At the 2005 Sharjah Biennial, artist Peter Stoffel attempted to get himself banned. Taking inspiration from the notices placed by employers in local newspapers, featuring the names, nationalities, passport numbers and mug shots of ex-employees, Stoffel requested that the biennial’s organizing body fire him and announce his occupational demise in the same way. Other potential employers — presumably those organizing another biennial in the UAE — would be hiring him “at their own risk and responsibility.” At the same time, the biennial would write Stoffel a recommendation letter “acknowledging his reliable services as an artist,” which would be freely available to visitors to the biennial.

The artist’s conceit turned out to be more potent than the proposed work itself. In keeping with the generally taboo nature of discussion surrounding the rights of the Gulf ’s underclass of foreign maids and laborers, the biennial organizers declined to go along with Stoffel’s ruse. During the exhibition, he showed two panels of text — one a narrative explaining his concept and the outcome, the other a page from a local newspaper with advertisements placed by “sponsors” of Sri Lankans and Pakistanis who had “absconded from duty” and were therefore now outside the employer’s responsibility.

For Gulf-based biennial visitors, Stoffel’s project was audacious in its attempt to query the region’s strict racial and financial hierarchy of workers’ rights. (Since the biennial, new legislation has begun to address both the rights of the employee in the transferral of sponsorship and the prerogative of sponsors to impose the customary six-month ban — from the country, and/or from working for a competitor company — on some employees.)

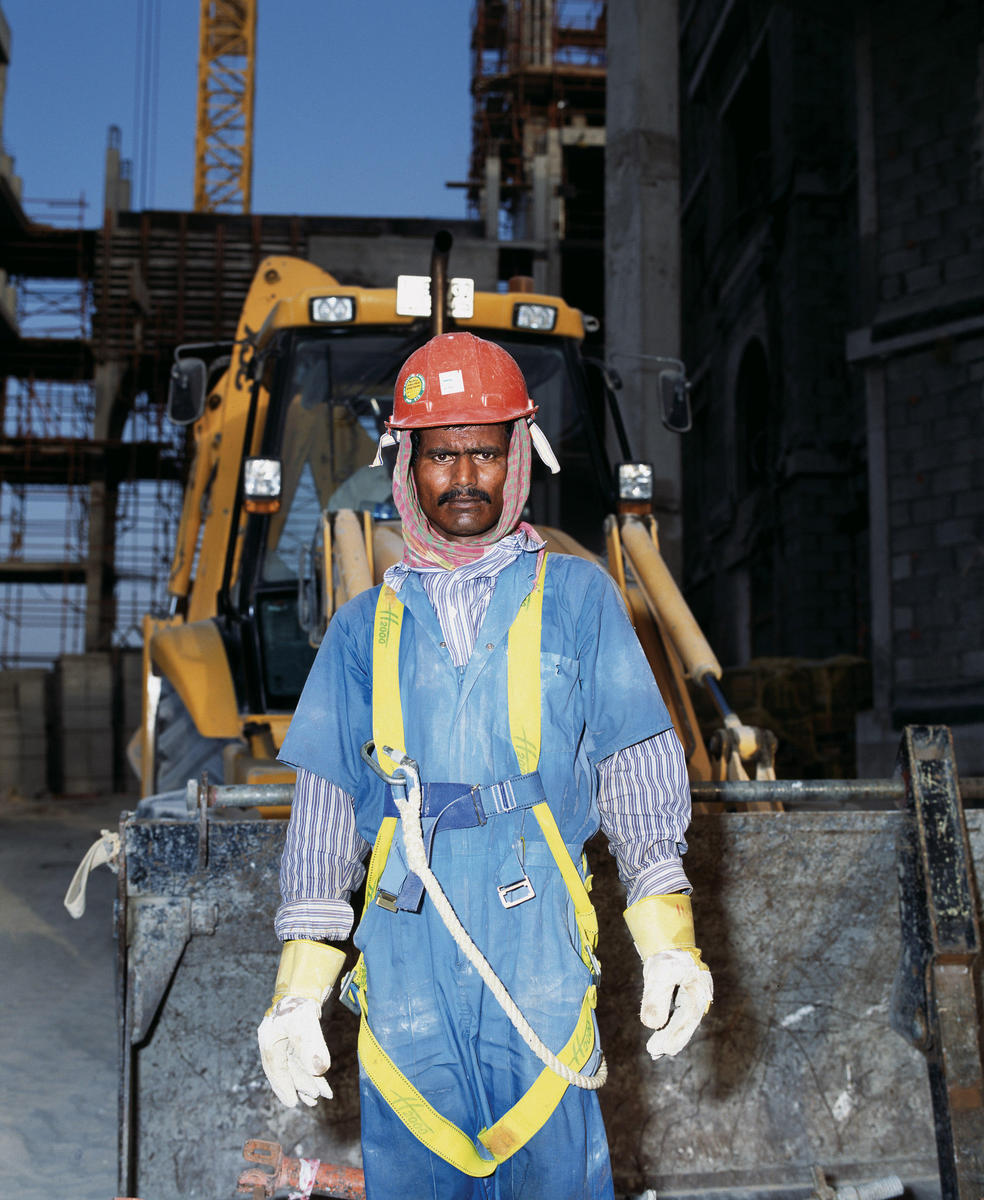

As he describes it, Stoffel attempted to establish a connection between the smallest minority in the UAE, that of the immigrant artist, and the largest, the immigrant laborer. (About two-thirds of the UAE’s work force comes from abroad, and about a quarter of all expats work as unskilled laborers for construction companies.) Stoffel concluded that the “two parallel lines of the biennial artist and the Pakistani worker never cross, and that is the paradox of the paradox: that even at an imaginary point, within an artwork, it’s impossible to establish a connection.”

Despite being the largest segment within the UAE population, the foreign working class remains by and large a faceless majority, known only to the wealthy minority through increasingly ballsy local media stories. Every week, the usually self-censoring UAE newspapers detail gory tales of trafficking, suicide, and rape; of false promises made by dubious foreign employment agencies and mounting debts; of dehydration while working in extreme summertime heat and humidity; of industrial accidents and loan sharks; of depressed, desolate labor camps. The Indian Embassy’s official list of its functions includes such grisly tasks as “processing applications received for providing free air tickets by Air India/Indian Airlines for transportation of dead bodies of destitute/stranded/ absconded Indian nationals.”

In many ways, the situation faced by the Gulf ’s legions of indentured laborers is mirrored worldwide, from Chinese cocklepickers in the UK to Mexican meatpackers in US abattoirs. But the particular state of affairs in Dubai, with its rapid growth and surface profligacy, takes a microscope to what’s vaguely termed globalization.

Even the most casual of holidaying sun-seekers, unversed in Naomi Klein, cannot fail to notice the twenty-four-hour building sites and the lines of identically dressed laborers waiting for dilapidated yellow school buses to ferry them to and from their crowded desert accommodations. The Consulate General of India in Dubai estimates that about 60 percent of the 1.2 million-strong Indian community in Dubai and the Northern Emirates, more than half of whom come from Kerala, are blue-collar workers who live in (what are unashamedly called) labor camps. The situation is floodlit by the contrast between, for example, the messy, raw process of building a five-star hotel on $100-a-month wages and the buffed exclusivity of the end result.

Equally hard to miss are the gangs of maids, mostly hailing from the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Indonesia, who mind Emirati and expat children, most visibly in parks and malls. The tradition of employing domestic staff is prevalent throughout the Middle East, but the volume of and reliance on foreign labor in the Gulf is astounding.

In a speech at the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas conference in January 2005, Shri Vinod Khanna, India’s Minister of State for External Affairs, highlighted the unique position of Gulf Indians. Numbering approximately 3.5 million, this group forms the “single largest interest group within the diaspora.” As “naturalization of aliens” is not permitted in the Gulf, they retain Indian citizenship; their earnings are homeward-bound and their wealth and property (and usually family) remain in India. Globally, remittances by foreign workers have doubled in the past five years; according to India’s Economic Times, Gulf Indians now contribute around five billion dollars a year to the Indian economy. (As expats are known to exclaim in cases of maidor gardener-guilt, “You know they go back to their villages as kings!”)

The minister noted the recent proliferation of Gulf government policies to replace foreigners with national workers (“Emiratization,” “Saudization” and so on), but it seems that this will have little impact on the need for domestic help or construction fodder — particularly in Dubai, which has one of the highest per capita construction spending rates in the world, according to the Middle East Economic Digest.

Permanent visitors, locked into a state of perpetual victimhood, the working classes’ poverty compounds their expat liminality. Many middle class Gastarbeiter enjoy the trappings of stakeholder status by engaging in communities, schools, and, since 2002, the capacity to buy property in selected areas. These days, wages may be no better than they are in their home country, though the lifestyle can be classic Country Club, and the winter weather kind. But the male-dominated foreign laboring classes aren’t permitted the same level of engagement with society. With their precious few fils flying directly home to their wives and children, they are divorced from the commercial hubs of a city where the mall is the majlis for the masses. Any sojourn in Dubai is an entirely transient, financial transaction.

It should be noted that within this invisible majority is huge diversity. The domestic workforce ranges from freelance cleaners, at the mercy of a “sponsor” who obtains their visa but does not necessarily become their employer, to supernannies with cut-glass references who are able to dictate the nationality of their employer and standard of accommodation and tickets back home. Many taxi drivers, multilingual and better traveled than the average gap year student, can indulge in urbane comparisons between taxi driving in Dubai, security guarding in Riyadh, and waiting tables in Bradford, for example.

When reading the horror stories, it’s easy to deny this amorphous mass of faceless workers their agency. Yet over the past year, a small laborers’ rights storm has been brewing in Dubai. Aided by an emboldened local press, workers have faced fears of deportation to confront construction company bosses who have denied them their salaries for months at a time. (Rather than take out adequate or further loans when in between mega-projects, these companies have squeezed the very bottom rung of the property ladder.)

The workers, even those whose companies have (illegally) retained their passports, have become cautious radicals, organizing sit-ins on Sheikh Zayed Road, Dubai’s main highway, and laying down tools in protest on the vast construction sites that pepper the emirate. In December 2005, thousands of taxi drivers followed suit in a series of strikes, refusing to budge until labor officials had promised to review rents, working conditions, and fine-based salary deductions. Now a subject of daily debate in the local press, the picketers’ plight has even started to creep into the international media, piercing a hole in the great PR bubble that is Dubai.

Spurred on by negotiations with the US over a free trade pact, and international pressure to conform to International Labour Organization standards, the UAE has begun amending its laws and has started to allow workers to set up trade unions. Even though many construction companies are ultimately owned by the Gulf ’s powerful trading families, the government has formed a committee to address complaints and promised to “name and shame” offenders. “We are very concerned about our country’s reputation,” Labor Undersecretary Khalid Alkhazraji said, tellingly. “If they [construction companies] don’t care about our country’s reputation, we don’t care about their reputation.”

According to the Indian Consulate, the UAE Labour Minister has given the go-ahead for a “workers’ city” to be built, and one Ministry-authorized agency established to exclusively supply Dubai’s 4,500 major contracting companies. In November 2005, Dubai Police initiated a “labor hotline” to deal with complaints; on its first day it received more than 1,300 phone calls from workers who hadn’t been paid their salaries.

While Peter Stoffel’s disappointment cannot be compared to the hardships of the average laborer, it says something that he found his status as an itinerant artist, traditionally privileged and above nationality and society, compromised and his biennial project curtailed. It’s more ironic that the UAE’s übervictim, the laborer, perhaps is doing more to influence society than the artist-intellectual, traditionally seen as the instigator of, or at least commentator on, change.

Stoffel found his project hampered by a system inclined to maintain the status quo. Likewise the clutch of Emirati artists participating in the biennial, including Hassan Sharif, Mohammed Kazem, Khalil Abdulwahed and Ebtissam Abdulaziz: unusually, their conceptual work critically documents the rapid changes within the UAE, but they are yet to receive the country-wide recognition and accompanying public debate that their inquiry deserves.