New York

Claire Fontaine

Reena Spaulings Fine Art

January 6–February 11, 2007

Claire Fontaine, like her notorious hostess Reena Spaulings, is a fictional artistic persona, the nom de guerre of a Paris-based duo, borrowed from a popular French stationery company. The women’s creation of their anonymous collectivity under an appropriated name both acknowledges the impossibility of artistic sincerity and attempts to resist the capitalist machinations of an art world that has successfully co-opted and exhausted the radical potentialities of past political and artistic avant-gardes. Their second New York show, Footnotes on the state of exception, presents a set of clever readymades that, while resisting didacticism, meditate on the continuing possibilities for effective political art, thought, and action in our contemporary moment.

These days, Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s notion of the “state of exception” is anything but exceptional in the art world. It serves as theoretical ammunition for artists, curators, and critics (myself included) of a particular political slant, when mounting attacks on the unchecked expansion of executive and state power that has accompanied the recent war on terror. Few, however, question the stifling effects this climate of fear, militarism, and compromised civil liberties — coupled with the pervasive control that capital and spectacle exert over our lives — has had on the efficacy of their artistic and political practice.

Acknowledging this political impotence as our inescapable common fate, Claire Fontaine creates self-reflexive works that draw from, yet also critique, the parallel histories of political and aesthetic avant-gardes and the tools, practices, and cultures of protest and resistance. A pair of objects cheekily applies Guy Debord’s radical strategy of détournement [diversion] to his own works. La Société du Spectacle brickbat (from 2006, as are all subsequent works referenced here), a brick encased in the cover of Debord’s revolutionary bible, counters the paralyzing disconnect between theory and praxis — often cited as the cause of the radical left’s eventual demise — by literally transforming theory into a practical tool for insurrection. Apple iPod playing Guy Debord’s Hurlements en faveur de Sade (1952) is just that, his 1952 film adapted for the revolutionary on the go. But is the resulting object an optimistic assertion that the radical message of past avant-gardes can be revitalized through new media, or a critique of the capitalist transformation of revolutionary zeal into mere entertainment, another example of Che t-shirt syndrome? In a similar vein, the romantic myth of heroic avant-gardism is subverted by Passe-partout (Chinatown, Year of the Pig), a set of custom-crafted lock picks whose potential as tools that challenge conventions of personal property and propriety is trivialized by the inclusion of kitschy key chains acquired in the gallery’s surrounding neighborhood. A fire is a fire is not a fire, a video loop that cycles through the combustion and reconstitution of a press photo of a burning car, questions the value of armed struggle; the tautology of both title and image speaks to the cyclical and self-extinguishing nature of revolutionary fervor and violent protest.

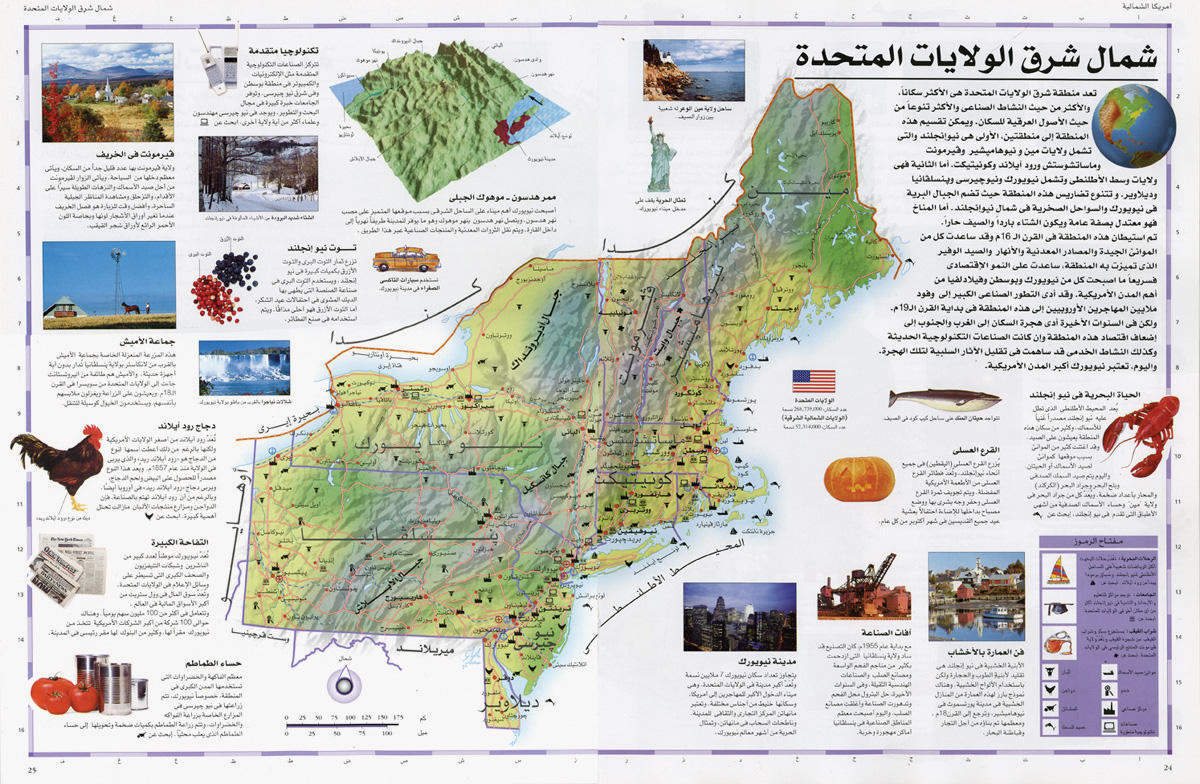

Suspicious of the integral role media and images play in the propagation of capitalism, much of Claire Fontaine’s practice centers on text. Ibis redibis non morieris in bello, a Bruce Naumaninspired flickering neon text wheel, spells out alternative translations of the titular Latin phrase: either “You will go to war, you will come back, you will not die” or “You will go to war, you will not come back, you will die,” both possible depending on where a comma is placed in the original. Disguised in the pulsating neon of spectacle, it strips away the discourses of patriotism, morality, and freedom used to justify imperialist wars and exposes war for what it simply and actually is, a life-or-death situation. The light box, another advertising tool, is employed in Visions of the World (France) and Visions of the World (New York, New York), encyclopedia-style entries in Arabic — with map, climate, flora and fauna, natural resources, landmarks, industry — of France and the Northeastern US respectively. These works recreate for French and English speakers the powerful sense of otherness and alienation that immigrants often experience as they navigate a new homeland, and the central role that language plays in this.

Created during a particularly incendiary period in French politics, marked by widespread rioting by Arab and North African immigrants in October 2005 and the anti-CPE labor protests in March 2006, many of these works tentatively hover between evincing a continuing commitment to protest and resistance and a growing cynicism toward the possibility of effecting change. This stifling hesitation is sketched out in the text of Dear R, a multi-paged, double-sided letter dated immediately post-2005 riots, presented as a neat stack à la Félix González-Torres, sitting atop a plastic carrier bag. A section of the letter recounts the story of a philosopher who sequesters himself, disheartened by the inability of his words to reach a broad public and make a difference. The parable serves as a critique of intellectualism and could certainly be leveled against Claire Fontaine’s own meta-political practice. But such a charge would misunderstand their works’ true political, if pessimistic, message, which is to reflect just how dire our political present is.