Bethlehem

As if by Magic

Bethlehem Peace Center

September 6–October 6, 2006

As if by Magic couldn’t have been a more apt title for a recent exhibition in Bethlehem. After all, it was a bit like magic that exhibition curators Charles Asprey and Kay Pallister were able to summon up an A-list of 26 international contemporary artists, including Martin Creed, Daniel Buren, Lawrence Weiner, Douglas Gordon, and Damien Hirst. It was a bit like magic that they exhibited their work in Palestine, at Bethlehem’s posh Peace Center — a museum-like space that nevertheless has never previously shown contemporary art of this scale and caliber. This kind of show ordinarily takes place in Tate Modern, not in Bethlehem.

Asprey and Pallister commissioned European and North American artists to produce new work or adapt existing work in order to allow it to be produced in Palestine. As most artists were unlikely to be able to travel there to install their work personally, they each had to produce an affordable “recipe” for their work. Nothing ingenious, really — “recipe art” has been done and done since the days of Do It, the book/exhibition project initiated by e-flux/Revolver and edited by Hans-Ulrich Obrist. However, Do It had never been done in or for Palestine, and there had never been an exhibition specifically aimed at combating the local population’s jail-like circumstances by giving them a glimpse of an art world beyond their shrinking borders.

I was one of a group of about 40 people who took the highly anticipated, not-so-jolly bus ride from Ramallah to Bethlehem, organized by the exhibition’s master planner, Samar Martha, to attend the opening and supplement the virtually non-existent audience for contemporary art in Bethlehem. The handful of Bethlehemites who did attend mainly came out of curiosity and were mostly oblivious to the flashy names on the white labels alongside the works. Ramallah, with its arts centers and cinemas, tends to attract the cultural crowd, so we had to take a field trip to save the day. The bus ride itself almost overshadowed the event: as one traveling viewer said, bypass roads, settlements, and checkpoints “are more real and ‘engaging’ than some stripes on a wall or string hanging in midair.”

Despite this cynicism, As if by Magic had undeniable flair when it came to political witticism and commentary. While the international community once turned a blind eye to the Middle Eastern art scene, Palestinian practitioners are now getting a look-in, from the Oscars to the biennials; but it’s still rare to see work accompanied by or reviewed with any sense of criticality. While Sally O’Reilly and Sacha Craddock, British critics who attended As if by Magic, insisted on describing the work according to its import in art historical terms, from a local perspective, it was fascinating simply to let the context of the place eat it up.

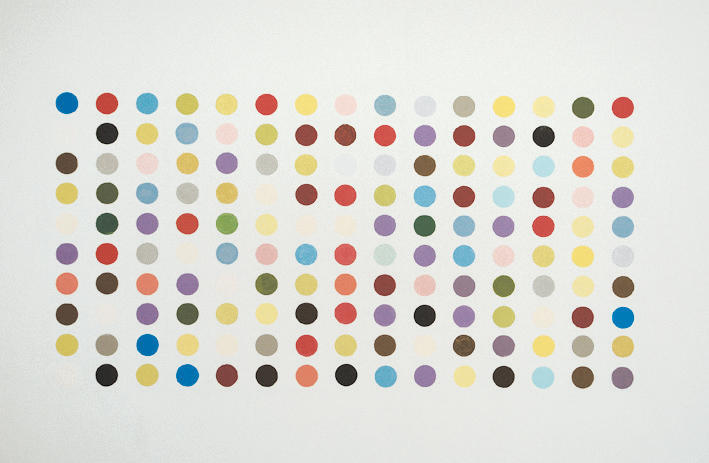

Isa Genzken’s Untitled, a wall motif of two PACE (the internationally familiar Italian peace design) flags, painted side by side but in reverse, with the rainbow colors adjoining but not meeting, was overtly political, if a tad too simplistic. Jakob Kolding’s architectural exploration of urban utopia was critically reminiscent of the modernist Zionist urban planning ideologies that formed the backbone of the state’s early expansionist strategy. In his poster-like interventions, Kolding constructed a series of cut-and-paste photomontages, structured collages with visual and textual elements, which questioned the contours of this “utopian dream.” The references provided a further critical reading of how spatial politics and design can become tools for social control and — in the specific case of Palestine, and the ever-expanding suburbia of orderly Israeli houses and settlements — of political control. Daniel Buren’s Untitled green striped wall; Martin Creed’s Work No: 594, a mathematical construction of fading black columns stretched to the height of the wall and decreasing; and Pawel Althawer’s Wall, a designated space for children to draw on, all alluded to the one and only Wall.

The strongest political statement in the exhibition was Mauricio Guillen’s site-specific installation. (Guillen was the only artist to attend the exhibition, ignoring the curatorial precept of “keep your distance.”) Despite usually working with photography, he instead chose to tie together two strings, one originating from the city’s Catholic church and the second from a lawyer’s office on the other side of the square — a good 200 meters or so apart — and knotted inside the gallery on two blades of an open pair of scissors. Needless to say, this process involved a mass of negotiations and permissions, not unlike our many peace processes.

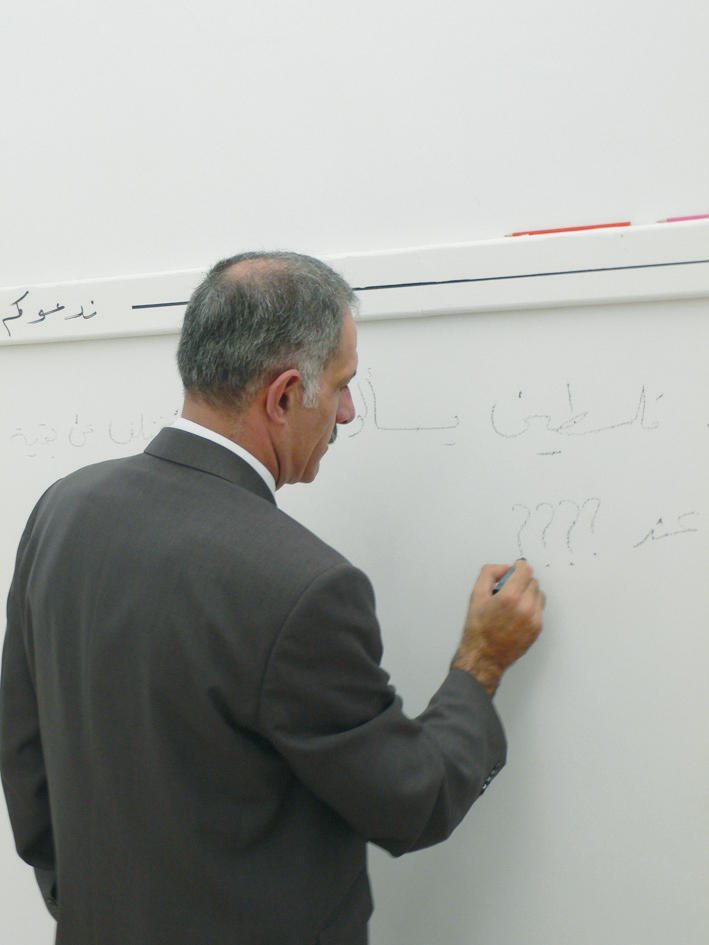

Interestingly, many of the artists used language and text in their works. Douglas Gordon, in his insightful piece A Few Words on the Nature of Relationships, reversed a statement and mounted it on the wall: “Open your mouth, close your eyes/ Close your eyes, open your mouth,” brought to mind the inescapable duality, binary existence and endless yo-yoing that characterizes life in Palestine.

And finally, other works alluded to the language of miracles. Nathan Coley drilled a statement on the wall of the Peace Center — cheeky if seen from a religious perspective and spot-on given the politics of the place. Despite the small magic of the show’s taking place, Coley somehow summed it all up: “THERE WILL BE NO MIRACLES HERE.”