Boston

Kader Attia: Sleeping From Memory

Institute of Contemporary Art

November 14, 2007–March 2, 2008

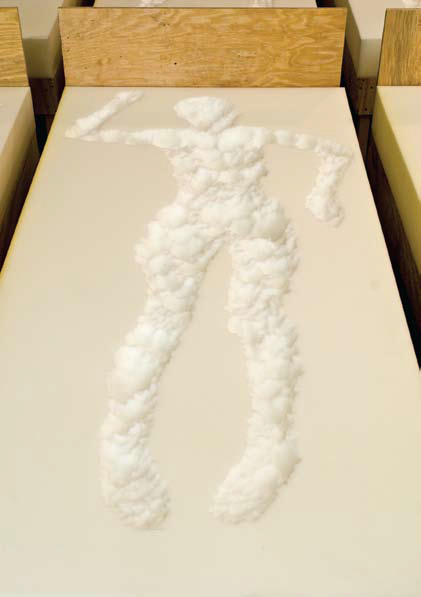

In Sleeping from Memory, recently at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art, Kader Attia excised the forms of sleeping children from a composition of fleshy foam mattresses on shoddily constructed bedframes reminiscent of those he slept on as an Algerian immigrant living in the suburbs of Paris.

Across the river from artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s pile of candy, on concurrent display in Cambridge, Attia’s installation exposed a paradox at the heart of the late Gonzalez-Torres’s formal and ideological interrogation of the process and politics of recollection.

In disrupting the right angles and flat planes of what otherwise would have been a minimalist grid of roughhewn plywood beds, Attia was, like Gonzalez-Torres, intent on inserting a politics of the body and of memory into minimalist forms usually hostile to such concerns. In carving out impressions left by bodies borrowed from Boston-area youth, Attia, unlike Gonzalez-Torres, presented the residual effects of bodies in space as a sort of residue in reverse, in which memory doesn’t so much accumulate in objects and spaces as wear them down and away.

If Gonzalez-Torres’s iconic mounds of gleaming gold-foil-wrapped candies were saccharine substitutions for flesh — his way of capturing the immigrant experience as subaltern — then Attia presented nothing but wrappers, the waste memorializing a physical encounter between bodies and objects rather than an approximation of the body’s weight and heft.

Anyone calling Attia’s exhibition “trash” (it was, in truth, aesthetically rough around the edges) was, then, perhaps more astute than accusatory. Rather than presenting memory as embodied in objects or space, Attia presented it as an act of consumption, in which one ingests and digests spaces and objects in the process of encoding them in one’s mind. In this light, the scooped-out forms of sleeping children were less the fleshed-out memories of bodies once present and more the residual damage from memory’s cannibalistic siege on spaces and objects.

Attia’s works often perform a kind of violence. In his Flying Rats, first shown at the 2005 Lyon Biennale, mounds of birdseed were patted into disturbingly burger-esque approximations of small children, who were accordingly sandwiched and stuffed into sunbonnets and sailor suits and subjected to the merciless pecking and prodding of pigeons in a cage that doubled, in not-so-subtle fashion, as a metaphor for an “urban jungle.” Over the course of the biennale, the pigeons transformed children at play into an apocalyptic nightmare of scattered seed.

In other works, refrigerators etched with windows and clumped together like a city skyline (Fridges, 2006) and figures of praying women formed out of aluminum foil like fancy containers for restaurant leftovers (Ghost, 2007) sculpt the act of consumption into a vision anything but filling and fulfilling. The empty refrigerator bellies and aluminum-foil ladies reverberated with Attia’s (at times heavy-handed) interrogation of Western capitalism and consumer culture.

Attia’s brand of consumption empties out and absents rather than filling in a tried-and-true critique of the dynamics of capitalism. His grappling with the ill effects of globalization and the pervasive international influence of Western modes of consumption on a purportedly purer non-Western realm often obscures his more resonant examination of memory as both space and process.

For Attia, memory is anything but architectonic and anthropomorphic. Through Sleeping from Memory, Attia disabled the near-ubiquitous notion that the psychological structure of memory can somehow be conveyed through architectonic constructions, as in the omnipresent double entendre that wants to consider the space of memory both a metaphoric structure and a real built environment.

The concrete structures occupying the gallery were not meant to materialize memory as process or as space, but rather to expose the implied absence at the heart of negative space, evacuating the efficacy of any attempt to cram that absence chock-full of matter.

Attia completed Sleeping from Memory during a residency at the ICA that coincided with the grand opening of its Diller Scofidio + Renfro–designed building. Situating a work about remembrance in a sparkling new structure with little institutional memory to speak of was one way to disengage the space of memory from any architectonic implications. More covertly, Attia imagined the new museum as a site of possibility that artists needn’t necessarily fill with objects but can instead leave resonantly empty, a space beyond consumerism, colonialism, and their critique.