We should not be ashamed to acknowledge truth from whatever source it comes to us, even if it is brought to us by former generations and foreign peoples. For him who seeks the truth there is nothing of higher value than truth itself. —Al-Kindi (c. 801–66)

Writing is a powerful tool, the very essence of human history. With the invention of writing the human race bridged the gap between the ephemeral world of matter and the eternal world of the spirit. Writing has immortalized the fears, desires, and stories of many civilizations, helping them survive the relentless progression of time. Regardless of the many graphic forms it took, in ancient times writing was considered a potent symbol of supernatural power and divinity. In the East, letters were considered the only worthy carriers of holy scriptures and divine revelation. They were the word of God materialized for human eyes to perceive. A separation between the visual appearance and the meaning of texts was unthinkable, just as the separation of the body from its soul.

In Eastern cultures letters were shrouded with mysticism and supernatural power. The Egyptians saw in their hieroglyphs a sacred gate to the secrets of the world. They believed that through words and images they could create immortality (and to a certain extent they succeeded), and that their word-images had an inherent eternal life and magical power. The Sumerians impressed their script in clay tablets, not simply because it was an abundant and easy-to-use resource in Mesopotamia, but also because the act of writing in clay was a ritual enactment of their myth of creation. They believed that clay was at the origin of life and that man was created from a handful of soil. The Chinese considered every brushstroke of their characters to be the bearer of the soul and spirit of the universe. The mysticism attributed to writing is not confined to ideographic writing systems. In the Islamic tradition, the development of point to line, of light to movement and of the Aleph (the first letter of the Arabic alphabet) to the rest of the alphabet becomes the story of creation itself. In religious texts, the calligraphic perfection that may sometimes obscure the reading of the text forces the reader to go beyond the precise meaning of the words and into the radiating beauty of the holy message. Ornamentation is designed to mimic in intricate fashion the infinity of God’s creation, and to imply to the faithful the mirror-image concept of the reciprocal reflections between the spiritual and material worlds. For many ancient cultural and religious traditions, the world of writing is a metaphor for life; its elements are the creatures and its books the world.

The Arabic letters are at the center of the Islamic story of creation. In the beginning, God created a point of light (like the Hamzah, a diacritical mark signifying the very short consonantal sound and represented by a tiny sign on top of the Aleph). While God looked upon it, the point began to drip, becoming ink, and the letter Aleph was formed. The Aleph, the first letter of the alphabet, is the first moment of creation when non-matter (the Hamzah, the point, the light) becomes matter (the Aleph, the line, the ink) in the flux of movement. This principle of point to line, of non-matter to matter can also be applied to the Arabic numbers where the point represents zero (the incarnation of nothingness, or non-matter), and the line represents number one (the beginning of all numbers, the first and simplest material form). In addition to being the beginning of life, the Aleph becomes the axis of the world. Through its infinite rotational movement around itself, it draws the circle that regulates the shapes and proportions of all the other letters of the alphabet. Through motion, it gives form to the whole alphabet, and joins non-matter (ideas) to matter (writing). The circle is another essential metaphysical concept, a symbolic way of expressing the philosophy of Tawhid—the divine unity of the diverse yet harmonious creation. Therefore with these three elements of point, line and circle, and the geometric structural principles that govern their inter-relationships, all the Islamic applied arts were unified. Encouraged by the prohibition of figurative representation in Islam (intended as a means of banning the worship of idols and pagan gods), Arabic calligraphy and decorative arabesque motifs achieved the status of spiritual art through their fusion of sacred texts and aesthetics.

Mystical manifestations in contemporary art and design

In the visual arts we frequently run into circles where we find ourselves looking back to the past for inspiration and the regeneration of creative energies. Like a Philip Glass score, history does not necessarily repeat itself in quite the same way, but rather repeats itself with variations and remixes of old themes in a new garb. This too applies to contemporary Islamic art and design. The theme of poetic mysticism returns in a new form through the work of artists from different geographical backgrounds. Three main themes surface, each conveying a similar message yet differing in their mode of visual expression. There might be mysticism in geometric and repetitive motifs, mysticism in the symbolic play between light and darkness, and mysticism in the poetic marriage of opposite elements (imagery and abstract calligraphic forms). These themes can best be discussed through the work of three very different artists, all of whom use Arabic letters as the central element in their art: Samir Sayegh (Lebanon), Khaled Al Saai (Syria), and Reza Abedini (Iran).

In Samir Sayegh’s work, the principle of Tawhid is expressed in an art form that goes beyond decorative arabesque motifs to include Kufi letters as its central module. The artist creates harmoniously balanced and poetic compositions that deviate from the very tradition that inspires him. In the Islamic art tradition, calligraphy and decorative arabesques are seldom combined, but in Sayegh’s work the two are merged into a seamless whole. Here the letters take on the role of the very building block on which the whole design of the painting is constructed. These are compositions that expand in endless rhythms and returns, mimicking the very concept of the emanation from and return of the soul to its original creator. Harmony is created between the perfection of the detail and that of the whole, leaving the viewer in a state of meditation vacillating between the two. Moreover, some of Sayegh’s paintings consist of bas-relief woodblocks, carved and then painted, which add to the tactile quality of the abstract image. The artist makes literal allusion to the ‘constructed’ nature of the surface, and in so doing forges a link between the material world and the spiritual experience of gazing into eternity. His work invites the viewer to reflect upon the philosophical implications inherent in the artwork the mirroring of the smallest detail into the greater scheme of the whole. It is a poetic celebration of the unity between the spiritual and material states of existence. Through their perfectly balanced and arranged geometry, his paintings represent a state of perfection that one aspires to achieve through meditation in order to attain a heightened state of awareness.

This poetic spirituality is approached diametrically in the paintings of Khaled Al Saai. Where geometry is the binding element in Sayegh’s work, light is the central theme of Al Saai’s paintings. In his painting The Valley of Colour, letter forms in Diwani Jaly (Turkish) style crowd the landscape with an upward motion toward a brightly lit sky. They are like earthly souls yearning to return to their origin of pure light. In earth tones and shades of green and ocher, they mimic plant forms that grow in joyful movements towards the sunlight reaching for their very source of energy. As Albert Hourani has noted in A History of the Arabic Peoples (London, 1991), “the symbolism of light was common in Sufi as in other mystical thought […] Just as the soul was created by this process of descent from the First Being, a process animated by the overflowing of divine love, so human life should be a process of ascent, a return through the different levels of being towards the First Being, by ways of love and desire.”

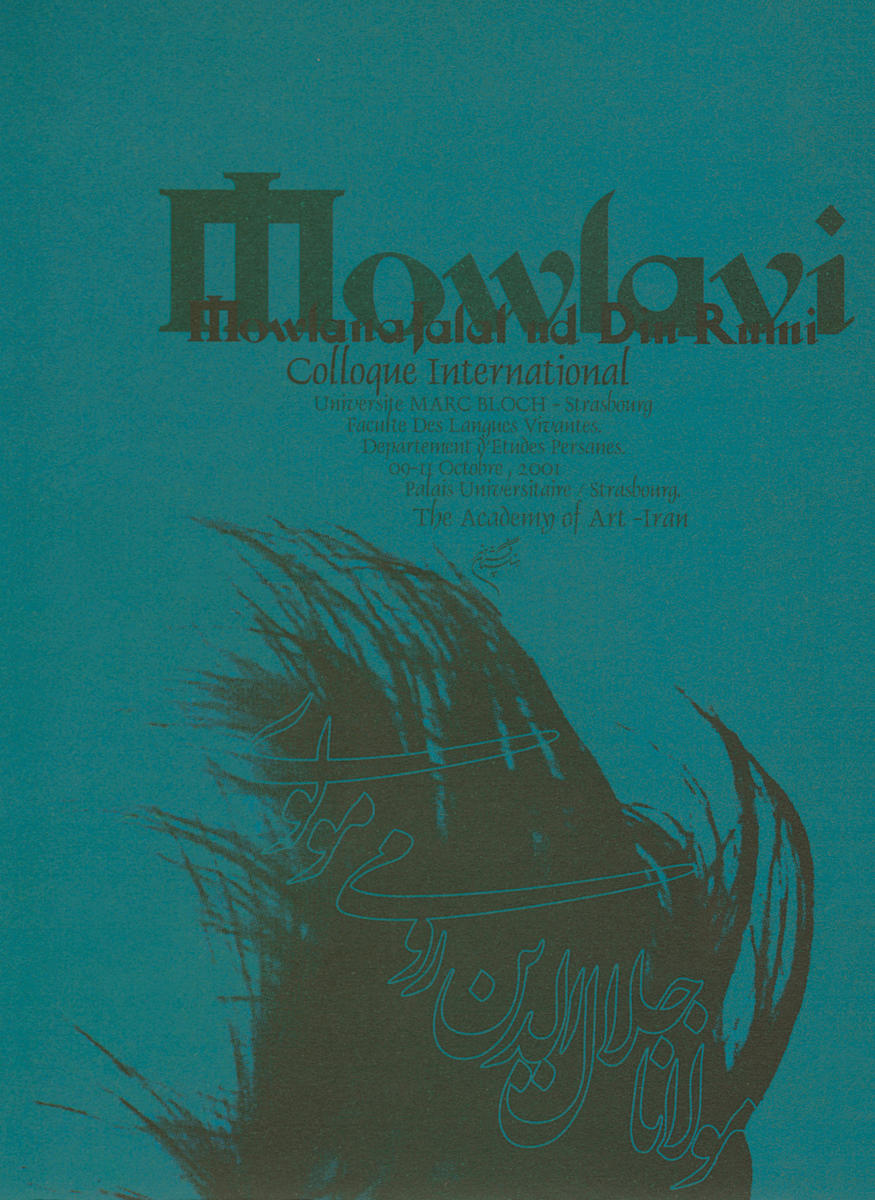

In another painting entitled Sunset, letter forms in multiple and harmoniously matched complementary colors dance in mirror image (as in the heavens, so also on earth) around a light source that holds them riveted to the center of the composition. The painting transfixes the viewer, with an invitation metaphorically to take part in this concentric dance, making allusions to the entrancing dances of twirling dervishes in a state of exaltation and spiritual ecstasy. These allusions to a certain rhythm and spiritual tempo are easily explained by Al Saai’s source of inspiration, namely the music of poetry. It is poetry that has compelled him to search for “the image of meaning,” and for an artistic rhythm that can give to calligraphy a sense of meaning without the words themselves needing to be read. This is his invitation to transcend the barriers and restrictions of languages that can hinder a universal kind of understanding. In the philosophy behind Al Saai’s work we hear the resonance of an older poet and philosopher, Mawlana Jalal al-Din Rumi, who said: “Explanations by words make many things clear, but love, unexplained, is clearer” (quoted in Nabil Safwat, The Harmony of Letters, Singapore, 1997).

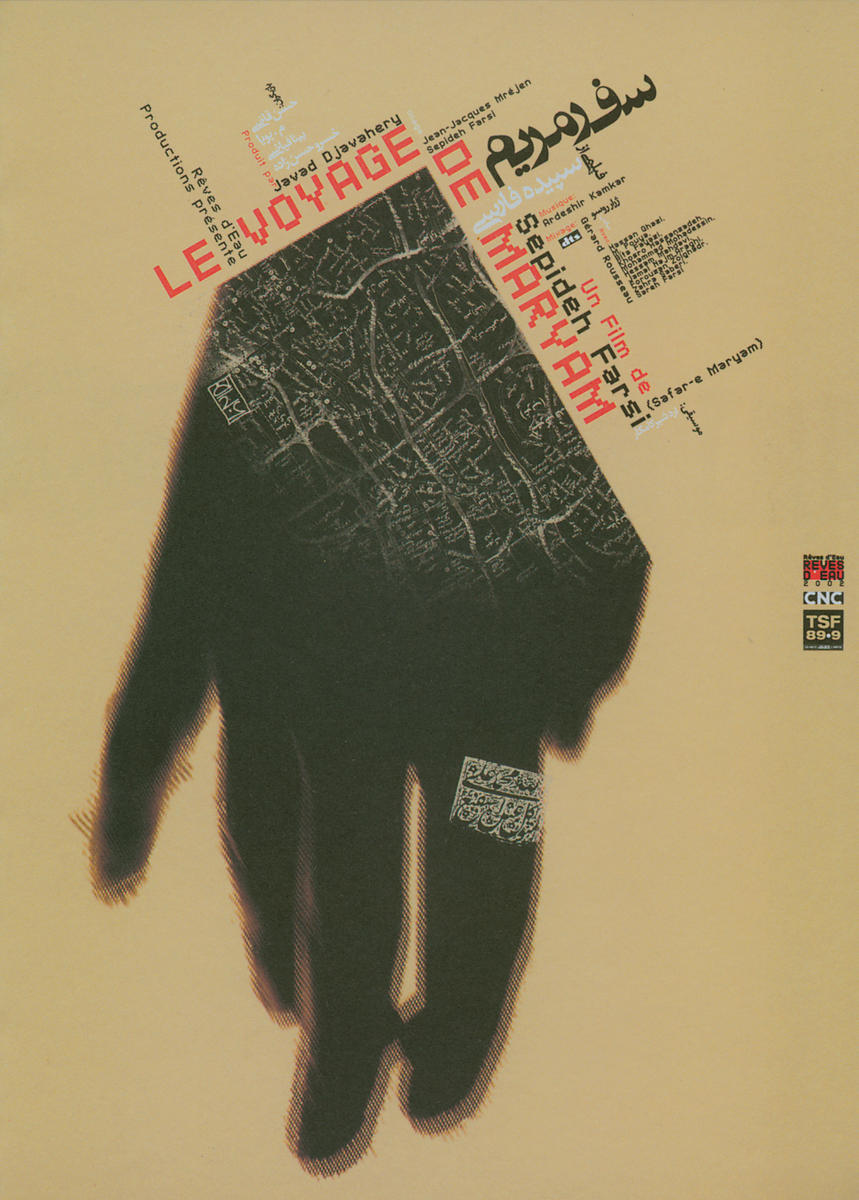

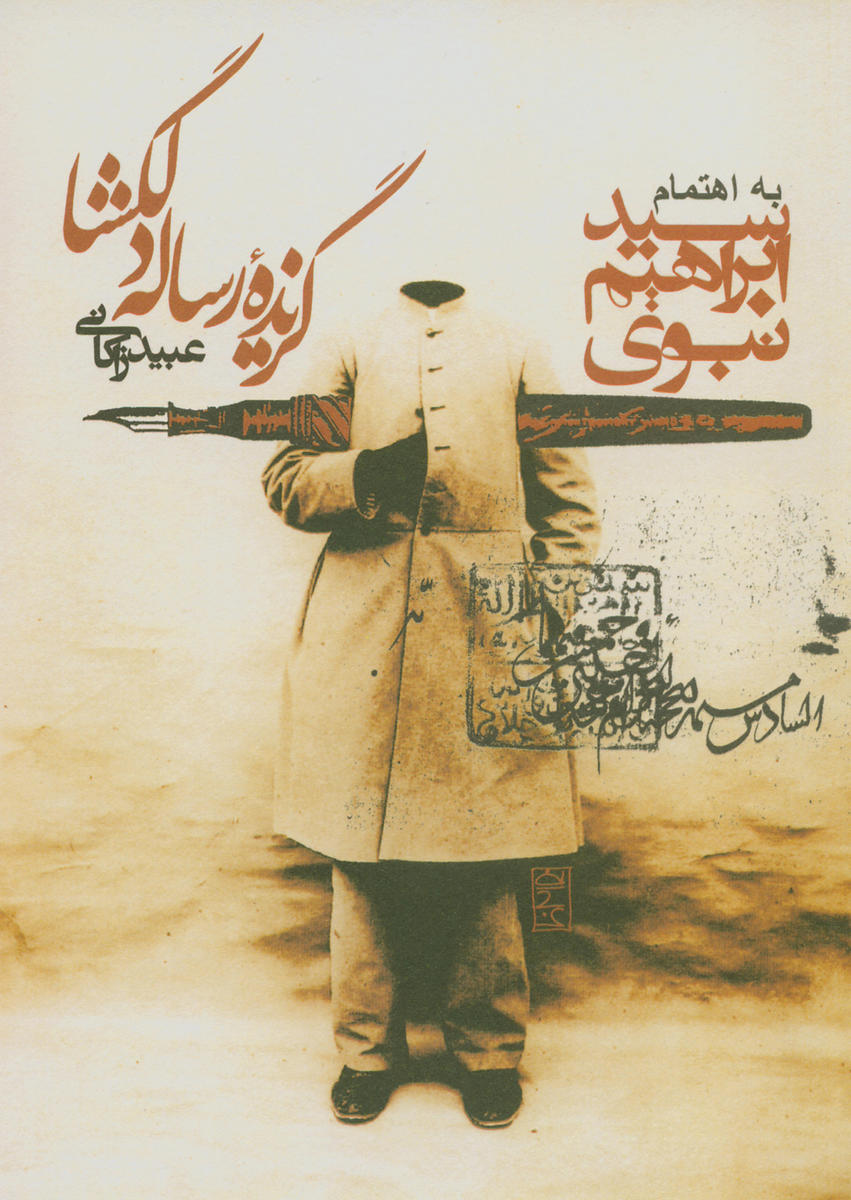

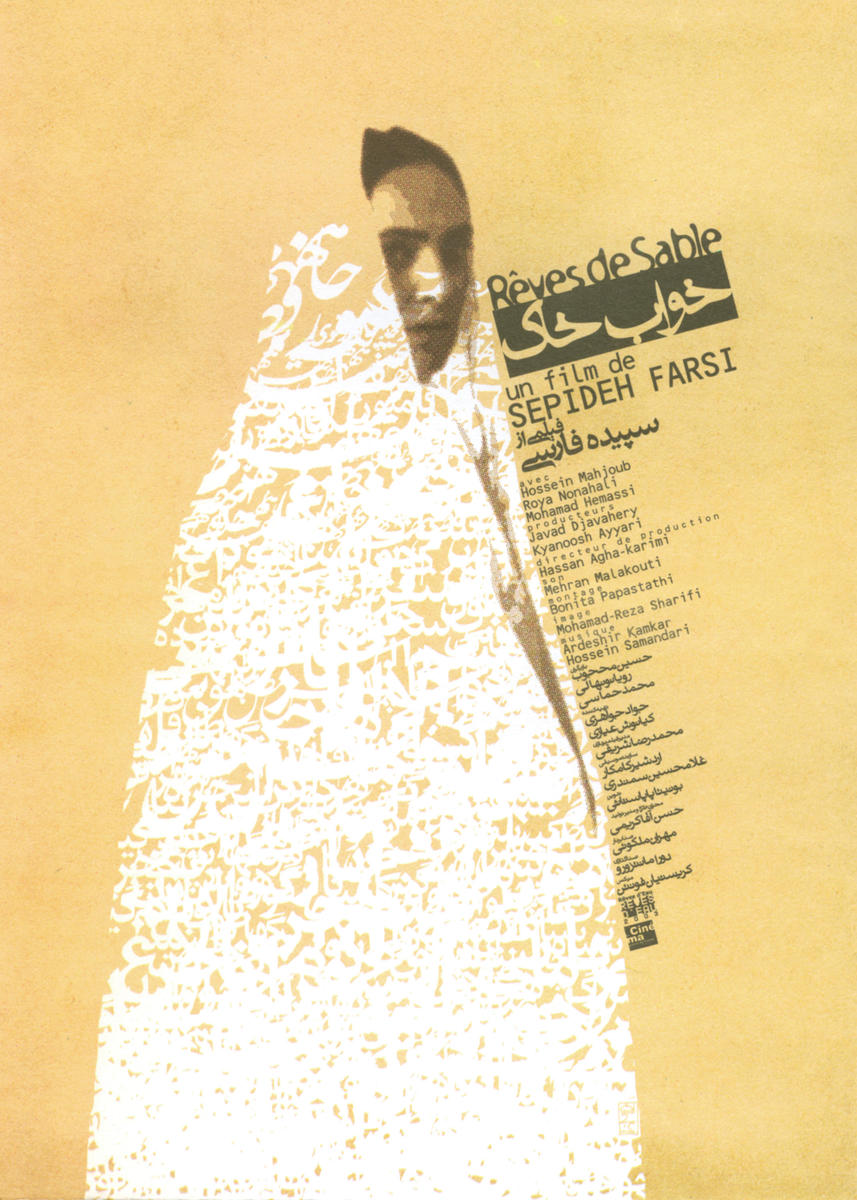

Unlike Sayegh and Al Saai, Reza Abedini creates work that is of a more pragmatic nature. His body of design work is focused on assignments for Iranian and international cultural institutions. In it there is a clear resonance of the poetic compositions of Iranian miniatures and manuscripts, where painted images sat side by side with poetic texts, often written in the free-flowing Nastaliq and Shikasteh styles (hanging diagonally across the page). In Abedini’s work the image and the letter forms are merged in very fluid and sensitively organized compositions where one cannot be separated from the other. With his ability to weave the text into the image using his own lettering, he creates a finely tuned balance between traditional Iranian art and modern typographic compositions. His posters and book covers vibrate with hidden messages in a playfully engaging yet spiritually enlightening way.

Abedini’s work is representative of contemporary trends in postmodern graphic design, where the text is entirely liberated from the constraints of typographic conventions. The text becomes the image, a visual element to be seen and understood intuitively, rather than read and understood intellectually. These are distinctively cluttered compositions, in which the Farsi-style lettering does not necessarily act as a neutral support to the image, but blends with the images to create a tightly woven fabric that occupies the space of the poster like a self-confident monument. His posters create spaces that reflect the lively environments of modern cities, throbbing with mixed textures, smells, and graphic elements from various sources and origins, mixing old and new. The tension created by the eclectic mixes he achieves through his work unifies his native culture with that of the global civilization of contemporary cities, and expresses the transient feel of a new kind of spiritualism.

These mystical manifestations in contemporary Islamic art and design are a hopeful sign of a future that will carry on expanding, changing, mutating, and developing new forms of expression that reflect and comment on the culture of the time. Art (Islamic or otherwise) will carry on recycling some of humanity’s basic and vital needs, refitting old traditional forms into new ones, and going beyond the seen into the realm of the universal quest for spiritual fulfillment.