Dubai’s ubiquitous advertising billboards are stage sets that promote the desired personality of an enviable promised land, a place of opportunities where dreams can come true. The embodiment of Guy Debord’s seminal study, The Society of the Spectacle, the city is defined by fantastic dreamscapes that rise from the shifting sands of the desert and are continually remodeled in line with the visions of its chief architects. Its visual communications media — fascinating case studies in cultural production or construction — scream their messages to the city’s residents in superlative slogans. They instill in the people’s psyche an emotional impulse, a brand that goes beyond the product — the city and the lifestyle it promises. Through their individual designs (using symbols, colors, typography, and visual messages), they collectively define the city’s global sense of place, its investment in its perceived image. Dubai boasts about its future creating greater and greater distance from its past. It responds to its changing demographics and, therefore, to its need to align itself with the global community of affluent societies. The Dubai brand becomes the means to create a coherent culture that unifies, and defines, the city’s residents — people with otherwise little common cultural or linguistic heritage.

That Dubai has chosen this straightforward, American-style marketing strategy for its image development comes as no surprise for a city with global aspirations. The Dubai brand is built upon a simple narrative and a universal, emotional concept. Its value system is one that can be appropriated with ease. Dubai today is the Middle East’s most successful and liberal business model. The city prides itself on being a shopping destination — even hosting an annual Shopping Festival — and is developing ever-larger theme parks that transform entertainment into a commodity, sedating its growing population of young, affluent professionals.

What defines Dubai’s character? Is the city simply ruthless, extravagant, and full of the entrepreneurial ambition of youth? Or does it strike a balance between progression and tradition?

A critical examination of Dubai’s environmental graphics and its monumental advertising billboards offers a telling picture of visual landmarks that define and promote the city’s image. Dubai is usually presented as a concentration of architectural developments and myriad construction sites. But for me, the landscape — and the population’s collective consciousness — is defined by its peculiar penchant for megalomaniac graphics and quirky typographic messages.

A long parade of logo — symbols representing individual corporate tribes — declare their allegiance to the king of the pack, the government-owned umbrella “company,” Dubai Holding. One billboard extends for about a kilometer, stating its motto, in bold red: “For the good of tomorrow.” The “tribes” belonging to this mega multinational company are an unlikely mix of entertainment, technology, media, health, charity, education, business, and real estate developers. Dubai Holding’s logo is loaded with optimism, and portrays the ruthless and adventurous city at its best. The logo’s ability to blend into and subvert pre-existing identities can be interpreted as a fair representation of the city’s character and its political aspiration to assimilate itself into the world of tomorrow. The swoosh that dots the “i” of Dubai is a universal mark, here standing for “good” and “go ahead” and “the right choice.” Its red color is energetic and memorable; its tick-like angularity resembles the sharpness and hardness of diamonds; and its placement over the word “Dubai” gives the impression of a gem’s sparkle under the light. Dubai Inc is branded as a commercial “gem” proudly shining under the blazing sun of the Arabian Gulf.

Other government-sanctioned projects, advertising and PR companies — of which Dubai boasts a plentiful supply — have relied on a convincing mix of minimalist, international, and business-like visual styles, and the sober colors of navy blue and silver, and diamond-shaped symbols alluding to the Islamic art tradition. Dubai Properties’ logo, for example, references wealth and success (diamonds), as well as Arabic calligraphy (the oblong-shaped dot often placed on top or below some of the letters of the Arabic alphabet). The Dubai International Financial Center (DIFC) branding, meanwhile, is a strange mix of Wall Street aesthetics and an arabesque motif, constructed within yet another diamond-shaped symbol.

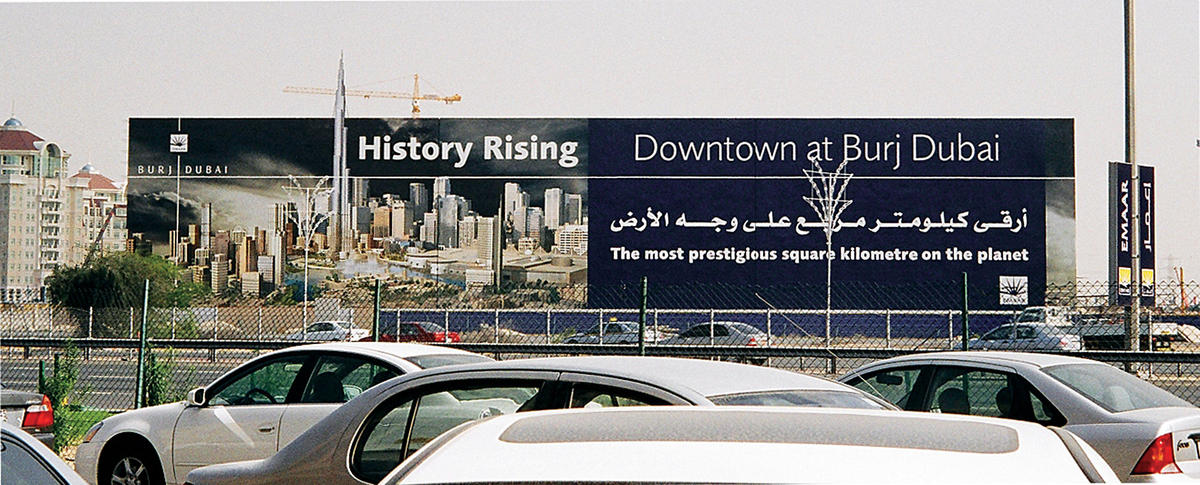

Humongous billboards, spread all along Sheikh Zayed Road, promote Dubai’s ambitious building projects and compound the image of a city obsessed with grandeur and wealth. The billboard for Burj Dubai, predicted to be the tallest development in the world, defiantly declares the project “the most prestigious square kilometer on the planet,” where “history” is re-invented and “rising,” as if by sheer miracle, from the flat, desert floor. The billboard announces an idealized business dreamscape of the third millennium, in all its glory and fanfare, its skyscrapers reaching towards the sun, like steel-and-glass plant-forms of a futuristic world. Slogans occupy more than half of the billboard’s space, taking a pronounced precedence over the image, and allowing only a small and thin tip of the highest tower to break out of its physical confines.

This “gem” of the desert, however, has not totally abandoned its historical origins: just as desert dwellers obsessed over water and greenery, Dubai’s new identity is tied to the sea and futuristic, artificial lakes and rivers. The branding of Business Bay — a business park located along the waterfront of a man-made creek — can be read as an expression of cultural heritage. The archetypal Islamic architectural element of bringing water (pools and fountains) inside the home or palace is the ultimate manifestation of luxury in the arid desert environment. In the new, grandiose Dubai, the traditional pool becomes a whole bay or creek.

Dubai’s projects are a never-ending reinvention of reality; land is replaced by water and water by land. The city’s fixation on the forestation of the desert has gone beyond the usual planting and diligent maintenance of trees and plants. Employing that hackneyed Arabian emblem, the palm tree, the emirate has created tree-shaped islands, large enough to be seen from outer space. The logo employed by development company Nakheel for the projects is elegant and natural: Its choice of color invokes the pleasant calming colors of nature (blue for the expansive sea and green for the fresh and clean air and flora); its shape of waves and leaves are those of the Arabian garden. These islands represent the poetic luxury of seclusion, the escape from the straining reality of modern life; they are protected from the sea by a ring of “water homes” arranged to form the shape of a line of calligraphic poetry written by the emirate’s crown prince, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum. The three Palm Islands — plus The World, a fourth group of islands fashioned in the shape of the continents — physically and metaphorically do, as the slogan goes, “put Dubai on the map.”

Dubai Inc’s defiant, proud posturing and its extravagant impulses are expressed through its plethora of shopping malls as well as its architectural follies. Brimming with youth and vitality, and in daring pink, a celebratory image of Burjuman mall promises consumers “luxurious shopping and incredible rewards;” whole skyscrapers along Sheikh Zayed Road announce the juicy, sexy messages of cosmetic product advertising.

This reference to luxury is taken to an even higher level of sophistication, craft, and attention-to-detail in the Disney-like new “shopping city,” Madinat Jumeirah. A pastiche of traditional architecture, at (of course) a much larger and grander scale than those of the existing souks and modest Arabian houses of the “old” Dubai, Madinat Jumeirah announces itself with glittering gold and blue mosaics of fancy Arabic calligraphy. An intimidating fortress gate with symmetrical decorative towers reminds consumers of the privilege of admittance to this ultimate shopping and entertainment paradise. Madinat Jumeirah’s logo is a playful dance of letters that twirl in a circular disk, like a delicious meal offered on a golden plate rimmed with diamonds, representing the complex’s luxurious retail experience. Meanwhile, the geometrical logo of the Souk Madinat Jumeirah conveys the opposite: a structured order resembling an architectural map of the Arabian house, arranged around an inner “secret” courtyard. The two logos stand as testimony to the nature of the visitor’s experience of this “city” where one is lost among shops and goods of all kinds, where luxury is expressed through every retail outlet’s brand identity, and where the diversity is held together only by the overall feel of well-crafted design. Even the most mundane traffic and parking signs are mounted onto elaborately carved, painted and branded wooden poles. After all, the alleys and inner courtyards of this contemporary souk are defined by an organized chaos and curbed sensuality.

Every aspect of visual representation in Dubai has a claim on luxury, richness, and abundance; the emirate’s brand identity is a strange medley of Wall Street and Disneyland, of American and Arabian symbolism. Dubai represents itself as the ambassador of the future Arabian umma, making its daring and bold steps towards a self-conscious new world order, defined as much by marketing as by reality.