Gwangju

Gwangju Biennale 2012: Roundtable

Various venues

September 7–November 11, 2012

For a curatorial studies graduate like me, the ninth Gwangju Biennale occasionally felt like “Practicum One,” in which a group is asked to curate an exhibition collectively. At Bard, where I did my degree, this course is offered in the first semester and involves asking a group of jet-lagged strangers to crank out a cohesive show together in a couple of months. A slow-mo reality show for the faculty, it often makes for a traumatic welcome to graduate school. After a few insomniac weeks of tear-jerking discussions and heartbreaks, the group realizes that it is impossible to settle on a theme, so they split up the exhibition amongst themselves and settle on a comfortably broad title. The latest Gwangju Biennale, the product of six curators, is like Practicum One with lavish budgets, abundant real estate and facilities, and — of course — the glamour of a biennial.

Under the comfortable umbrella-like rubric of roundtable, artistic directors Nancy Adajania, Wassan Al-Khudhairi, Mami Kataoka, Sunjung Kim, Carol Yinghua Lu, and Alia Swastika put forward six distinctive and occasionally wordy sub-themes ranging from Belonging and Anonymity to Impact of Mobility on Space and Time. As the curators note in their respective catalog contributions, after a year of meetings across the planet, Skype conferences, and lengthy email exchanges, they found refuge in adopting the format of the roundtable, that most democratic of bureaucratic furnitures.

Though thematically diverse, there were some common threads across the six interconnected exhibitions, not least the significant number of pieces that required audience participation — or at least, hoped to elicit a response from the people of Gwangju. Paradigmatic examples of such participatory claptrap include Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Untitled 2012, a set of ping-pong tables made out of mirror-finished stainless steel, an homage to the late Július Koller’s J.K. Ping-Pong Club (1970) which turned the Yugoslavian artist’s invisible “anti-performances” into an outright spectacle; Slavs and Tatars’ Molla Nasreddin (the antimodernist), 2012, a figure of the wise Persian fool on his donkey in the shape of a playground ride for “kids and adults alike”; and Do Ho Suh’s Rubbing Project, in which the artist traced the passage of time through graffiti and scribbles on the interiors of abandoned buildings in Gwangju by transferring them with color pencil on paper. A comprehensive list of such thematic work would be much longer.

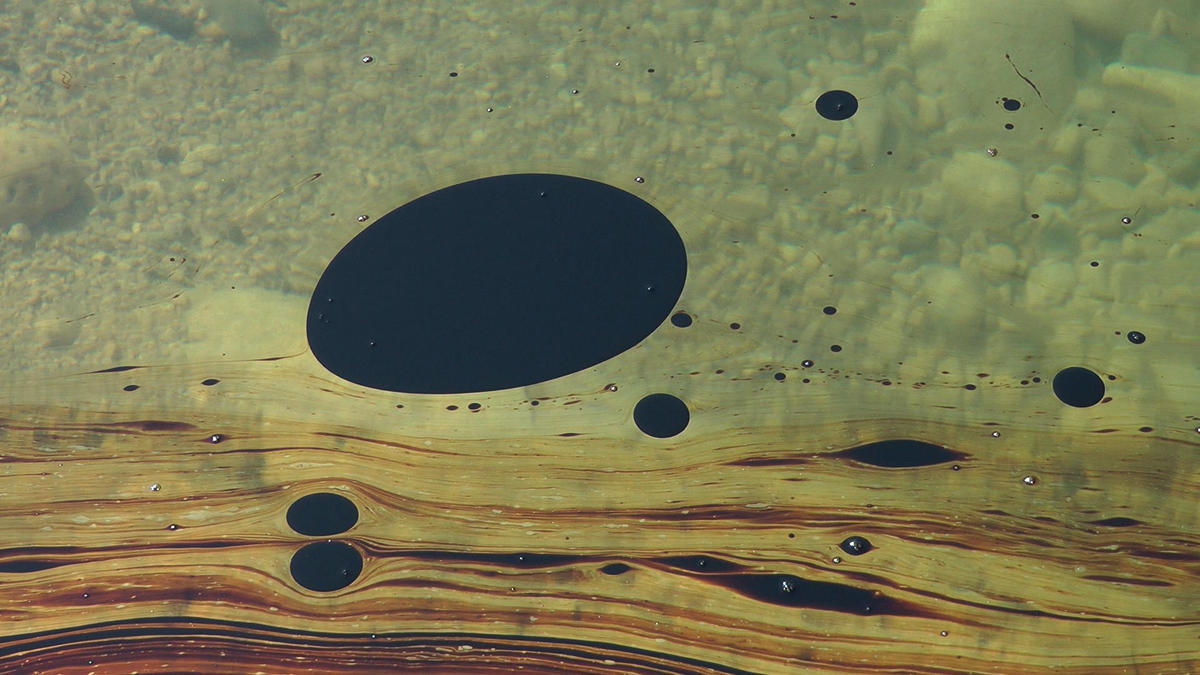

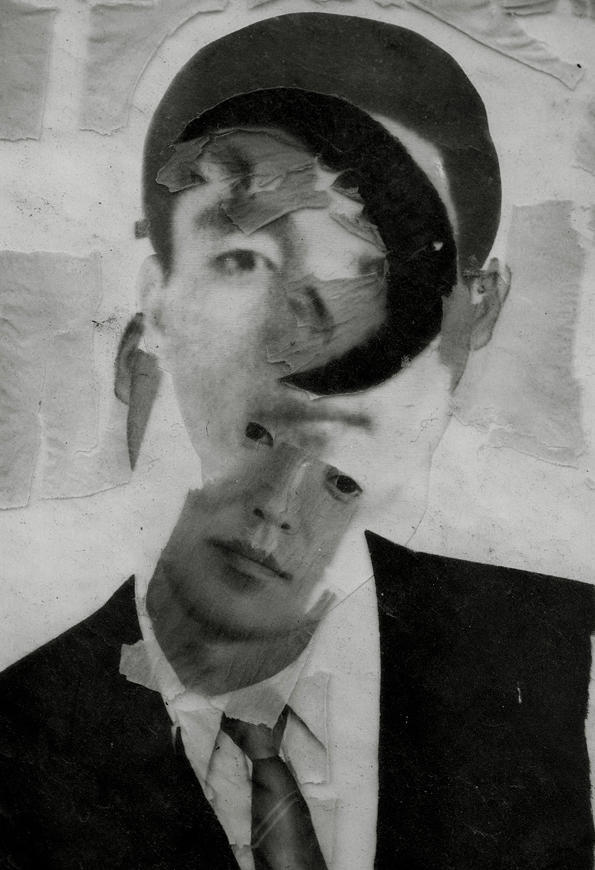

Taking cues from Re-Visiting History, a subtheme proposed by Wassan Al-Khudhairi, a number of works revisited, re-imagined, or reenacted historical events. A curious example of an artist finding himself suddenly in the midst of a defining historical moment was Fouad Elkoury’s Atlantis (1982), a slide projection of photographs of Yasser Arafat taken by the artist aboard the Greek cruise ship that carried Arafat and eighty-seven PLO leaders out of Beirut in 1982. Wael Shawky’s Telematch Sadat features a reenactment of the assassination and funeral of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat by a group of Bedouin children. In a conversation with curator Nav Haq as part of a discussion series in the biennial hall, Shawky explained how the five-piece Telematch series explored the creation of a “fake or staged event to entertain a third party, which is the art audience.” In Telematch Suburb, the artist organized a concert for a Cairo-based heavy metal band in an Alexandria village where both the band and the villagers knew he was filming without knowing why exactly. Similarly, in Telematch Sadat, the assembled children had no memory of the assassination and only followed orders. “The event itself became the priority,” Shawky claimed. Babak Afrassiabi and Nasrin Tabatabai’s two-channel video installation Seep revisited an unfinished industrial documentary produced by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company while attempting to situate the footage within the context of contemporary Iran. And one of the most memorable pieces in the show may have been Faycal Baghriche’s The Message Project, in which the artist revisited Moustapha Akkad’s film The Message (1977), about the birth of Islam. Catering to both Arab and Western audiences, Akkad shot English and Arabic versions of the film on the same set, producing and releasing two versions of the same film for each market. Baghriche weaved together the two original versions of the movie into a single feature. In The Message Project, characters in the story effortlessly shift from one cast to the other (for example, the prophet’s uncle Hamza shifts between the actor Abdullah Gaith and the Mexican-American actor Anthony Quinn). Functioning in a space beyond language or ethnicity, the piece provides a subtle commentary on the production of universal human gestures via cinema.

Other notable pieces included xurban_collective’s Evacuation #2: Under One Minute, which took on the congregation of immigrant communities around martial-arts parlors in the US, Europe, and Korea and investigated the spatial dimensions of these parlors and the communities to which they give shape. Kim Boem’s Yellow Scream (2012), a single-channel video piece installed in Daein market — the city’s last remaining traditional bazaar — was a simple yet hilarious tongue in cheek commentary on artistic expression, while in 12 Sculptural Recipes the artist prepared paper-clay chickens inspired by prevailing artistic modes, e.g., cubism, realism, etc. The biennial also published Born Again, a collection of ironically dry and laconic poems by Chinese poet Han Dong that especially sat well with this recent émigré to Los Angeles with lines such as “I cut through this city blanketed with thick fog/cannily avoiding the traffic.”

Curatorially, the decision to move beyond the exhibition hall played out well in Gwangju, deftly untangling the density of the gallery spaces. In its various forms, the biennial extended into the old Daein market, the Mugaksa Buddhist temple (whose head was an artist in Paris for a brief period before becoming a monk), and Cinema Gwangju. It also included a series of online publications produced during the show’s span and available for download on the biennial’s website. Al-Khudhairi’s curatorial input was especially helpful as her contributions to the exhibition were distributed around the galleries, providing for a less jarring curatorial flow. The artistic directors refrained from direct curatorial interventions except for Nancy Adajania, who created a mandala-shaped gallery to hold a collection of different photographic series by Noh Suntag (including The Forgetting Machines series (2006–2007), in commemoration of those who died during the Gwangju Democratization Movement in South Korea) and a reading station in the middle of the exhibition hall with pamphlets and texts about the Non-Aligned Movement — possibly a fantastic PhD research project but rather misplaced in a contemporary art exhibit. Adajania’s dithyrambic press presentation, commenting on art’s role in revolutionary politics, made some members of the audience want to throw away their canvas bags and bring down the first government they would encounter outside the exhibition hall.

Still, in spite of the spirited extension outside the exhibition hall, and a lot of good work on show, the ninth Gwangju Biennial never shed the image of a polycephalic monster, its heads pulling in six disparate directions. Each of the curators had the experience and expertise to direct an entire edition of the exhibition; it was therefore unsurprising that the torch relay from Massimiliano Gioni (who received the key to the city of Gwangju at the event’s opening ceremony) to six pan-Asian women provided for ample gossip at the hotel bar as to the skewed gender politics of the art world.

By foregrounding the individual vis-à-vis the collective, Carol Yinghua Lu’s idiosyncratic subtheme Back to Individual Experience may have provided the most fitting introduction to the show’s multiplicity of curatorial positions. In her catalog contribution, the Beijing-based curator offered that the return to individual experience is meant to “reiterate the independence of individual spirit, the equality of all positions, both in the makeup of the art system and the makeup of our social structure and our perception of the world.” As such, the show provided for a critique of the crisis of thematic exhibition making in curatorial practice by highlighting the personal encounter with the work of art. At the same time, the biennial’s concoction of approaches reflected a curatorial homage to the discipline’s founding father, Harald Szeemann, and his maxim of “individual mythologies.” And yet, while in the face of the current version of Chinese communism this position might seem to represent a practice marked by emancipatory politics, Back to Individual Experience might also swiftly be translated into the cultural policy of liberal capitalism (or rendered a Tea Party bumper sticker).

Balancing myself on the steep grass slope above the occupied bleachers of the open-air auditorium during the opening ceremony, I watched various local authorities and politicians deliver sporadically translated speeches on the importance of the exhibition for the city and for South Korea’s nation-building project. At times, they sounded maybe a bit provincial; at others it tasted like classic nationalist propaganda. But all that was forgotten minutes into the after-party, where the uniquely global beats of Psy’s “Gangnam Style” brought together every side of the proverbial roundtable. Pop and politics aside, in the context of Gwangju, the biennial fulfilled its promise of making the city a cultural hub, even if a transient one. Some might argue that this stance is bankrupt, politically and economically corrupt — a tool for gentrification. But if the alternatives are situated somewhere between an art fair and a Gehry building, I will opt for the biennial over and over again.