Sometime in 1939, on the eve of the opening of the new building of the Museum of Modern Art on New York’s 53rd Street, an intrepid museum employee played a practical joke on her bosses. Her name was Frances Collins, and as the museum’s Director of Publications, she and a friend had concocted an invitation, to be sent to seven thousand distinguished persons, to the opening of what was described as the “Museum of Standard Oil.” The invitation card, printed in extravagant script, came from the “the Empress of Blandings” (a character in the form of an overly fat pig drawn from the English satirist PG Wodehouse’s novels) and would, so it announced, admit “two persons or one person and two dogs.” Inside the invitation packet was a small card that read “Oil That Glitters Is Not Gold” alongside a letterpress engraving of a crown. The overt allusion to then-MoMA president Nelson Rockefeller’s deep entanglements in the world of oil — his father, American industrialist John D Rockefeller, founded the modern oil industry as we know it — did not roundly amuse everyone. Collins promptly lost her job. MoMA, of course, went ahead and opened as planned.

Collins’s remarkable invitation card is part of the raw material of a sprawling, ongoing project by artist Alessandro Yazbek and art historian Media Farzin. Part research endeavor (the two spend a great deal of time with their heads in archives), part historiography, part exhibition-as-conceit, their project takes modernism’s vexed and storied entanglement with the political as its point of departure and inspiration.

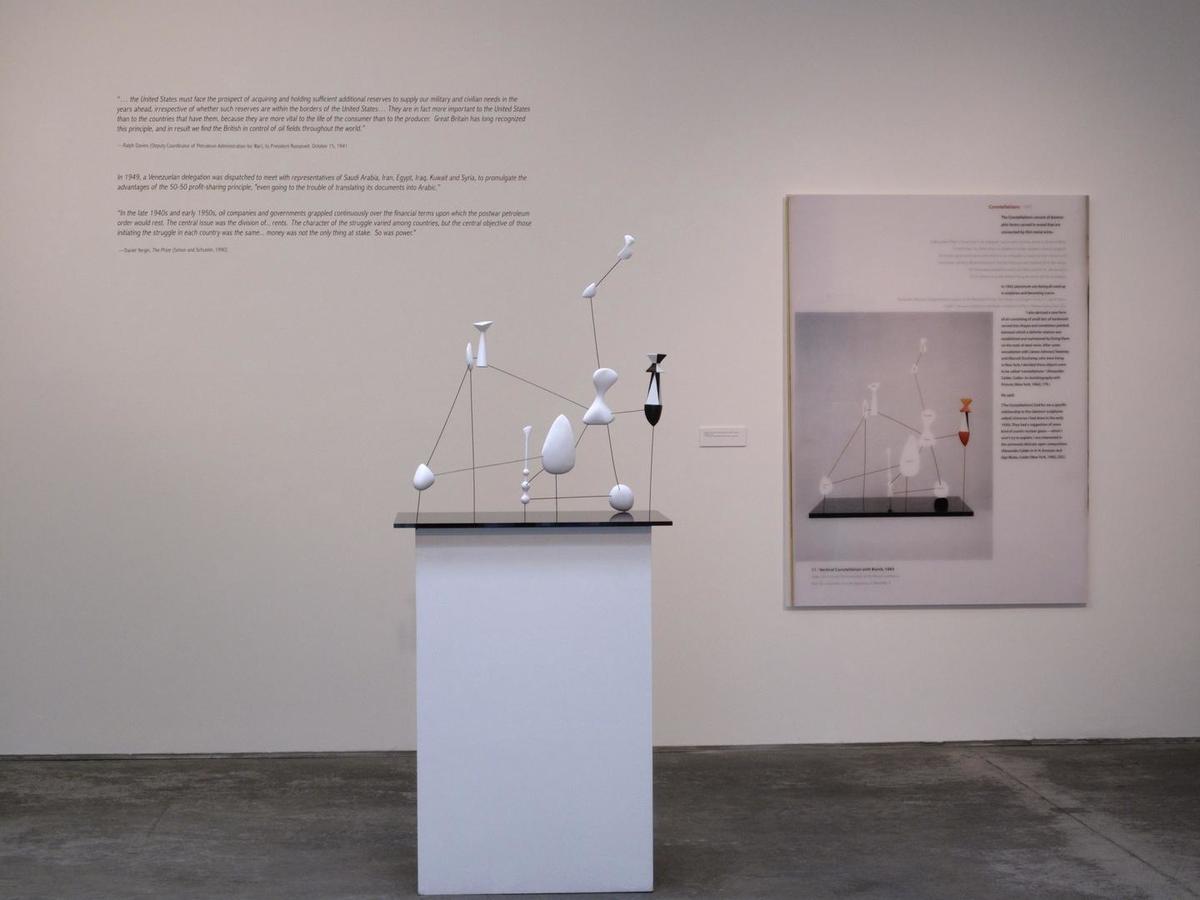

In a recent iteration of their project at Christopher Grimes Gallery in Los Angeles, under the enigmatic rubric “Cultural Diplomacy: An Art We Neglect” (the title was the headline of a 1954 article in The New York Times Magazine), an ambulatory museographic display spread across two rooms included everything from wall charts, documentary photographs, and sculpture to facts, figures, and quotations. The experience of standing in the gallery space evoked the feeling of walking into an exhibition of modern art (Calder-like mobiles abounded), the lobby of the United Nations, and a natural history museum, all at once. Still, the question of whether Yazbek and Farzin’s gesture is artistic, curatorial, or polemical in nature seems an unnecessary one. Open-ended and polyphonic as it is, it was all of that and none of that, and therein may lay its greatest strength.

From the exhibition, we learn that the same Rockefeller who served as president of MoMA was once tapped to lead a special “government-private commission on Latin America” by then-President Franklin D Roosevelt. A decade or so before the CIA founded the Congress for Cultural Freedom, Rockefeller was asked to focus “on the cultural and propaganda side of wartime diplomacy.” Wartime diplomacy at the time largely translated to oil interests, as America realized it had to look outward to satisfy its appetite for petroleum. In 1939, this scion of one of the richest families in America opened a hotel in oil-rich Venezuela — which, incidentally, is where Yazbek, who is of Lebanese and Italian origin, grew up. The Hotel Avila, a classic open modernist structure designed by Wallace K. Harrison and distinguished by its generous verandas, sat in a lush mountainside location just outside central Caracas. One year later, Rockefeller commissioned the American sculptor Alexander Calder to prepare mobiles for the ballroom of the giddily grand hotel.

The work, Didactic Panel and Model of Alexander Calder’s Vertical Constellation with Bomb, 1943, recreates a delicate Calder sculpture composed of irregular and abstract shapes linked by steel wire. A large accompanying wall text, cheekily deemed “didactic,” playfully relabels the elements of the original sculpture— connecting the Shah of Iran to Churchill to Truman to Roosevelt, and so on, as manifest in the sale of Iranian oil to America, the development of hydrocarbons in Venezuela, and even the Manhattan Project. Lo and behold, history is full of accidents. Calder, we also glean from the panel, once said about his open constellations that they “had a suggestion of some kind of cosmic nuclear gases.”

Here, the lines drawn between art and politics are abundant and seamless, and it was this articulation from within the medium of the modern itself that may have saved Yazbek and Farzin’s work from being, well, too didactic. Their installation inhabits multiple modes, documentary and aesthetic, and from there, works its way out. And while at times it may seem like the works could benefit from less telling — the quotes sprinkled here and there do feel excessive at times, with their ah-ha! conspiratorial juxtapositions — the visual experience of the sculpted form makes up for any gratuitous pedantry.

Yazbek and Farzin’s next project will involve navigating the world of cultural diplomacy as played out in Iran under the late Shah. Iran, which is where Farzin is from, has also been awash with oil and, like Venezuela, has a long record of projecting itself on the world stage through ambitious infrastructural — and even cultural — projects. After all, the Shah and his pretty wife Farah launched an avant-garde arts festival in the southern city of Shiraz in the 1960s and built up an impressive modern art collection, too. That congruity between the two geographies — Iran and Venezuela — emerged in explicit fashion in one of the photographs on display in the Los Angeles show.

Anyone who has visited the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art may have noticed a Calder mobile (circa 1946) on permanent exhibition, dangling above the modern building’s spiral staircase (in the aftermath of the Islamic Revolution, the grim-faced portraits of Ayatollah Khomeini and the Supreme Leader were installed just behind it). Adding the merest patina of irony, at the base of the museum’s winding staircase is a work by Japanese artist Noriyuki Haraguchi, in the form of an oversize, square-shaped steel container. Within the container’s shimmering depths, visible as museum-goers lean over and gaze downward, sits a pool of oil, perfectly reflective.