Dubai

Brute Ornament

Green Art Gallery

March 19–May 5, 2012

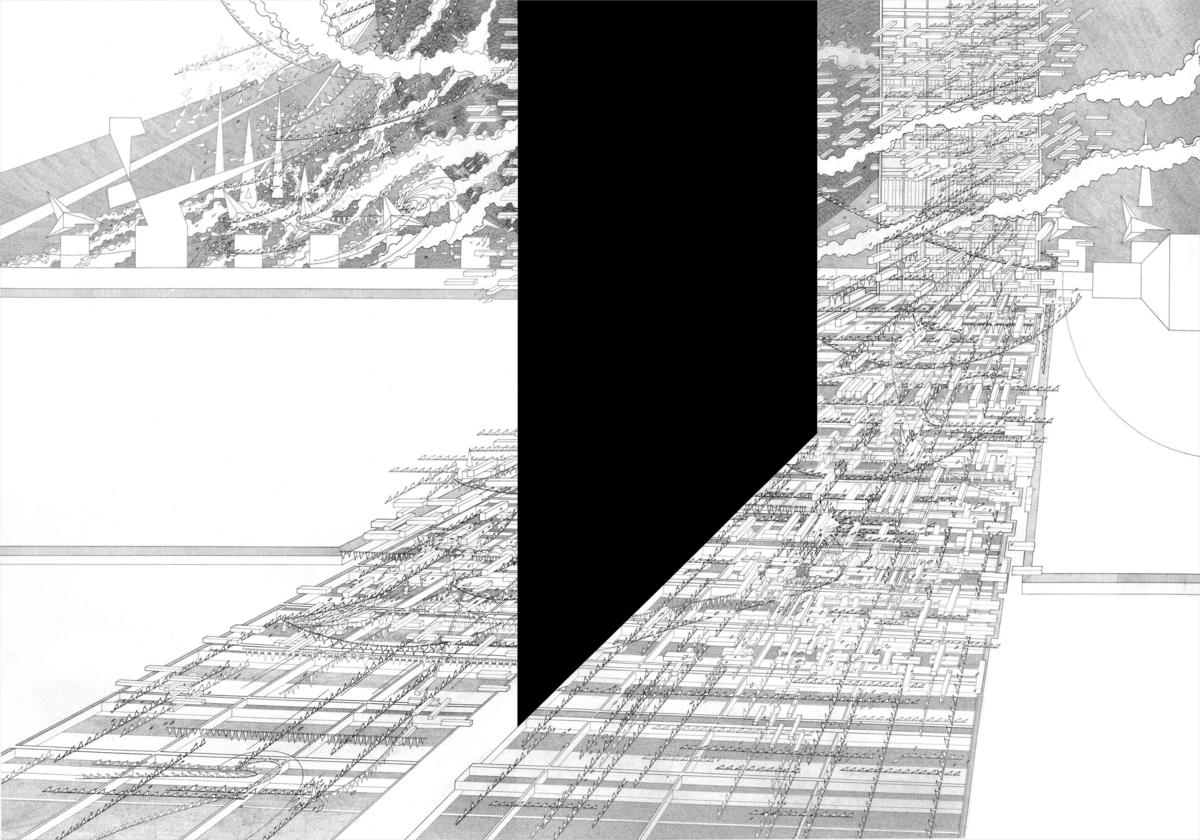

Kamrooz Aram’s paintings are as gorgeous and gooey as Seher Shah’s drawings are prim and precise, and yet there is something unexpectedly sinister about them both. A black geometric form appears ready to fall like the blade of a guillotine in Shah’s graphite and gouache on paper Object Relic (Unite d’Habitation), from 2011, all delicate urban grids and dancing flames below. Paint drips like blood from a wound in Aram’s Palimpsest (for Beirut) and Palimpsest (for Twombly), both 2011, except the source here is a smattering of almost sickly floral blooms. Both artists evoke violence in purely formal terms — through slicing or intruding shapes, the appearance of bruised or punctured or pressurized surfaces, or compositional spaces that seem unsettled or knocked out of balance or on the verge of collapse.

It is to curator Murtaza Vali’s great credit that he paired up Aram and Shah in the exhibition, ‘Brute Ornament,’ for no other obvious reason than to propose an idea — that meaningful tensions arise from the meeting of modernity and tradition when it is cast as a conversation between abstraction and decoration. Vali upends the assumption that modernism simply purged itself of ornament because the decorative was useless and had no function. In the curatorial statement accompanying the show, he argues instead that ornament played an essential part “in the move towards pure abstraction that was modernism’s endgame.”

For Vali, without overdoing it on the biographical or geographical fronts, this allows for a far more complicated, twenty-first century way past postcolonial reading of the art historical relationship between East and West. Both artists have their research and their references down. They knowingly delve into different histories of Western modernity — Abstract Expressionism, Cy Twombly, and Frank Stella for Aram; Brutalist architecture, failed utopias, and Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation housing project in Marseilles for Shah. At the same time, they coax those histories into the same space as decorative traditions that are “culturally specific,” to borrow Vali’s overcautious phrase, Eastern in their allusions to Islamic art and architecture, and, perhaps most importantly, part of a daily practice that is repetitive, labor-intensive, singularly focused, and effectively ritualistic. The old East-West divide thus becomes a mix of back-and-forth movements and migrations, a kind of cross-fader sliding between different approaches to addressing a subject, making a mark, passing the time, and reaching an artistic end.

Indeed, there is a compelling push-me, pull-me quality to the work of Aram and Shah alike. Aram’s oft-repeated pattern of black and white diamonds and triangles appears to fluctuate between foreground and background, forever switching places with flowers, plants, expressive brushstrokes, pools of color, and gestures of erasure, begging the questions, which elements are merely ornamental and which are capable of generating meaning, and could they be one and the same? Shah’s drawings likewise play with the order and breakdown of pale grids, which seem to advance and retreat around bold planes of solid black. Shah counterbalances the heaviness of those forms with the delicacy of her thousands of tiny flagor flame-like shapes, all strung together and swirling alongside curvy lines, suggesting either cloud formations or an explosion’s smoke (described as such, her work sounds like Julie Mehretu’s, but stand in front of Shah’s Emergent Structures triptych or Unit Object series and there’s much more that holds you and sticks in your mind).

With ten drawings by Shah and six paintings by Aram, 'Brute Ornament’ not only pursued a commendable theme and raised a vexatious set of questions that go to the heart of modernity’s anxieties about ornament, but it also caught both artists at crucial moments in the development of their respective practices. Shah’s earlier work was as black and white as her current series but the compositions were all crammed and busy, with a surfeit of crosses and crescents and references to the crusades (ongoing, architectural, psychological, and spectacular). Aram’s work, by contrast, has developed a fullness and lushness that was missing from his previous paintings and collages on paper, such as the series 7000 Years, from 2010, which was punchy and graphic and a touch too didactic. Somehow, between Shah paring down and Aram building up, Vali brought them together at exactly the right time.

What, then, of the place? What does it mean for two artists from New York, and before that from Pakistan and Iran, to have a joint show in Dubai? In a way, of course, it was perfect, emblematic of the city’s many diasporic communities crossing paths. Or maybe it was a sign of Dubai’s status as a tangled knot in the threads of travel, trade, asylum, and economic migration that people follow, not without pain or suffering, from one place to another. The faint but deep-sounding resonance between Shah’s pencil-drawn skyscrapers and Shumon Basar’s contribution to the catalogue, an excerpt from his forthcoming novel about Dubai, suggested a sub-theme concerning the city itself, heaped as it is with all manner of East-West, tradition-modernity, pastfuture, and generic-specific anxieties.

More practically, though, 'Brute Ornament’ announced the arrival of the Green Art Gallery 2.0. Possibly the oldest of the current crop of commercial art spaces in Dubai — established back in 1995 — Green is, in effect, the Emirati outpost of the Atassi family art business. (The original Atassi Gallery opened in Homs in the 1980s, moved to Damascus in the 1990s, and stood apart from the dubious market creep that characterized the Syrian art scene before the uprisings began in 2011. Run by Mona Atassi, it is still open but for the time being barely functional.) Yasmin Atassi, Green’s current director and daughter of the gallery’s late cofounder, Mayla Atassi, is very second-generation in both her business acumen — first she moved the gallery to the postindustrial Al Serkal Avenue complex; then she took it to Art Basel this year — and her aesthetic vision. 'Brute Ornament’ was the first show organized by an outside curator, and it marked the start of a promising new publications program. Dynastic, yes, but it’s not a bad way to draw upon history to create something new.