In the late 1990s, Egyptian American artist Amina Mansour prospectively mapped out the conceptual structure that she would fit her future body of work into. She modeled a conceptual container for her art, and has since worked within its boundaries. Her vast project has been presented to audiences in separate installments which she has called “Chapters.” The structure that ties these “chapters” together is actually a “hyperreal metanarrative” that is never revealed or directly mentioned. Much of the uncanny ambiguity in Mansour’s work is a result of her ability to discreetly hide the meta-narrative or regulate its presence to a symbol or a group of symbols within the work. The disarranged order further confuses the audience and serves to disrupt any linear or chronological readings. And yet, the simulated components that collectively form Mansour’s sculptures and installations actually do take on a progressive pattern, one that seems to be related to the concept of Darwinian evolution.

When taking into consideration the entire body of work the artist has produced as part of her ongoing project from its beginning until her latest solo exhibition, one can identify three stages of evolution. Mansour’s Cotton Sculptures can be said to represent the “protohistoric” period of her project: it is the stage of evolution were individual units are still in the early phases of development. The state of existence of the intricate seedling forms made out of pure white cotton could be compared to that of “primal selfish genes” — contained within square Plexiglas boxes, these seemingly protozoan forms have yet to form a consciousness of their own. When fully developed, these budding entities will need to inhabit a more sophisticated organism to survive. To visually render this ethereal existence and lightness of being, Mansour effectively uses a white-on-white color scheme.

In Vitrine (Chapters 1–5), Mansour’s calculated uncovering of her subject matter is an attempt to render a bicultural and historical junction. Mansour leans towards a “new historicism” as she deconstructs the histories of the two cultures she relates to the most: the American Deep South prior to the civil war, and the Mediterranean metropolis of Alexandria, Egypt, prior to the 1952 revolution. The artist relocates the fragments that have been produced during the deconstruction process, using them to create a sculpture rich in metaphorical and symbolic meaning. She capitalizes on the fact that aristocratic cotton-trading families in both cultures shared some similar tastes and sensibilities. The darkly veneered Louise XV vitrine represents the kind of objets d’art and refined furniture one would find in the homes of such families. The juxtaposition of the two cultures is evident in the oval shaped, hand-painted porcelain plaque embedded in the middle of the vitrine. A drawing that depicts an American antebellum home centers the plaque while the names of prosperous, cotton-trading Egyptian families are inscribed on the plaque’s slightly protruding surface. The European sounding names show that cotton trading was mostly an expatriate business, which was also the case in the United States. By replacing the slender tubular legs typical of such furniture with muscular female legs carved out of wood — which rest on elegant but claw-like hands — Mansour is perhaps evoking metaphors for the relationship between the working class and the privileged traders. The cotton floral bouquet, which is the centerpiece of the vitrine, suggests that the seedling forms of Mansour’s earlier pieces have evolved into multi-cellular organisms; they have inhibited what Dawkins would call a “survival machine,” and, although still locked up inside an airtight space, they have developed some sort of volition. The dialogue between the developing inner will of the cotton flowers, and the enclosed patriarchal fostering the vitrine provides for them, gives the piece a lethargic atmosphere.

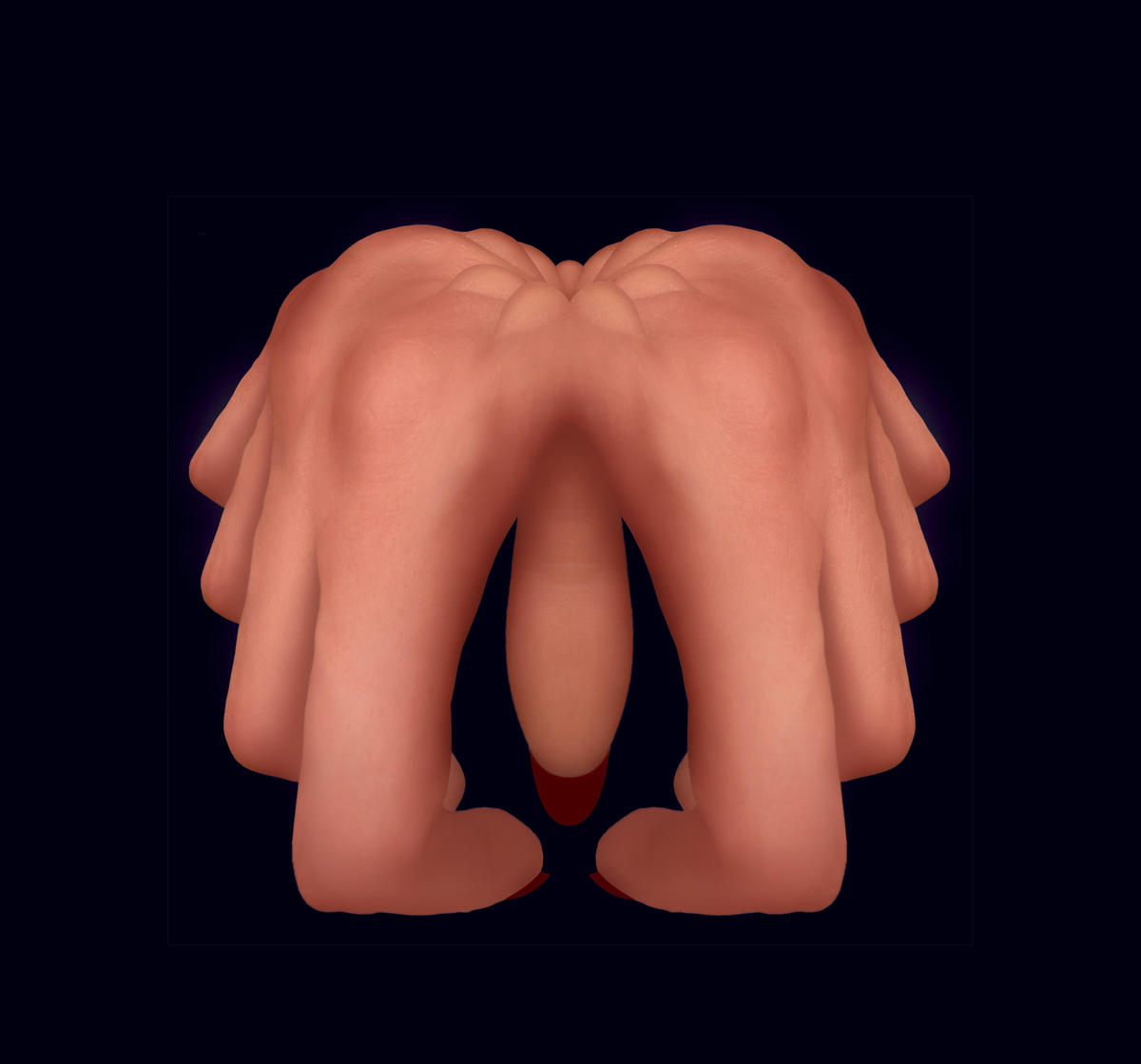

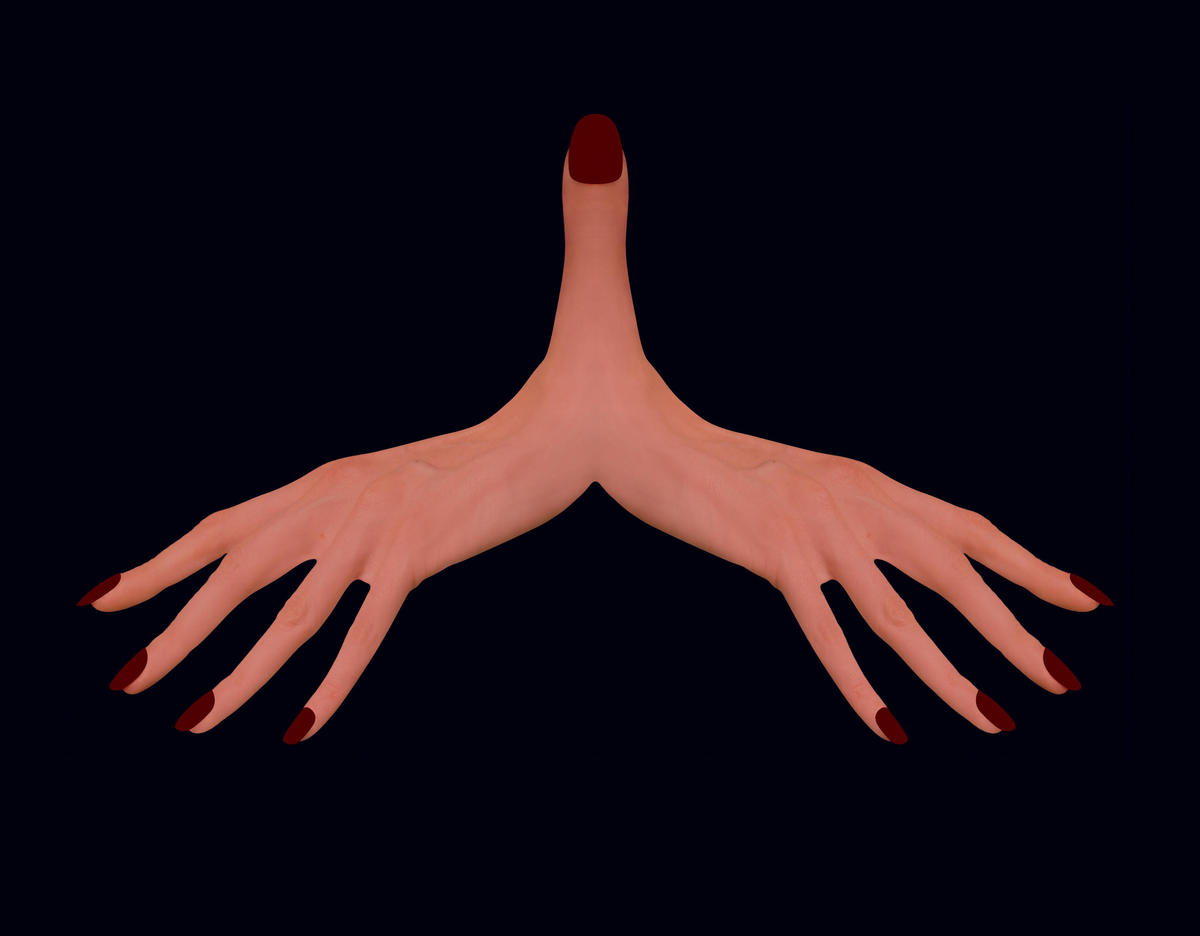

Mansour’s latest installation, Chapter 15: A Failed Contemporary Attempt at Being a Modern Day Ophelia — specially conceived to fit into the enormous empty space of a rundown factory — pushes the evolution of the organisms a little further. Here, the floral entities of the past projects have developed into quasi-human organisms formulated from images of female hands. These computer-generated hand symbols signify a peculiar sign language that seems to be communicating the organisms’ newly-found will. Although they seem androgynous, what appears to be recently developed sex organs make their first appearance in Mansour’s project, implying a need for movement after a long span of directionless existence. What makes Mansour’s work so perplexing is that even if the need for life is expressed in the evolution of the organisms, it is always counterbalanced by the tragic aura of death lingering in the narrative.