Beirut

Exposure 2009

Beirut Art Center

April 22—June 9, 2009

One of the photos in Karine Wehbe’s Tabarja Beach 1 (2008–'09) captured a vista of Lebanese nostalgia. Two young women sat poolside: One looked into the camera, like anyone who’s just noticed she’d being observed; the other, oblivious beneath her headphones, stared blankly into the distance. As with so much Lebanese visual culture, the photo’s strength resided in its incongruities. The poolside umbrellas were skeletons. Long-drained, the pool had begun to collect the empty bottles and wind-blown sand of dereliction.

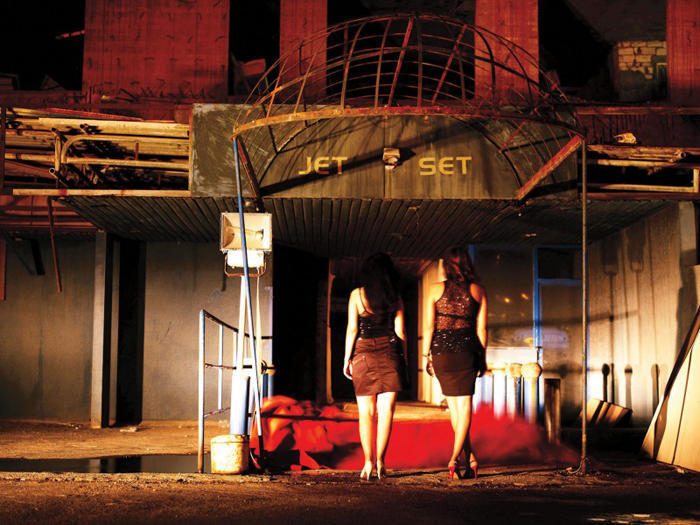

Wehbe’s work was her contribution to ‘Exposure 2009,’ one of two exhibitions up at the Beirut Art Center this past spring. Though her photos weren’t all equally affecting, all were unified by a sense of opulence gone to seed. In her notes, she tied her locations to an adolescence in Lebanon at the time of the civil war — when the destruction of the downtown and the dangers of traveling between east and west transformed Beirut into archipelagoes of nightlife surrounding a ruined core. With the return of peace, affluence abandoned these islands. The success of this photograph lay not in its evocation of the quotidian but in its speaking to a wider narrative of the obsolescence that slumps in the shadow of development.

‘Exposure’ wasn’t a typical curated show. It was the first installment of a yearly event dedicated to emerging local artists who are invited to present new works, or works that are new to Lebanon. Selected on the strength of project proposals rather than thematic consistency, ‘Exposure’ was less informative about the state of art in Lebanon than it was about individual artists. That said, some of the more interesting work in the show shared, with Wehbe’s, a sublimation of the past.

Perhaps the best-realized piece in ‘Exposure’ was Raed Yassin’s 2008 installation The Best of Sammy Clark, which contrived a fictive genealogy linking the artist to a singer of the war era. If the success of Wehbe’s work resided in the melancholy irony framing an ephemeral gilded age, Yassin’s piece resonated with pop culture’s extravagant amplification of the ordinary.

Enclosed within a bright green and pink room, Yassin’s installation comprised several components. Confronting spectators entering the room was a wall-size text (the English-language exhibit tag writ large), a distinctly Maoist invocation of the erstwhile pop star’s memory. At the center of the room were four turntables, each playing a different Clark LP. Peripheral walls were lined with clusters of photos, packaged in 70s-era florescent frames, of Sammy Clark entertaining the artist’s family during a birthday party. Clark’s mentoring role was evoked in a series of autographed LP covers. Their dedications — “For Raed / The miracle child / And the artists’ hope / For you the most beautiful songs / Sammy”; “For Raed / The major in the Lebanese army / The villain’s fighter / For you this national album / Long live Lebanon / Sammy” — were replete with ironic gestures toward nationalism and celebrity.

Thirty-year-old Yassin is arguably outside the debates over historical erasure that have preoccupied an older generation of Lebanese artists. Less interested in Beirut’s cult of the reanimated corpse than the trash culture that litters its grave, The Best of Sammy Clark was redolent of the fetid air of Lebanese civil war nostalgia, whose cloying odors evoke contemporary popular culture as well as pop culture past.

Before Dark (2009), a 150-second animated video by the thirty-two-year-old, Beirut- based Kuwaiti artist Tamara al-Samerraei, echoed another narrative of genealogy and disenfranchisement, though its cadences lacked the Lebanese dialect’s ironies. The scenario showed a little girl — echoing the prepubescent waifs who populate Samerraei’s canvases — running up the Malwiya, the ninth-century spiral minaret that the Abbasids built in the Iraqi city of Samarra. There, according to the artist’s notes, Caliph Al-Mutawakkil had personally escorted his muezzin to the top of the minaret on his donkey.

The shadow of a donkey followed the girl to the top of the tower. A local metaphor for human stupidity, the donkey lent her ascent a Sisyphean quality, reiterated when she reached the top of the tower and seemed to knock her head repeatedly against the wall. Atop the minaret, the girl’s oversize silhouette turned on an axis, a silent muezzin calling to (or an unlit lighthouse lamp warning off) the absent object of her quest. Samarra — the ancestral home of the artist’s family — is a city heavy with metaphor. The effect of placing the girl’s playful labors there was not to make Before Dark geopolitically topical but to render it archaeological.

To cross the floor from the left side of the BAC gallery to the right was to pass from the silence of ‘Exposure’ into the cacophony of ‘4,’ an exhibition of video and sound art funded by the European Cultural Foundation’s ALMOSTREAL program.

Kinda Hassan’s three-channel video installation Ashoura–Untitled (2007) took the observance of the Shia Muslim commemoration of the death of Imam Husayn in the Lebanese village of Nabatiya as its point of departure, exploring how it is used as an opportunity for young men to perform manhood rituals for an appreciative female audience.

The Sea Is A Stereo was the latest incarnation of Mounira Al Solh’s ongoing video/ photo installation, a playful subversion of the representational-factual premises of documentary practice that examines a group of Lebanese men who regularly swim in one of Beirut’s still-undeveloped stretches of Mediterranean seafront.

Charbel Haber’s When No Body’s Around (The Cables between us) (2007–'08) was a sound installation for eight electric guitars. The composition rumbled through speakers in one room, while, in another, the guitars were bowed silently by primitive machines. The piece’s stated purpose was to maintain the hoax “that this city is inhabited,” making it allusive of both the conceptual concerns of an older generation of artists and the more mundane apocalypse of contemporary youth emigration.

While all the works were intriguing on their own terms, Cynthia Zaven’s twenty-six-minute, eight-channel sound installation Octophonic Diary (2007–'08), housed in an isolated blue-lit room, was the most accomplished. Though it contained long passages of conventional composition, in the arrangement of individual notes Octophonic Diary was a meta-composition. Excerpts from Zaven’s pieces for piano and cello were mixed in among other discrete components of sound, providing a kind of counterpoint in multiple voices. The piece carried the listener through gauzy aural topographies. Schoolchildren sang; a vocalist practiced scales. A record player’s needle rode an LP’s dead space. A bomb detonated, keys were inserted into a lock, a ticking clock resolved into a clacking manual typewriter — the samples were organic rather than manipulative or contrived. Strewn among archived fragments of performance, they echoed through the darkness that inspired, or conspired, against the creative act.