On March 14, 2005, just one month after the assassination of Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, over one million protesters gathered at a space called Martyrs’ Square in downtown Beirut. They assembled for various reasons — mainly to demonstrate their opposition to the Syrian occupation of Lebanon, as well as to protest that country’s alleged involvement in Hariri’s assassination. Though the assemblage did not (and could not) reflect the opinion of every Lebanese in the country, it was a testament to the power of place in serving as a collecting ground for a movement. The assembled gave that space, situated just on the Mediterranean waterfront and straddling the green line that divided the city during its decades-long civil war, a new name, dubbing it (romantically, no less) “freedom square.”

On that March day, architecture, through the space it created around it, coupled with the words of the protestors, arguably played a role in rewriting Lebanese contemporary history. Architecture became palpable through its absence — in other words through the void of the square.

Ironically enough, only months before, the square had been the subject of an international urban design competition organized by Solidere, the private company charged with much of the reconstruction of downtown Beirut. In November, just two months after the Israeli aggression on Lebanon came to an end, New York-based architect Makram elKadi of the international design firm L.E.FT engaged the winners of the Martyrs’ Square competition, the Greek team of Vassiliki Agorastidou, Bouki Babalou-Noukaki, Lito Ioannidou, and Antonis Noukakis, about the meaning of the formidable task that lay ahead of them. Can one even speak of an exalted reconstruction in such uncertain times? What role can and should design play in the future of Lebanon, and what of the possibilities of public space? Whose space is Martys’ Square, anyway, and is inclusion — the creation of a truly national site — a realizable task in the first place?

Bouki Babalou-Noukaki, a member of the winning design team and professor of architecture at the National Technical University of Athens, took on the following questions.

Makram elKadi:Is it legitimate or contested to have “outsiders” — in other words, Greeks — preparing these plans?

Bouki Babalou-Noukaki: The design of such a project from a non-local team of course has the disadvantage of lacking the actual lived experience of the place. On the other hand one might say that a distant and less involved and sentimental position can be an advantage in applying design ideas from a more “global” point of view.

One thing we can say about being Greek is that we are familiar with spaces in which there is a multiplicity of layers. We’re also familiar with recent civil conflicts — which in the case of Lebanon, is a sensitive piece of its history still very much haunting public life.

MeK: As a Greek team, where did your interest in the project come from in the first place, why Beirut?

BBN: We share the same sea — the Mediterranean — so we are accustomed to the environment. The sea, antiquities, places charged with memories of struggle, conflict and reconciliation are elements that are also familiar to us. We felt that it would be a challenge to deal with sensitive issues tied to these complex and multilayered histories.

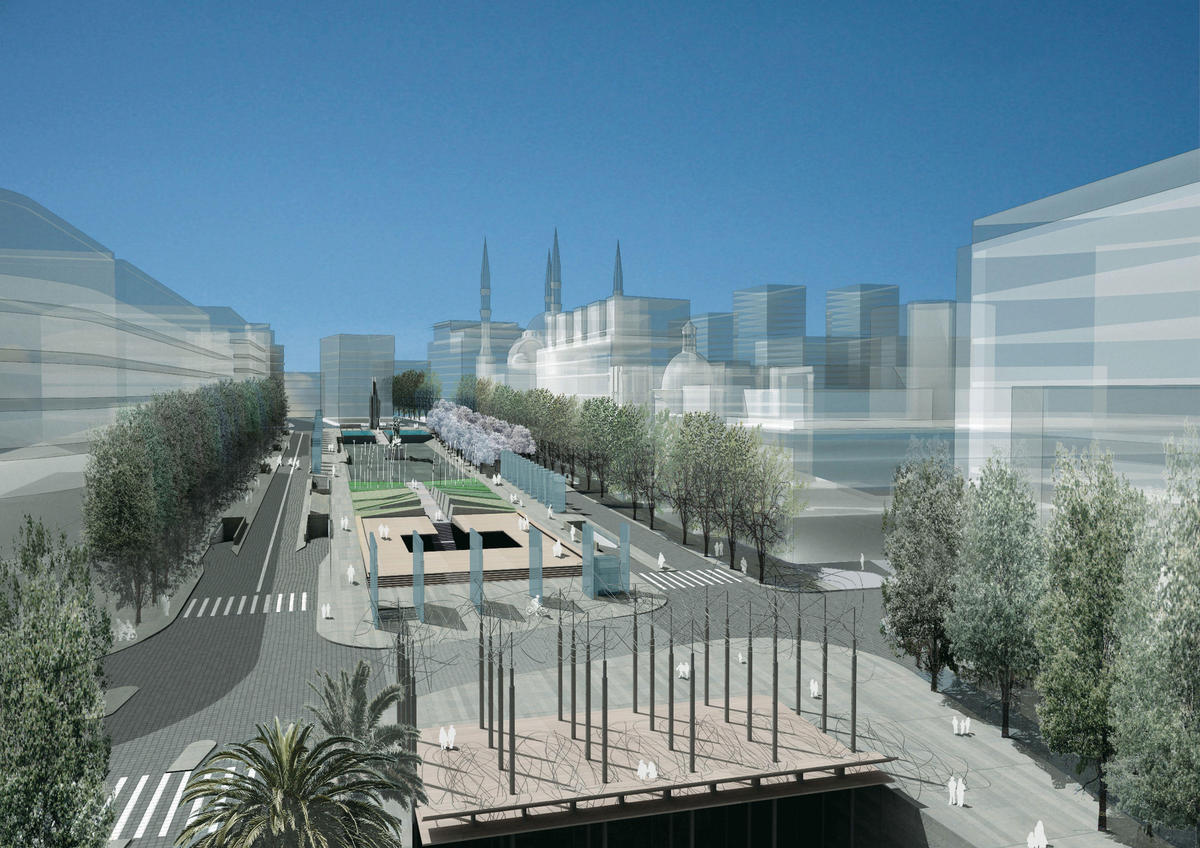

We considered the city a palimpsest on which historical layers are engraved. So in the case of a spatial intervention, these layers needed to be read and reinterpreted. Our main concept for the competition has been the revealing of historical layers that compose this space. We’ve introduced the idea of a “fissure” on the city surface that tears the earth into two fragments only in order to reunify it. This fissure is constantly transformed while the axis evolves, creating a continuous route towards the sea — organizing urban space in a sequence of “episodes.” Four “topoi” define the axis: The “threshold” symbolizes present time and is about intensity, rhythm, contemporary city life, communication, information. The “memorial void” represents the recent past and is about reflection and pause, but also tension and protest. The “trench” represents history and is about tranquility and a common past. The “gateway to the sea” symbolizes the remote past and is about reverie, recreation, and journey. These distinct places play different roles in the narrative of the entire area.

MeK: The site is charged and polarized with political undertones, from the Ottoman period, passing through the civil war, up to the events of this past summer. How did your proposal respond to these historical conditions? Can and should urban design be neutral in such a loaded political context?

BBN: The concept of the project is rooted in the unfolding of the historic layers of the city. The different historical periods are gradually revealed. For example, we use the foundations of the Ottoman period Petit Serail to attempt a literal descent from everyday city life through the ancient ruins to the Phoenician port. As far as the recent history is concerned, we think that the past could be expressed and memorialized in space as an attempt to gradually push it into the collective memory. At the same time, the space should be open and available for people to reclaim it, reoccupy and redefine it.

MeK: As architects, how did you address the green line, the demarcation line that separated the predominantly Christian east Beirut from the predominantly Muslim west Beirut, a line that passes through Martyrs’ Square to this day?

BBN: The concept of the fissure is a symbolic expression of division, but it also marks the simple promenade towards the sea. At the same time, the fissure acts as a “stitch” between the two bounds of the city.

The two parallel roads (east and west) have isolated the square from its surrounding context, turning it to an “island.” To reinforce the spatial unification we proposed the pedestrianization of the west road and the narrowing of the east road. The two fronts of the city become related through their in-between space. Martyrs’ Square has a meaning as a place along an axis as well as a link between the historical center (west) and the new central area (east).

MeK: What urban knowledge can we gain from the events of March 14, 2005 — when thousands assembled on the one-month anniversary of the assassination of Rafik Hariri? What are the implications of that knowledge on your plans, if any? On that day, the void of the square proved to be its most significant asset. How did you design the new void of the square? Is it one void or several?

BBN: Martyrs’ Square is inscribed in the collective memory as a common space for public concentration. The events of that March confirm that the main square “Memorial Void” should be an actual void — not only as a functional gesture, but more urgently as a symbolic one. It should be able to receive crowds and be a place for action and democratic expression. The “Memorial Void” is a void within the void of the Grand Axis of Beirut.

MeK: How does one deal with memory in a city like Beirut in which memory is constantly being recreated, and when history itself is debated and debatable?

BBN: The design of public space should create opportunities to continually redefine the identity of the city. The revelation of the historical layers of the city reinforces the notion of a common past, and is a part of that process of redefinition. We feel that expressing and memorializing the past in space should be a process that generates public discourse — which is, you could say, one of the first steps in coping with a traumatic past.

MeK: Your plans take into account the future of a museum. What kind of museum will this be, and who will get to decide the contents and curation? Isn’t it incredibly loaded to put such a political institution in a public space? Could it not be divisive/contested?

BBN: Generally the important public spaces of a city usually coincide with cultural and public buildings, which also contribute to the character of the city. The museum proposed for the competition is a site museum articulated next to the antiquities. It functions as a common information center about the history of the place, reinforcing the promenade — floating through the historic layers of the city. The museum space functions as an episode in the pedestrian flow.

MeK: Given the turbulent past and present of the country, is it absurd to think of “reconstruction” after the most recent war? What role can architecture and urban design play in this picture?

BBN: This is a hard question. One thing to be said is that we value and admire the Lebanese people and their Sisyphean efforts to rebuild their country. We want to believe that the completion of an architectural design work with the significance of Martyrs’ Square would bear a symbolic importance — perhaps even more than a tangible one.

The destruction of the reconstruction — the death and the birth — constitute the perpetual circle of life. Violence works as a catalyst creating extreme situations. The role of architecture and of urban design is to accommodate and shape historical events, to formulate places of memory but at the same time generate new frameworks for the future.