maybe I can help.’ That was how we found out that he went to the finest schools in Switzerland… this tiny Brahmin who spoke perfect French.” The trajectory that had brought Shridhar to the new medium was unique, but so was most everybody’s. Steina and Woody Vasulka had come to New York from Iceland and what is now the Czech Republic, respectively; Shigeko Kubota from Japan; Nam June Paik from Seoul via Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Darmstadt. Their milieu — the whole New York avant-garde at the time, really — was full of outsiders and expatriates.

Shridhar’s journey had begun in India, sometime around 1948. He may not have been one of Rushdie’s “midnight children,” born during Nehru’s famous speech marking India’s independence from Britain at the stroke of midnight, August 14, 1947, but Shridhar was definitely a child of the morning after. His father, Shriram C. Bapat, was a high-ranking diplomat in Nehru’s government, and the family left India for Japan as part of a UN delegation sent to assess the long-term effects of the atomic bomb. Shridhar was two. Soon thereafter they moved to New York, where his father was a key member of India’s delegation to the UN. Shridhar spent most of his childhood in suburban Westchester. He was a small, slight kid who liked to play in the parks, learning to speak with what his high-school friend Bob Lewis called a “New York cadence” — a boy invested with all the bright prospects of an elite Indian family, swimming at the high-water mark of an optimistic age.

His Westchester idyll came to an end in 1962 when his father was transferred to Ghana. They sent Shridhar to Geneva, to the bilingual Ecole Internationale du Genève. Better known as Ecolint, it is the oldest operating “international school” in the world, a deeply cosmopolitan institution with students from across the globe, many of them from diplomatic families like the Bapats. Nehru’s own daughter, the future Prime Minister of India Indira Gandhi, had attended Ecolint for a year in 1926.

Shridhar graduated from Ecolint in 1968. According to his yearbook page, Shridhar Bapat, India (“not one for apathy”) had risen to the rank of Head Monitor (“that Indian guy”), Intern Senior Prefect, President of the Finance Committee, United States delegate to the school’s model UN, chairman of the Political Seminar, Bridge Club member; a student whose “fond souvenir” consisted of “growing up in L’internat, Genève.” A handwritten note on Bob Lewis’s yearbook reads: “Louieee: Zo, ve haf reached the end of the Ecolint milk run. As I go out into the big bad world, leaving behind me this womb to beat all wombs, I wish you success in whatever you end up doing. Fate, mystical inner knowledge et al. Ciao.” Shridar’s plans were twofold: “University in England; Career in govt.; to plumb the depths of human conceit.” With hindsight, we might say he got it about half right.

1968 was either a great year to arrive at the London School of Economics or a terrible one, depending on your ambitions. It was a hotbed for highly factionalized ultra-Left politics: fired up by the antiwar protest-turned-riot in front of the American embassy on Grosvenor Square in March of that year, stoked by Paris’s revolutionary month of May, and abetted by charismatic student leaders like Tariq Ali and radical chic icons like Vanessa Redgrave, some three thousand students at the LSE occupied its administration buildings in October of that year. When the dust finally settled, many were expelled, Shridhar among them. From London he made it back to New York and somehow found his way downtown, quickly becoming the quintessential video scenester.

I first encountered Shridhar’s name while looking through archived documents from The Kitchen’s earliest days for traces of another of New York’s avant-garde Indians, Pandit Pran Nath. “Shridhar Bapat” was listed everywhere, as director of video programming, as program director, as curator. Seeing him there next to names that were famous (or at least, recognizable), I wondered who he was and why I had never heard of him. I thought at first that it might have been some kind of prank, a “Mahatma Kane Jeeves” buried in the paperwork. But I asked around, and before long my inbox was inundated with emails, solicited and not, from artists and TV people, public-access activists and professors, all of whom wanted me to know something about Shridhar.

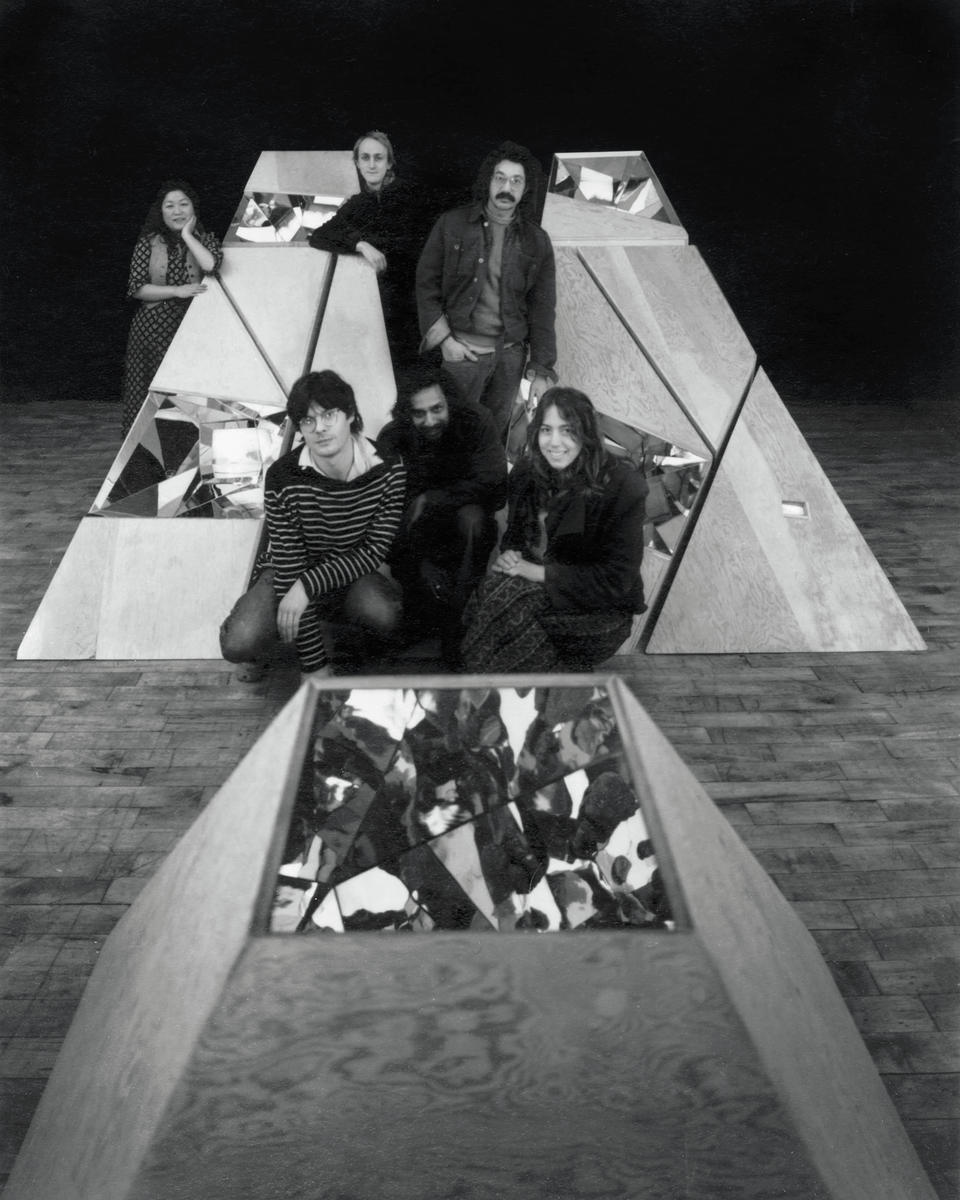

I spent the next year interviewing dozens of them. But even then, his story was full of holes — lies, too — and it ended in the biggest, blackest hole of them all. His history was itself a kind of cipher, an almost imperceptible gap in the now-accepted narrative of video history, one that opened up onto an alternate recension of that history. Last year, when The Kitchen celebrated its fortieth anniversary with The View from a Volcano, an exhibition of artifacts and photographs documenting its development, Shridhar appeared just once, a small face in a group shot on a wall near the door, hardly visible amid all the famous lava bombs going off in the other parts of the room.

His years at The Kitchen were the high point of Shridhar’s professional life. He was part of the first generation there in 1971, along with his friend Susan Milano, another young long-hair named Dimitri Devyatkin, and Rhys Chatham, the seventeen-year-old director of music programming. Video artist Shalom Gorewitz, who wrote a monthly column about video for a magazine called Changes in the Arts and was at The Kitchen “practically every night” in those days, saw Shridhar “as the glue that held all the things there together.” When he was there, Shalom told me, things ran smoothly; when he was not, things fell apart.

He was a highly effective curator — though in those days they disdained the term, with its exclusivist connotations. With Milano he organized the first Women’s Video Festival at The Kitchen in 1972. Many of video’s earliest and most enthusiastic adopters were artists associated with the feminist movement. (By Steina Vasulka’s estimate at least a third of the people making video in the early seventies in New York were women.) It’s no small measure of Shridhar’s diplomatic instincts that he was intimately involved in creating a visionary feminist institution at a moment when the culture wars around women’s rights were erupting in full force.

It helped that Shridhar was more at home behind the scenes — more interested in rigging the equipment, setting up screenings, and soliciting others to contribute than in putting himself forward as an artist or figurehead. He played a similar role for Charlotte Moorman’s New York Avant Garde Festival from 1971 until at least 1977, including the 1972 festival, held on a Hudson River excursion boat, its wheelhouse transformed by Shirley Clarke into a futuristic I Ching fortune booth. Liz Phillips served spaghetti on an amplified tabletop while Yoko and John circulated among the artists, asking questions. (Liz claims she answered a few of John’s, thought they were very intelligent questions, and then asked him who he was.) Elsewhere visitors took turns on Nam June Paik’s TV Bed, a sculpture comprising a mattress made from six television sets facing up and covered with glass, with two more sets making up the headboard. A camera above the bed captured and transmitted the face of anyone who lay down on it to all the TVs. It’s safe to say that the intricate tech work required to pull all this off was Shridhar’s.

These were tumultuous, formative years. His parents had left for India, leaving him an apartment on West 103rd Street that he shared with an old high-school friend named Conrad Sheff. He transferred from the New School to Columbia and then flunked out, losing his student visa in the process. He managed to get a clerical job at the UN with his parents’ connections, but when that went south he became, technically, an illegal immigrant; to get a new visa he would have to go to India and begin the immigration process from there. Shridhar never made the trip. Then one late night in October 1971 he was mugged on his way back uptown and severely beaten. Sometime afterward Shridhar lost or left his place on 103rd and moved to an apartment in the Village, from which he was evicted — he told friends for health code violations — and eventually wound up sharing yet another apartment with Conrad Sheff, this time on the Bowery.

In December of 1971, Shridhar’s Aleph Null was shown as part of the second night of video programming ever done at the Whitney, a Special Videotape Show curated by David Bienstock as part of his influential New American Filmmaker Series. Roger Greenspun, in a review in the New York Times, described it as “visually stunning,” but complained that it didn’t “escape the tendency toward trivia that characteristically haunts attempts to confer actual movement upon forms that, if still, would suggest nothing so much as the potential for movement… for all their vigorous ingenuity, the tapes seem to channel rather than to free ways of seeing.”

Greenspun’s comment sticks in my mind when I think about Shridhar at The Kitchen: the tape’s failure to live up to its own aspirations seems like a reflection of other sets of contradictions that were taking shape around Shridhar, and a harbinger for more failures to come. Among Shridhar’s close friends from that period there is a lingering sense that, for all of his indispensability, Shridhar was being exploited. Dimitri Devyatkin thinks that “he was beloved, but he was also used. People took advantage of him.” He was the kind of guy who would work all night and didn’t care about money — a good guy to have around. “In the two years I worked at The Kitchen,” Dimitri told me, “I saw a real change. We were getting overpowered by artists and people who could get grants. There turned out to be a lot of egos in that anti-ego culture.” Bob Lewis, a friend of Shridhar’s from Ecolint in Geneva who had reconnected with him in New York pushes back against any nostalgia: “I left the scene because I was fed up with the culture. I found it massively distasteful, self-regarding, self-involved… at some point the focus on fine art became its death-knell.” Another of Shridhar’s old friends, Victor Han, agrees: “there was a lot of infighting, people started splintering.” But Shridhar “was like this magical cog. Well respected, well liked.”

He may have been well liked, but he wasn’t well remembered. In 1973 The Kitchen moved to Wooster Street in SoHo, with an accompanying upgrade in style. After the Vasulkas left for teaching gigs in Buffalo in 1974, Carlotta Schoolman took over video programming. The locks were changed, Shridhar was gone, and for many of The Kitchen’s earliest habitués, so was its charm — its informality and open-endedness, its anti-curatorial ethos and focus on process over product. Shridhar went to work with Shirley Clarke and the TeePee Video Space Troupe, and his seminal role in establishing The Kitchen was forgotten. Or was it erased? DeeDee Halleck was convinced that Woody and Steina Vasulka had wronged him. When I spoke with her by phone, she was still angry, saying that she had confronted the Vasulkas about Shridhar some years ago, at a presentation about The Kitchen’s early days, accusing them of disappearing Shridhar from the institution’s history. At the time, she says, she sensed “a racism that was palpable.”

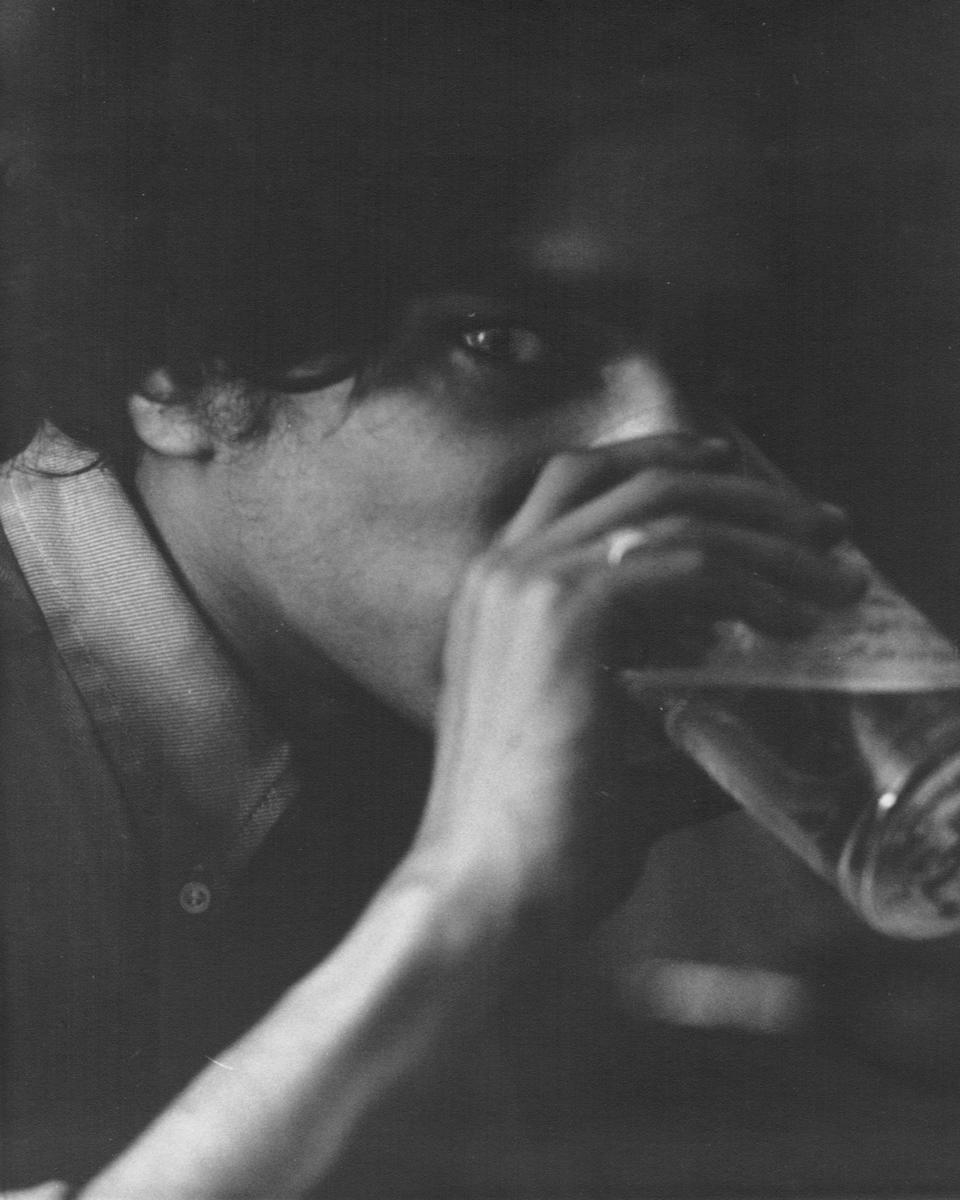

It wasn’t palpable any longer, at least in my own conversation with Steina Vasulka. She remembered him with great fondness, tinged with a sense of failure. “We started to find bottles here and there. That’s how we figured out slowly that he was drinking. Now I know exactly what it means, then I didn’t…”

One of the few completely uncontroversial things you can say about Shridhar: the man loved to drink. By the mid-1970s, it was becoming a big problem.

Was it the booze that made him lose his footing? Did the Portapak invent video art?

These are not dissimilar questions.

3. Infinite Pity

People remember Shridhar with regret because that’s how they remember themselves — their disillusionments and disappointments, their selling out or failing to sell, their settling down and surviving. That whole electro-cybernetic loop and its magic? The salvific promise of feedback? Long since gone. In an instantly famous essay for the inaugural issue of October, published in the spring of 1976, Rosalind Krauss argued that video would save no one. “Reflexiveness in modern art,” she wrote, “is a doubling back in order to locate the object,” whereas the “mirror-reflection of absolute feedback is a process of bracketing out the object.” Video depicted “a psychological situation, the very terms of which are to withdraw attention from an external object — an Other — and invest it in the Self.” The real “medium of video is narcissism.” In the well-looped prison of self-surveillance, the ghost in the machine is Narcissus, with his infinite self-regard; the snake eating its own tail is Onan.

Dear Alex,

Before you build up too much expectation, be prepared for a sad story, with little to show. The devils that tormented Shridhar included his upper-class diplomat parents, their plans for Shridhar, his revolt against his family, his battle with alcohol, loneliness, homelessness, the art world, the gallery and foundation world. There is not much to glorify. I would question what it is you really expect to find and what your motivation is in writing this article. I expect readers to wonder why you decide to write about him. I send you my warmest wishes and hopes for success.

All the best,

Dimitri

At Northwestern University’s McCormick Library I met Scott Krafft, curator of special collections, to look for evidence of Shridhar’s life and movements in the library’s Charlotte Moorman Archive. Moorman, the performer and model for Nam June Paik’s 1969 TV Bra for Living Sculpture, was a cellist, performance artist, and impresario; Shridhar was deeply involved with her New York Avant Garde Festival in the 1970s. There were all sorts of scraps, notes, and postcards with his name on them in the archive. One caught my eye immediately: an unopened letter from the alcoholism clinic at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Greenwich Village, postmarked December 1975, addressed to Shridhar care of Moorman. From the documents at Northwestern it is clear that he was doing a lot of couch surfing, crashing intermittently at Moorman’s apartment up on West 46th Street, sometimes staying with friends.

Krafft suggested we open the letter and see what’s inside, though it’s easy enough to guess — it’s a letter from St. Vincent’s asking him why he’s been missing appointments. There are many notes to Charlotte: promises to clean up, to stop hurting people, to “be better.” His handwriting varies dramatically. There is a hastily scrawled message on the back of a flyer advertising a midnight screening of Ben Hayeem’s The Black Banana: “Finally got my money and am getting a room on a weekly basis. Will give you the no. when I find it out. Thank god this week is almost over! Sorry about all those weird messages.” Another letter, written in an extremely precise hand and arrayed in bullet points, mentions that he is going to Alcoholics Anonymous and apologizes for his role in a “psychodrama” at Charlotte’s house. “I am trying to change,” he says, thanking her for having “helped me in some pretty dicey times… Excuse all the cliches, but sometimes they are true, and I am grateful for everything from the bottom of my heart. I hope I can continue to help with the Festival in any way you find appropriate in the coming year.”

One letter from September 1977 lays out his whereabouts for the next week and how to reach him, including an answering machine and a “live human who pretends that it is my ‘office’ during business hours only.”

Shridhar was a legendary drinker and prone to binges. He got high too, although in the early days that wasn’t really his thing. Leanne Mella, a public-access television activist and frequent visitor to the Whitney’s film and video department in the seventies, remembered a drunken Shridhar falling off a radiator at a party there. Almost everyone I talked to had a story about him getting wasted or getting them wasted or both. “One night Shridhar took me on a tour of where to drink on the Bowery, and how to drink,” Liz Phillips recalled. “I think it was 1973. I would never drink that much again in my life.” Shridhar’s high-school friend Victor Han remembers that he “was the first guy to take me to CBGB. He knew the Village better than anyone I ever knew. He knew the bars, the cheap restaurants.”

1975 was an especially bad year. A world away, Indira Gandhi declared the Emergency and India fell into darkness; Shridhar’s family became unreachable. He had already fallen into a state of emergency of his own, with his closest friends leaving New York or already long gone, taking jobs at television networks or universities. That year Shirley Clarke took a teaching job at UCLA, and disbanded the TeePee Video Space Troupe before she left. The rag-tag, free-spirited atmosphere of the early video scene was professionalizing and institutionalizing.

At a certain point, Liz Phillips told me, “Shridhar started to live in places where he wasn’t easy to find.”

One such place was Anthology Film Archives on Wooster Street, which had finally established a video department and hired Shigeko Kubota to run it. (Anthology founder Jonas Mekas was famously dismissive of video.) Shridhar worked there part-time and sometimes slept in the basement. His mastery of early video machines was becoming obsolete as the technology changed, and his always fragile career was increasingly hitched to Kubota’s star, and that of her husband Nam June Paik. Shridhar made common cause with Bob Harris, a buddy who remained close to him — as close as anyone could be — for the rest of his life, and with another once-ubiquitous video scenester and East Village rambler, the irascible dreadlocked poet, drunk, and video-shaman Al Robbins.

In a posthumous tribute, Paul Ryan celebrated Al Robbins as “a warrior artist… a samurai.” He was a violently bad-tempered man with a penchant for droney, druggy landscapes, complexly interlocking prismatic multi-monitor installations, and glitchy in-camera edits that lent his now-forgotten videos a Brechtian edge. “For Al the beauty of the video signal was its lack of stability,” Bob Harris told me, which goes some way toward explaining what he looked for in people, as well.

Al and Shridhar loved to talk video, and there was more than ever to talk about. The counter-culture that had grooved on the first Portapak transmissions had “enrolled in graduate school,” as historian Jon Burris puts it, and “video history” was being written as a triumphant march of major artists, with a lot of bit players dragging along behind. The canonization had begun with 1976’s Video Art: An Anthology, accelerated with the Bronx Museum’s 1981 Video Classics show (featuring works by Vito Acconci, Dan Graham, Shigeko Kubota, and Nam June Paik), and culminated in the Whitney’s retrospective of Nam June Paik, “the first video artist,” in 1982, which Shridhar was still around to help with. Robert Haller called Shridhar and Al Robbins “dinosaurs.” At the very least, no one could accuse them of selling out.

The two of them were often seen together, hanging out, making video, arguing, drinking, and fighting — not necessarily in that order. “They were both kind of bipolar,” Bob Harris remembers. “Shridhar would be yelling at Al” — the janky edits Robbins favored used to drive Shridhar crazy — “and it would be like a cartoon, except it was tragicomic.” Shridhar and Al sometimes rolled on the floor in half-serious drunken wrestling matches, and it seems like they remained interlocked in that way up to the point that Shridhar’s trail becomes nearly impossible to track.

Conrad Sheff moved to Massachusetts for med school in 1978. “I rarely saw him after I moved to Boston,” he wrote in an email. “He owed everyone, talked crazy so everything he said had only the value of background noise, and he was in and out of Bellevue Hospital for cirrhosis and non-compliant treatment of resistant tuberculosis.” Shridhar had become “a pathological liar.” By the early eighties he was homeless, hopelessly addicted, pissing off his friends, living in the streets. He was spotted here and there, a wino on the East Side, just north of the UN. He leaves the barest of traces: a handbill advertising a screening of Aleph Null at the Mudd Club in the early eighties; another thanking him for assisting on a series of Al Robbins video installations at Anthology and the Brooklyn Museum.

Then he went underground.

4. Null

The giving up of activities that are based on material desire is what great learned men call the renounced order of life [sannyasa]. And giving up the results of all activities is what the wise call renunciation [tyaga].

— Bhagavad Gita, 18.2

“Burma Road” is the name given — no one knows by whom — to a wide tunnel beneath Grand Central Terminal, where a labyrinth of steam pipes created an artificially warm, humid atmosphere. Before Grand Central’s renovations began in 1994, it was one of New York City’s best-known refuges for homeless people.

What they called Burma Road was a disused track beneath Grand Central’s lower level, formerly used for baggage. A 1980 article in the New York Times profiled one man who had had been living there on-and-off for thirty years, whenever things got tight. Times were tight then, what with rising rents and unemployment, and more and more people were sleeping on subways or in homeless shelters, or taking their chances living rough in jerry-rigged tunnel spaces. “To tell you the truth, you know, you get on a drunk and things happen,” one underground man told the reporter.

We don’t know exactly when Shridhar went below. We don’t know how long he lived down there, or when precisely he got sick. We know that the steam pipes that made Burma Road and non-places like it attractive to homeless people during New York winters were insulated with asbestos, and that fans installed to mitigate the heat for maintenance workers ensured that the air in the tunnels was shot through with asbestos particles. (Pipefitters who worked in the tunnels were known as “the Snowmen of Grand Central” because of the white powdery dust that adhered to their clothing.) Burma Road may have been a refuge, but it was no place to live.

Leanne Mella had known Shridhar from film and video screenings in the 1970s. They fell out of touch when she left the city, but she saw him once more, in the mid-1980s, when she was back and working at the Whitney. Shigeko Kubota told her that Shridhar was in the hospital. She found him in the psych ward at Roosevelt Hospital on 9th Avenue. He looked awful, but there was something about him that made her believe him, despite his reputation for tall tales and outright lies. “He had an astonishing clarity about him,” she told me, “an immense self-awareness.” He said that he had been drinking heavily and that he had become involved with a woman who made it seem not only plausible but even preferable to live on the streets. So he became homeless, and then he moved in with this woman who lived beneath Grand Central. And there he stayed, for years. Then one day he got sick or hurt or both and had to resurface. That Leanne was there at his bedside at all was a kind of miracle — when he arrived at the hospital he’d told them, “Nam June Paik. Nam June will pay,” and by pure chance the social worker assigned to him was Peggy Gorewitz, whose husband Shalom was a video artist from The Kitchen’s heyday. She called Paik, and he and Shigeko called people like Leanne. It was not easy to see him, or for him to be seen. Shalom Gorewitz went to see Shridhar at Roosevelt, too, and remembered that “he seemed ashamed.”

Shridhar’s homelessness was a product of his drinking. It was result of the booze in the same way that video art was the result of the Portapak. Both are easy to explain yet difficult to understand, and both have a kind of prehistory, as well: scrying aids like crystal balls, magic lanterns, Merlin’s universal mirror, Maya Deren; nirgranthis and anagarikas, sannyasins and aghorins, a host of Indian holy wanderers, dreadful un-dreadfuls living outside society, and beneath it.

At the risk of romanticizing something with very little room for it, it seems to me that Shridhar’s homelessness and his contrarianism, his assiduous avoidance of gainful employment and his unshakeable anomie, amount to a kind of sadsack postmodern sannyasa. In the dharmasastra texts it is a duty of the twice-born — of Brahmins like Shridhar, who mentioned his caste background often — to end their lives with an act of renunciation and a period of wandering. Sannyasins abandon their hearth-fires, perform their own death-ceremonies, and renounce the world. Shridhar was proud to be a Brahmin, and the storybook ending of a Brahmin’s life is homelessness.

The genealogy of Shridhar’s destitution has the sannyasin on one side and Duchamp on the other. In a famous lecture called “Where Do We Go From Here,” delivered to a symposium at the Philadelphia Museum College of Art in March 1961, Duchamp predicted that the “artist of the future,” in order to mount a real rebellion against the status quo, would be forced “underground,” rejecting the economic, the mediocre, and the bourgeois “exoteric” in pursuit of more difficult esoteric truths. Shridhar was, at his best, most charitably, a failed Duchampian underground man, a video sannyasin without fixed address, income, or family ties. He was all process and no product, abiding in an oneiric videospace, in the “vast ventriloquism / Of sleep’s faded papier-mâché,” somewhere in the video-aleph’s radical simultaneity of worlds. Borges’s short story ends with the author’s opinion that for all of its spectacular power, Daneri’s Aleph was false. So was Shridhar’s. It wasn’t the Aleph any more than Shirley Clarke’s wired-up Chelsea Hotel — its rooms labeled “Paris,” “Tokyo,” “New York” — was the global village. And Shridhar’s trip into the subway catacombs, while on some level voluntary, was the falsest Aleph of all: the deadly dream of a drunkard cut off from history, trapped in a lonesome and recursive hall of black mirrors, a landscape of dripping drainpipes, drugs, diseases, and beatings: the Aleph Null. Rosalind Krauss had decried video’s “prison of the collapsed present.”

“Everyone tried to save him.” “Everyone failed him.” “There was nothing anyone could do.” Tragic choruses never sing new songs. Following Shridhar through the 1980s, through the tunnels, is impossible: a succession of sightings, awkward chance meetings, glimpses of him picking up cans on the Lower East Side, “skulking about” near the UN building where his father once worked, riding the subways on cold days in winter, sometimes coming up to crash-land on a sofa, to try and clean up, to sort out his immigration status, to get a job — at one point he entered a training program to become a copier repairman — and then disappearing again. By 1990, he was dead.

Nam June Paik arranged a memorial service for him at Anthology Film Archives, in the room named for Maya Deren — another Ecolint alum, and an artist Shridhar was obsessed with. Victor Han remembers there being about forty people there. Nam June asked everyone to come up and say a few words, and afterward, his ashes were scattered in a park in Westchester where he liked to play as a child.

“Single channel is the easy way to write video history,” Andrew Gurian told me, pointedly. He was referring to Electronic Arts Intermix’s early decision to archive only single-channel video pieces, eschewing the complex installations and multi-channel works that were considered, at the beginning, the state of the art. But he may as well have been talking about the ease with which Shridhar was elided from that history.

“He was a beautiful person,” Shigeko Kubota told me by phone from Florida, where she spends most of her time now. “But he could not control his mind. I think of him a lot. I miss him.”