New York

Emily Jacir: Dispatch

Alexander and Bonin

October 28–November 28, 2009

In writing about Emily Jacir’s Where We Come From (2001–03), Edward Said remarked upon one of the most salient aspects of daily life for a Palestinian: the waiting. There is the waiting at checkpoints, waiting for papers to arrive, waiting for visas to be granted or refused — “eons of wasted time, gone without a trace.” A Palestinian from Lydda can never return there, Said wrote, because its inhabitants were evacuated by Israelis in 1948, and the town was renamed. Jacir’s work, in which she carried out and documented the wishes of displaced Palestinians who could no longer access their homeland, lyrically gave form to the interminable wait, and called attention to its paradoxical nature.

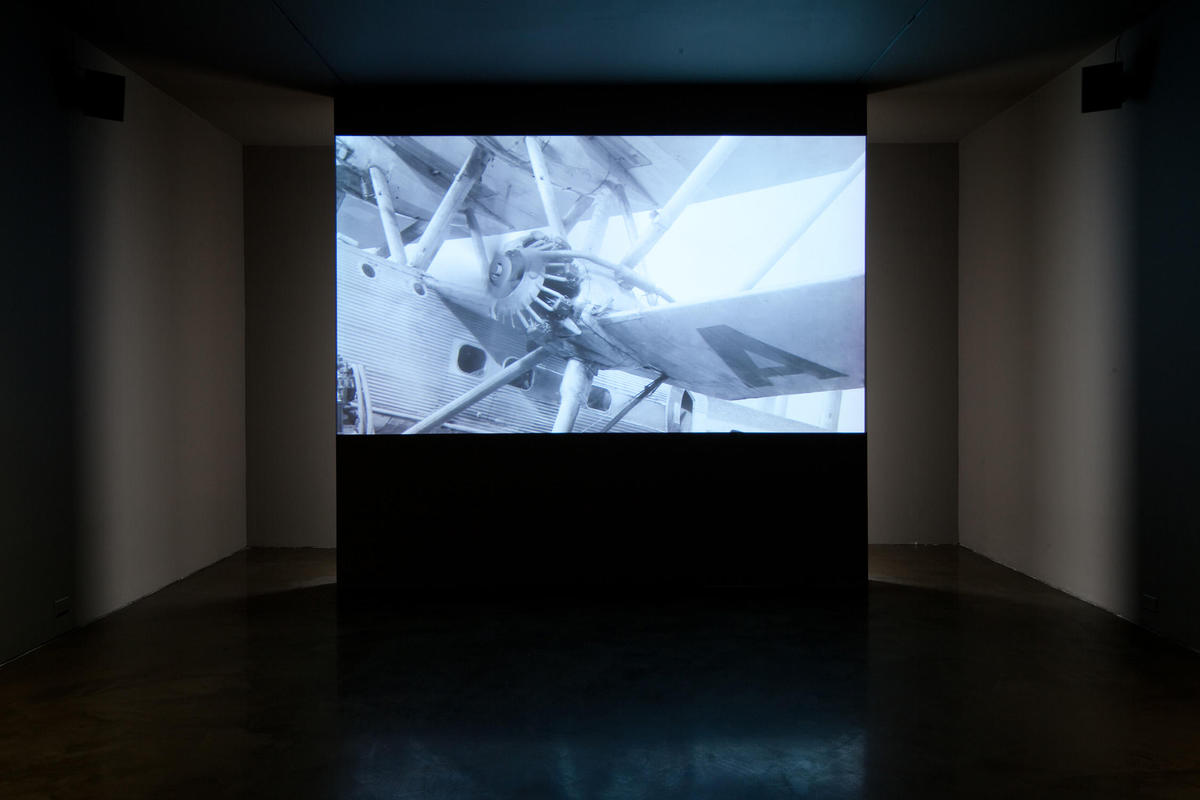

Lydda Airport, one of two projects in Jacir’s recent exhibition, ‘Dispatch,’ returned to Said’s invisible site by way of film noir. The exhibition’s central work was a short black and white film. Archival photographs of the airport circa 1936 were animated into a narrative involving concrete runways, Jacir herself, and a dashing clunker of a plane emblazoned with “Palestinian Airways Limited.” Lydda Airport was to be a stopover for Imperial Airlines in the British Mandate of Palestine. A scale model of the building stood in a separate gallery, showing off a curved central tower flanked by descending tiers of elongated horizontal masses: a typical example of modernist architecture for export — international style with a touch of De Stijl utopianism. As an object, the architecture was an anachronistic blueprint for a future that never arrived. Captured by Israeli forces in 1948, Lydda Airport is now Israel’s Ben Gurion International.

As the plane in the film silently took off, there was a closeup of a woman’s eyes, a crackle of paper, and a view of a bouquet of roses. Amelia Earhart, Jacir’s story went, was to have been welcomed to Lydda in 1937 by Edmond Tamari, an employee of a Palestinian transport company. “She never arrived,” a press statement confirmed. But Jacir’s silent, smiling figure, played by the artist herself, wasn’t quite the same thing as Earhart’s hapless greeter. Hovering about the half-finished airport structure, she looked weirdly disjunctive, like a time traveler on the lookout for a history that hasn’t arrived either. Set on a continuous loop, her waiting seemed more interminable with every repetition. The film was a playfully self-reflexive departure for Jacir, whose conceptual armature is usually much more conclusive. What the fragmentary narrative lost in directness, it gained in poetry and open-endedness.

Said would probably have enjoyed Lydda Airport. The late critic was an admirer of the elegance and clarity of Jacir’s work, and he undeniably agreed with her politics. But Jacir’s meteoric rise, marked recently by major awards from the Venice Biennale and the Guggenheim Museum, has invited widely diverging critical responses. On one side, there is lyrical praise — of how her work’s “simplicity could make you weep,” how it expresses “the ache of things undone” — readings that appear overwrought in comparison with the economy of Jacir’s conceptual gestures. Her detractors, of course, can be just as excessive. “Dry, cerebral, fragmentary and stylistically derivative,” snapped the New York Times of her recent Guggenheim exhibition, concluding that “the problem is with her unexceptional artistry, not her politics.” Ouch. Time Out New York set the all-time low, though, with intimations of evil festering in the aesthetic soul. “It is not the museum’s business to help this Palestinian further her cause,” a patron had complained to the Queens Museum several years ago. Institutions now preface her work with the museum’s political equivalent of parental advisory stickers.

Does the provocation lie in the affective impact of the work, or in the uncompromising nature of Jacir’s politics? One could well ask the same question of her supporters as of her detractors. To admire Jacir’s work presumes a sympathy with its issues, an openness to the histories therein, and a responsiveness to the poetic forms used to express them. At an institutional level, she’s doubtless considered useful, addressing token ideological ethnic questions. But in the absence of such receptiveness or requirements, wouldn’t such work usually be ignored? Not in Jacir’s case. stazione, the second project in the exhibition, was yet another example of authorities moving to suppress her work, in this case, without its even having been publicly displayed.

stazione was a series of photographs and a brochure that comprised Jacir’s proposal for the 2009 Venice Biennale. She had planned to add Arabic translations to the names of the vaporetto stops on the route that winds down the Grand Canal, drawing attention to Venice as a historic “station” for cultural exchange between Europe and the Arab world. The photographs were mockups of her proposal, where Ca’ d’Oro, for example, was accompanied by its literal translation into Arabic, bayt az-zahab. The intervention would have been a modest, if very visible, one — surely one of the less dramatic public sights during the tourist season of the biennial. But the wall text at Alexander and Bonin informed us that the work was “abruptly cancelled by Venetian municipal authorities and remains unrealized.”

It was tempting, given Jacir’s history, to take this as further evidence of how her art can rattle the powers that be. But if the Venice municipality was nervous about accusations of aesthetic evil or anti-Semitism, the installation at least gave no hint of that. The censorship marked stazione with a peculiar, indefinable aura; I couldn’t help but scrutinize the photos for possible offenses, trying to imagine the sinister and shocking impact of Arabic text upon… the international art world? Its motivations notwithstanding, the Venice cancellation established parallels between stazione and Lydda Airport, and their reference to Palestine itself: as sites of forgotten histories and, finally, as unrealized propositions.