London

Francis Alÿs: A Story of Deception

Tate Modern

June 15–September 5, 2010

What happens when everyday acts go undocumented or are simply forgotten? How can we bring into view multiple economies, when what is primarily visible in the world is dominated by a single economy? What could an art practice that is based on walking, collaboration, play, rehearsal, and re-enactment look like? Why would one ever leap into a tornado in order to film it? The latest solo show of Belgian, Mexico-based artist Francis Alÿs, which impressively brings together over a decade of work, might begin to provide some answers. Covering a large space on the first floor of the Tate Modern and spanning a labyrinth of sixteen exhibition rooms, Alÿs’s show was a marathon in itself.

Comprised of small, enigmatic paintings, rough sketches, simple but evocative videos, an animation, installations, personal post-it notes, newspaper clippings, and the stuff of a considerable amount of research, one gets the sense that there isn’t a medium Alÿs has not made use of. The composition, production, and documentation of the artist’s actions — both in their banality and the potent, self-reflexive effect that watching them can produce — was a prominent feature of this retrospective, not to mention of his work at large.

The artist’s recurring concerns, however, cannot be gleaned from the experience of one or two pieces, but rather, subtly emerge as one wanders from room to room, only to leave the viewer, hours later, with a lingering sense of his preoccupations — most of which are massively satirical in nature. This is the sort of feeling that often comes only after experiencing the best exhibitions; it creeps up on you.

Take, for example, the videos Re-enactments (2000), When Faith Moves Mountains (2002), Caracoles (1999), Sandcastles (2010), Rehearsal I (1999-2001), and Rehearsal Maquette (1997). Aside from the word rehearsal, what these works have in common is Alÿs’s keen interest in repetition, process, documentation, and, finally, dissolution. In some of these pieces, a sense of the ephemeral and the absurd is present throughout: a boy repeatedly kicks an empty plastic bottle up a hill in a city suburb only to watch it roll down again; like Sisyphus, a group of boys build sand castles close to the shore, only to see them devoured by the waves. Rehearsal I and Rehearsal Maquette document almost impossible actions: a red Volkswagen Beetle drives up a dusty hill in what appears to be the slums of Tijuana, Mexico, and rolls back down, drives up and rolls back down, repeatedly for twenty-nine minutes. In the Maquette version, Alÿs re-enacts or restages this already enacted scene, this time with a tiny, toy car.

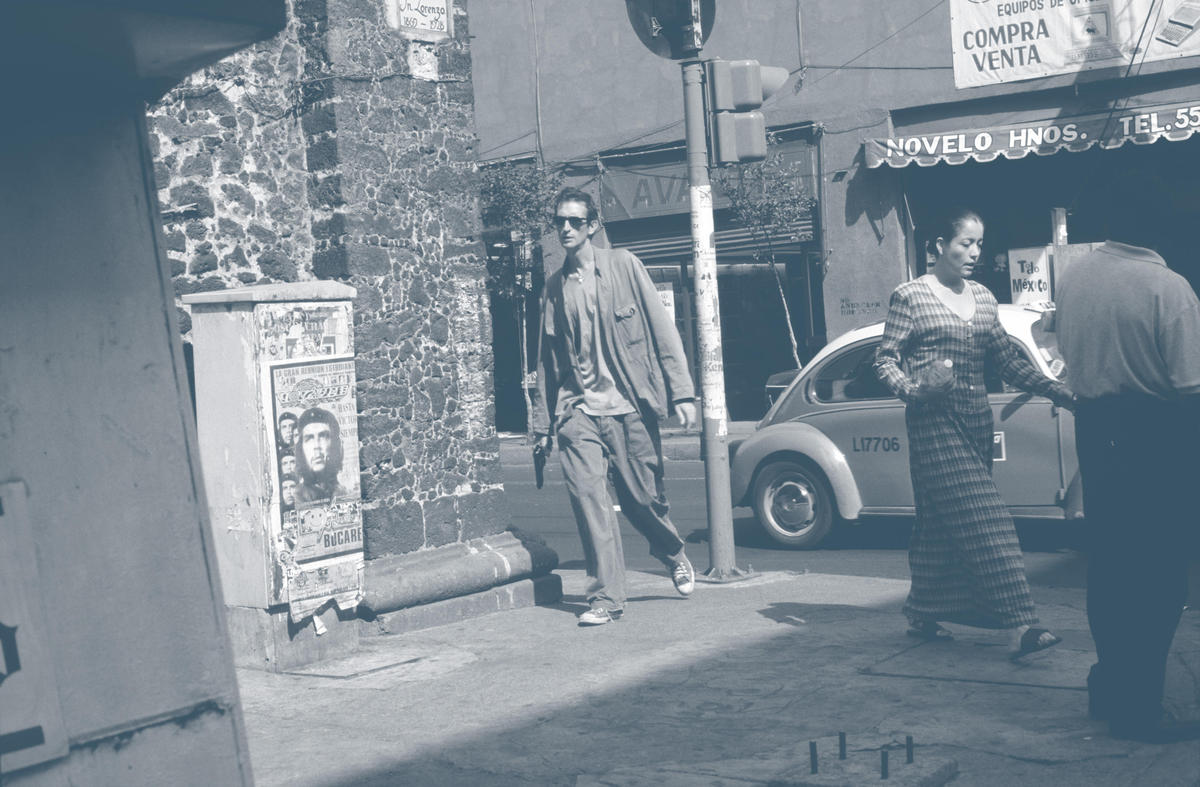

Poetic gestures and playful humor are also present in the film Re-enactments (2000), in which Alÿs rents a loaded 9mm Beretta and walks the streets of Mexico in broad daylight as Rafael Ortega follows closely behind, filming. Watching these videos a few times, one cannot help but feel the cycle of despair, poverty, boredom, and even danger that has ravaged much of Latin America and Mexico. And yet, Alÿs manages this without resorting to gratuitous sentimentality. In When Faith Moves Mountains, Alÿs orchestrates a band of school youths in Lima, directing them to shovel sand up a dusty mountain while he films from an overhead helicopter. Aside from the fact that the teenagers — many of whom, as it happens, hail from a down and out area of Lima — are literally moving a mountain, there is, too, the reality of actually succeeding in reaching the top of the mountain without rolling back down this time (unlike the works mentioned above), along with the simple, sweaty pleasures borne of manual labor. In this way, Alÿs generates a communal memory that is both heroic in tenor (moving mountains) and absurd (it moves only four inches from its original location).

In Politics of Rehearsal (with Rafael Ortega, Cuauhtemoc Medina, and Performa, 2004–2005), prevailing Western-generated discourses of development and modernity, particularly when it comes to Latin America and Mexico, preoccupy Alÿs most. Still, the artist avoids appearing preachy or uncritically militant, not only through wit, but also through occasionally unexpected juxtapositions. The film features a female soprano practicing her part as the artist stages and films a striptease rehearsal in the very same bar. These shots are interspersed with archival footage of former US President Harry Truman delivering his 1949 inaugural address, while Alÿs’s friend and collaborator Cuauhtemoc Medina lends a voice-over that addresses the spectator with astute and poignant political analysis regarding the legacy of the Cold War and its ready-made ideas about “progress” and “underdevelopment.”

As it happens, the striptease serves as an apt metaphor for Latin America’s complicated relationship to a modernity that is sought after, yet whose consequences are in many ways deeply unjust. The film hints at a modernity that is seductive, even arousing, as a striptease would be, yet fundamentally engineered. In the end, Politics of Rehearsal mirrors a rehearsal for an event — a dream — that seems hopelessly futile and may never materialize.

The video The Green Line: Jerusalem (2004) aptly bears the subtitle, “Sometimes doing something poetic can become political and doing something political can become poetic.” Though grounded in a distinct political reality — that of Palestine — it seems a testament to the fact that poetic, allegorical gestures are often the most urgent and, finally, powerful. Alÿs — acting as himself — carries a dripping can of green paint as he walks for hours across the Palestinian land and cityscape, tracing the mythic 1967 Jerusalem border — sketched arbitrarily but strategically by Moshe Dayan in 1948. Conceived as an interactive video, visitors click on a screen to choose a distinct voice-over commentary while the recreation of the border being drawn takes place — as if to demonstrate two things: the construction of Israeli national identity by demarcating what this category actually excludes, and the annexation of peoples, nations, and capitals based on arbitrary military lines.

Through the simple act of walking a line, whether accompanied by voiceovers by Amira Haas, Eyal Sivan, Eyal Weizman, Michel Warchawski, Jean Fisher, and others, or, in the case of Paradox of Praxis 1 (1997), while watching the artist strenuously push a massive block of ice through the urban fabric of Mexico City, we come to see that lines and walls are what consistently create and sustain the unjust divisions around us.