Tehran

Video Art Monthly

Tarahan-Azad Gallery

2005

Tehran

Shirana Shahbaz: Graceland

i

Silk Road Gallery

2005

A small group of smokers puffing away on the pavement by the door was the only outward indication that something was going on. But in the basement below, a busy crowd lined the whitewashed concrete space of Tarahan-Azad Gallery’s monthly video art installment.

Two projectors screened back-to-back videos, their sound spilling over into each other. Sousan Bayani’s camera floated over faces of crying babies. Simin Keramati zoomed in on a human eye, Bam’s citadel dancing across its pupil. Rosita Sharaf Jahan’s Stairs of Escape was heavy with portent. The camera followed a chadori-clad woman up metal stairs in magnifying jump-cuts, all this accentuated by an ominous bass. It was clear the actress had donned the chador just for the day, which added a sense of theatre to a film that bombarded its audience with symbolism.

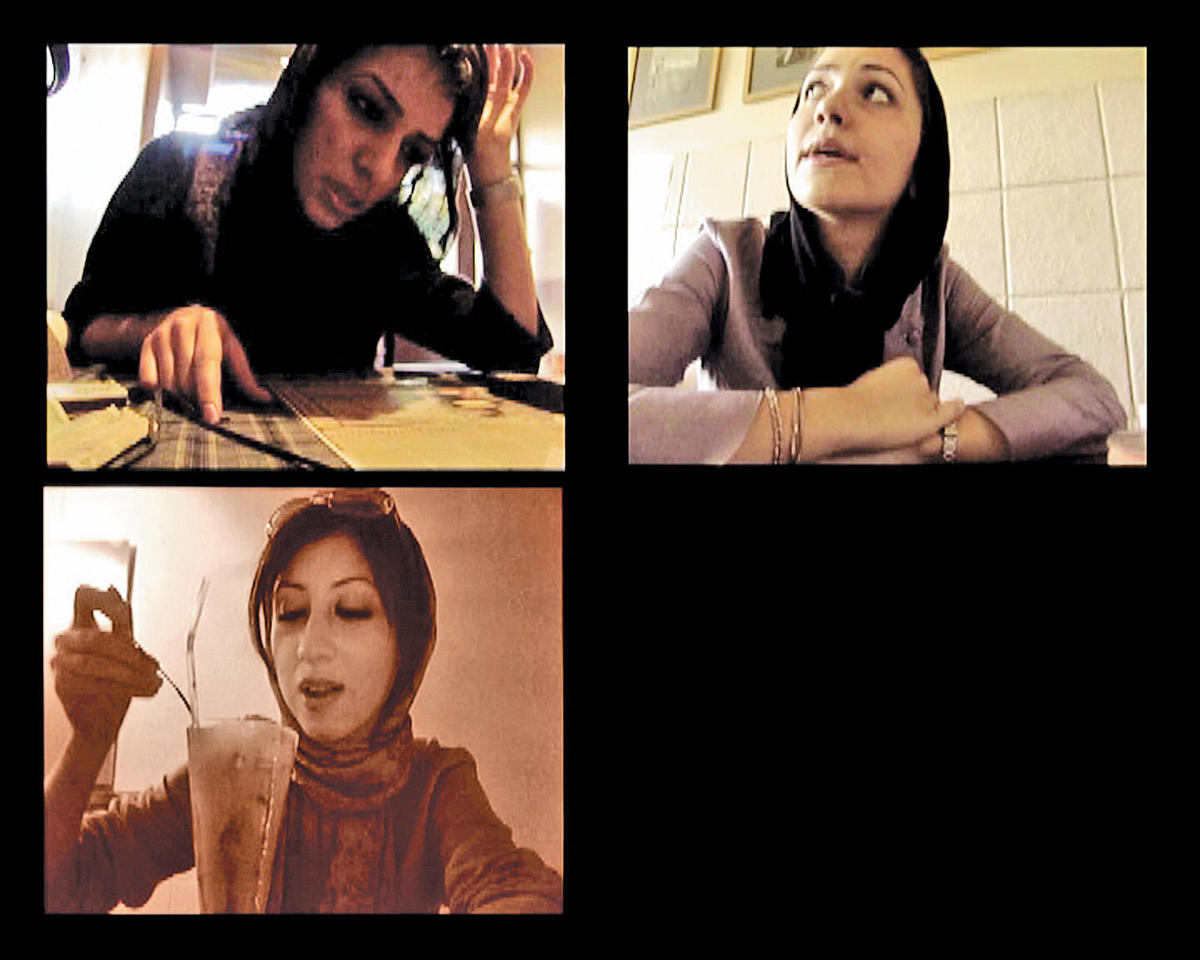

With many Tehran exhibitions embracing big themes head on — suicide, the subjection of women, death, war — Amirali Ghasemi’s Video Diary, filmed over a year, was a relief. Road-trip postcards, coffee-shop ice creams, Tehran street lights, and bare flesh draped in sarongs folded into each other on a quartered screen. Intelligently edited and underscored by a pulsating soundtrack, it didn’t batter you round the head with metaphor.

Khosro Khosravi’s The Port, shot from a single perspective, captured a day in the life of a wooden jetty on the Caspian Sea where people sat and stared out into the haze. Peacefully beautiful, if repetitive, the catalogue for the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMCA) traveling exhibition Beams of Blue; Iranian video art 2004 describes the piece as a video “painting.” This seems less odd when you consider Khosravi is indeed a painter. In fact over half the artists at the Tarahan-Azad Gallery exhibition are painters, who move into video periodically, often for commissions. This may account for the overwhelming two-dimensionality of pieces that casually appropriate the label “video art,” or “video installation,” while ignoring the potential of video technology, or even controlling the context in which it is shown. Forced to slink across the projector’s beam to reach the cakes by the kitchen, it was ironic that our shadows accounted for the only interaction between the “video installation” and the exhibition space.

Aside from painters, many other Iranian video artists are filmmakers experimenting with a fashionable new form. Old narrative habits appear to die hard, however, and this muddy middle ground makes for difficult watching. Video has only been around for five or six years in Iran but with the notable exceptions of artists such as Mania Akbari, or Neda Razavipur, few seem to be thinking outside the box. Perhaps to blame is the complete absence of teaching or even visiting video artists. Shirin Neshat’s latest work Mahdokht, screened at the TMCA’s Persian Garden, became a site of pilgrimage for young Iranian artists, so rare is the phenomenon of seasoned video artists showing their work here. Video art is a fairly recent western import, and if it is to find a new expression in Iran, it needs to be approached as a medium in itself and not simply a sexy extension of the paint brush or the short film.

While Tarahan-Azad Gallery’s videos merged into a blur, in another small but better appointed white space across town in exclusive Farmanieh, the Silk Road Gallery was hosting photographer Shirana Shahbazi’s first solo exhibition in Tehran.

Shahbazi’s exhibition arrived as a breath of fresh air in an art scene groaning with heavy symbolism. Eagerly promoted by the Swiss Embassy, who sponsored the exhibition, most of the gallery’s clientele left the jam-packed opening empty handed (not least because this Citibank Prize winner’s price tag made no allowances for Tehran).

Shahbazi’s exhibition pooled work from previous series and included landscapes, lily pads, Shanghai at night, and snow-covered American clapboard houses. But her new grouping broke up previous associations. On one wall a still life of lipstick-red apples hung above a snowy landscape beside a green American football field, while twilight faded around a pine tree on its right flank. In the ensuing roundtable discussion at the House of Artists, Shahbazi was asked to explain the relationship between the images. We settled back waiting for the usual stream of guffle peppered with references to western philosophers. Instead she said, “It’s up to you what you take from it. You see what you see.” Some wrote off her photos as weak, simple compositions — photos that anyone could have taken. But refreshingly, Shahbazi’s everyday photos refused to conform to the endless quest of photographers for something visually important, or spectacular.

Mixing photo portraits with a photograph of a nineteenth-century portrait in oils, high-rises, and plastic high-rise models, her work questioned the ethics of representation — if that’s not too weighty a phrase for a photographer who invites her audience not to intellectualize. Though an anathema to those hooked on cosmetic complexity, her work suggested a return to the undervalued act of simply looking.