To keep my mind off the waiting, waiting, I play bridge.

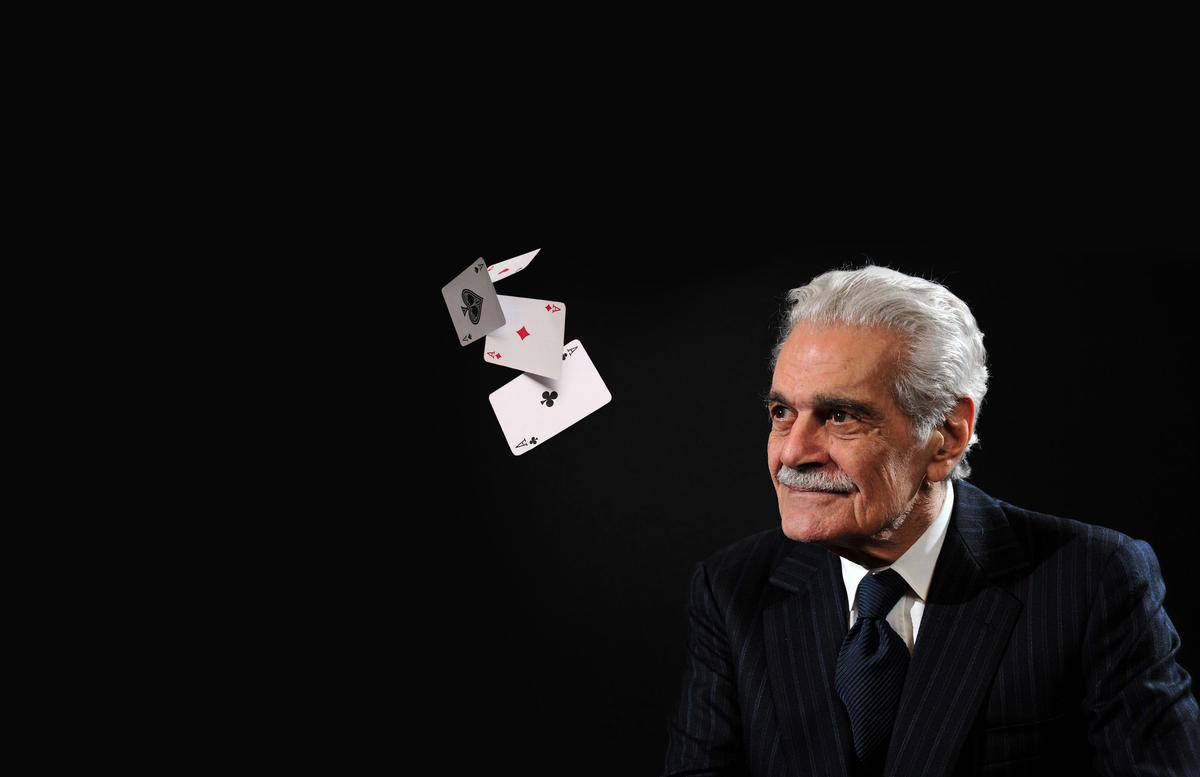

Omar Sharif represented Egypt in the 1964 Olympics for the game of contract bridge, according to one of the more benign rumors circulating about him on the internet. The secular trinity of Google, Google Books, and Wikipedia are uncharacteristically useless in confirming or denying the story, but the fact is, it just can’t be true, because bridge isn’t an Olympic sport. Bridge players have tried for decades to make it one, and in the late 1990s, the Olympic Committee recognized as it as one of two “mind sports,” along with chess. But the committee, which apparently finds curling perfectly tolerable viewing, has yet to be persuaded that the bridge is, in any conceivable sense, watchable. After considerable digging, I was able to trace the source of the rumor to a 1966 story in the Washington Post, which reported that Omar Sharif had captained the United Arab Republic’s bridge team for the World Bridge Olympiad of 1964. So much for the legacy media: there was indeed something called the World Bridge Olympiad, held every four years between 1960 and 2004, but the United Arab Republic — the short-lived union of Egypt and Syria — ceased to exist in 1961.

Still, there is something apt about the bogus story. If anyone could have turned contract bridge into a spectator sport, it would have been the Omar Sharif of the swinging sixties. He was religiously devoted to the sport, occasionally refusing films if they interfered with his bridge-playing schedule. And he tried valiantly to bring attention to the game, even forming a barnstorming “Omar Sharif Bridge Circus,” a caravan of crack players who traveled the world playing tournaments and exhibition matches. Truly, there has never been a more beautiful, more glamorous bridge ambassador than Omar Sharif. The only way he might have given the Olympic Committee something to watch is if he had agreed to compete, like Olympians in the age of Pindar, naked.

I have no plans for tomorrow and I don’t have memories of yesterday. I live now.

The acting career of Omar Sharif, né Michael Demitri Chalhoub, is generally thought to have begun in 1953, with Youssef Chahine’s Sira`Fi al-Wadi (The Blazing Sun) in which Sharif starred opposite his future wife Faten Hamama. The truth is, it began several years earlier, when he was still a teenager enrolled at Cairo’s posh Anglophone Victoria College. He appeared as Mrs. Hardcastle in She Stoops to Conquer, a venerable eighteenth century comedy of manners, and delivered the play’s opening lines:

I vow, Mr. Hardcastle, you’re very particular. Is there a creature in the whole country, but ourselves, that does not take a trip to town now and then, to rub off the rust a little?

Gilbert de Botton, the future financial wizard and Montaigne scholar, played Mrs. Hardcastle’s stepdaughter Kate. This was a British boarding school, after all, and boys will be girls.

Sharif ’s 1977 memoir, The Eternal Male, contains no recollections of cross-dressing, in that production or any other. Its author does, however, recall “thrilling my classmates with lines I’d learned by heart with all the confidence and conviction of a born ham.” Among the thrilled was a smaller, shier “VC-Cairo” boy three years his junior, whose end-of-century memoir, Out of Place, we have to thank for the insight that that icon of virility who emerged from a desert mirage to enter collective fantasy had prepared for that and other priapic roles by playing an eccentric, ambitious, over-protective mother. The younger boy, Edward, had been bullied by Michael, and took as much pleasure in witnessing that performance as his older self did in recalling it.

Michael may have drawn on personal experience for the role of Mrs. Hardcastle. His own ambitious mother, a “kind of crazy woman,” he told Al-Jazeera in 2007, “who had decided when I was born that I was going to be the most handsome and most famous man in the world,” found to her horror that by age eleven he’d grown fat. “My son is ugly, I can’t stand it!” she said, and promptly switched him out of his French boarding school into an English one, reasoning that the worst food in the world was English. Within a year he was lean and handsome again. Had it not been for VC-Cairo, “I would have been a fat Levantine timber merchant like my father!” Instead he was an athlete, a budding actor, head prefect of a colonial boarding school, and Edward Said’s “chief tormentor.” It was the first of many transformations.

It is a taste I have for working out puzzles — cards, bridge, maths, it’s the same thing. Bridge like math is all about logic, but with bridge every two or three minutes, every time you deal the cards, you have a new puzzle.

His next big role was one he cast himself in. Born Catholic (later rumored to be Jewish), he converted to Islam, maintained his agnosticism, and rechristened himself Omar Sharif. He converted to marry a Muslim girl; the rechristening, too, mixed aspiration and practicality. “I thought to have a name that the Occidentals would have no trouble remembering,” he said:

The name Michael annoyed me. I tried to come up with something that sounded Middle Eastern and could still be spelled in every language. OMAR! Two syllables that had a good ring and reminded Americans of General Omar Bradley.

Next, I thought of combining Omar with the Arabic sherif [of noble ancestry] but I realized that this would evoke the word “sheriff,” which was a bit too cowboyish. So I opted for a variant.

Sharif had graduated from VC-Cairo and quickly became an Egyptian matinee idol; Said was kicked out for being a “troublemaker,” then sent by his parents to a Massachusetts boarding school, where he was “found to be morally wanting, as if there was something mysteriously not-quite-right about me.” In a few years’ time Sharif and Said found themselves at the heart of things in the antipodean capitals of the Jewish-American twentieth century, Hollywood and Manhattan, where they would reprise their practiced roles.

Said, whether with Arabs or Americans, would “always feel incomplete. Part of me can’t be expressed.” Sharif, by contrast, when “confronted with a civilization that differed greatly from mine… was very much at home. Human contact has always been easy for me.” Said lived almost half a century in the same city, at the same university, yet still felt an exile, always “reliving the narrative quandaries of my early years, my sense of doubt and of being out of place, of always feeling myself standing in the wrong corner, in a place that seemed to be slipping away from me just as I tried to define or describe it,” while Sharif was an exile in the Nabokovian mold, living in an archipelago of borrowed rooms and impersonal hotels, a vagabond aristocrat, always at home.

I live in the hotel Royal Monceau of Paris because the proprietor is a Syrian friend of mine who invited me and is enchanted that I am his guest… I believe he always gives me the same room and I do not know if it overlooks the patio or the street. I have never opened the curtains to see what there is outside. I have already seen all possible landscapes… In the room I do not have anything personal, only my Armani suits. I wear a few each year and then donate them to Father Pierre… In my room there is neither a book nor a photo. In Deauville, the same. And in Cairo I have a small apartment with some memories, the minimum. If they give an award to me, I accept it, I am grateful for it and I leave it in the hotel. I do not have a car, I do not have possessions.

Sharif and Said indeed might have been comic transnationalist doppelgängers in a Nabokov novel, or for that matter tragic ones in a Sebald novel. Actually, I think they are tragicomic transnationalist doppelgängers, of a sort, in a novel by Ahdaf Souief. Her 1999 Map of Love features two protagonists, both of whom are clearly modeled on different aspects of her great friend Said: one is Omar, a Jerusalem-born pianist and political activist based in New York City, who identifies as Palestinian, Egyptian, and American; the other is Sharif, Omar’s legendary great uncle, a charismatic intellectual who writes about the encounter between the Arab world and the West.

Sharif found a better plan, aware from the bidding that he was facing bad breaks. He won the first trick in the dummy and ran the club jack, losing to the king. He expected that if he lost to a singleton, West would have to do something helpful, and so it proved.

The sense of exile crystallized for both Sharif and Said in the summer of 1967. In Said’s case the catalyst was the lightning-fast Israeli defeat of the Arab armies. The annexation of Jerusalem, where he was born, and the occupation of what remained of Palestine, left him “for the first time… genuinely divided between the newly assertive pressures of my background and language and the complicated demands of a situation in the US that scanted, in fact despised, what I had to say about the quest for Palestinian justice.” Things were even more complicated for Sharif. As the Egyptian Air Force was being decimated on the tarmac, principle shooting had just begun for Funny Girl, which had Sharif playing Jewish con artist Nicky Arnstein and kissing Barbara Streisand, at that point an increasingly vocal Zionist. “Omar Kisses Barbra, Egypt Angry,” read the headlines. “Egypt angry!?” Streisand is reported to have sneered. “You should hear what my Aunt Sarah said!” Aunt Sarah’s outrage was in turn no match for that of General Nasser, who made clear that Sharif was no longer welcome in Egypt. He was not to visit until a decade later, after President Ford introduced him to Anwar Sadat, and Sadat convinced him to return.

I’m the only actor I know who is a nomad. I never belonged where I was working. I’ve worked in dozens of countries and then gone home to hotels.

Sharif ’s routine, in the hotels he has called home, in Paris, Cairo, and elsewhere, consists of rousing himself around noon, stretching out in a hot bath for hours, reading newspapers in several languages — “I speak many languages, but I don’t have a mother tongue. I don’t speak any language without an accent, even Arabic” — before heading down to the hotel bar for a cocktail, and to watch the horse races on television.

In his gambling days, he’d then take a trip to town, rub off the rust a little. He has lost enormous sums at various times. At such moments, he says he “felt nothing” — no repentance, no remorse or self-disgust. When he gambled away his Paris apartment one night, he got up in the morning, phoned his agent, and said, “Find me any trash. I need money.”

Sharif kept his bridge sessions separate from his high-stakes gambling. Bridge had a formal purity, uncontaminated by thought of gain, or motives about the future; its strategies were for their own sake. If a passion had to be sullied, let it be the cinema.

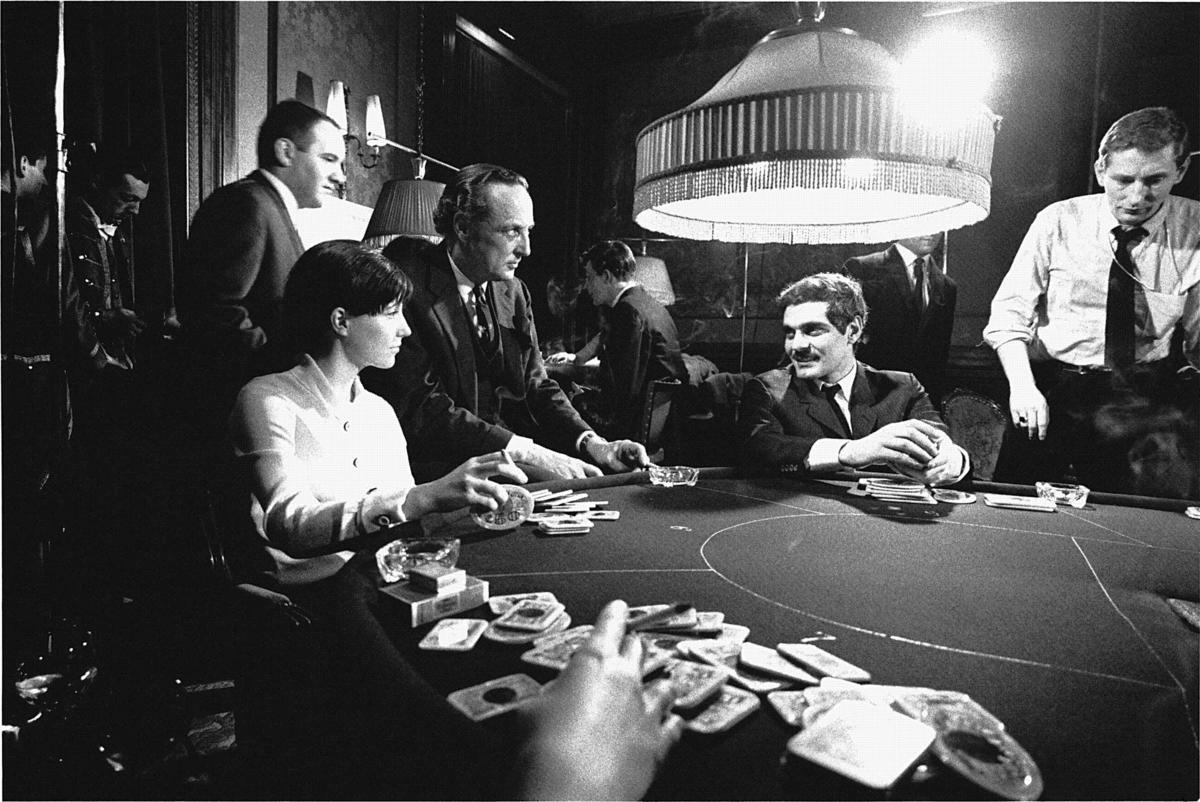

When you make movies, you wait two or three hours to do two or three minutes’ work… Boredom is always reflected in the face and picked up by the camera. I started to play in order not to be bored. I could have easily picked up a book on fishing. But bridge fascinated me. My interest in bridge is another form of destiny.

Sharif was first exposed to cards and gambling as a child, when his mother played with King Farouk, but he didn’t learn bridge until, at the age of twenty-two, he found himself stranded on a film set with a lot of down time and idled it away reading a book on bridge someone had left lying around.

Bridge is generally understood to be the most strategy-based of all card games. (For a dissenting view, see “Cerebral Eruption” by Christian Rudder on page 100.) A “mind sport” like chess, bridge is fundamentally different in that its design does not seek to eliminate the role of chance, but rather to proliferate the points of contact between strategy and contingency. Chess begins always with the same arrangement, and maintains transparency throughout: the only unknowable is the mind of the other player. Bridge by contrast begins in randomness, with each player knowing only his own cards, which he tries to signal to his partner and obscure from his opponents, until formal distribution clarifies, strategic possibilities narrow, and a narrative telos emerges.

In bridge, two teams of two players are arranged like points of the compass: North and South are paired, as are East and West. After the deal, the “auction” begins, with players taking turns “bidding,” that is, wagering how many tricks their team can win once play begins. The highest bid becomes the “contract,” and play begins, after which the “declaring” side is rewarded for fulfilling their contract, or penalized for falling short. There is a great deal of tacit, oblique communication between partners throughout, the success and subtlety of which depends not only on individual skill but on the strength of the partnership, the synchronization of instincts, intuitions, and styles of play.

Bridge has, moreover, an unusually elaborate, evocative, and hermetic vocabulary, much of it derived from the eighteenth-century heyday of bridge’s direct ancestor, whist: slam, ruff, slough, rubber, dummy, vulnerability, flag-flying, psychic bid, semi-psychic bid, cue bid, courtesy bid. Forte, fortissimo, pianissimo and other musical terms are sometimes used to describe the tenor of auction bidding. A player “finesses” by playing a series of low cards in a suit in order to draw out and drain his opponent’s high cards. A “huddle,” according to a 1930s writer who knew his Shakespeare, refers to “a session of sweet silent thought indulged in by a player either during the bidding or during the play.” As in: “East, a player of considerable experience, emerged from his prolonged huddle with the nine; thereupon, declarer rattled off nine tricks without giving a thought to the spade finesse.” That’s from “Defender Finds Self in Doghouse,” one of the four thousand, seven hundred, and eleven bridge columns Sharif wrote for the Tribune in the 1970s and ‘80s. Nowhere in those hundreds of thousands of words does he trade in celebrity schmaltz or anecdote. Nowhere does he do anything except talk about bridge strategies and scenarios, in the most rigorous possible way.

My life, until I found myself in that remote corner of Jordan, had been only a succession of landscapes, places where people and animals lived together. And there I was under that canopy riddled by little fireflies, subjected to the uniform desert, obeying its law, its magic. There were a thousand of us and yet I was alone, face to face with myself. My mind had been trained by my French studies in what is called Cartesianism, but in the desert my Islamic atavism surfaced.

Sharif, who named himself after an American military general and has described modulating and thickening his accent for the purposes of seduction, has always had a gift for seeing himself through Western eyes. His penetrating gaze, as the anthropologist Steven Caton has pointed out, is also an Orientalizing one, and never more so than when trained on his own reflection: he refers to his “Middle Eastern fatalism” and “laziness,” his “very Eastern, very melodramatic” emotions, to “the Arab’s character” being “forged among the dunes where he pitched his tent.”

“Islam!” he exclaims in The Eternal Male. “This Arabic word means ‘resignation’ and codifies, all by itself, the law of the desert.”

If Sharif ’s “Islamic atavism” surfaced in the sands of the Jordanian desert, Lawrence of Arabia’s director was there to reassert Cartesian rigor. “Arab film actors use lots of mime and grandiose gestures… David Lean curbed my Middle Eastern temperament mercilessly. ‘He who can do the most can do the least’, he told me,” and Sharif learned thereby to play his cards close to his chest, to be cryptic instead of operatic. Skills like that could be put to all manner of use: to radiate enigmatic absorption onscreen — is it contemplation, admiration, or desire playing across Ali’s face as he watches Lawrence ride off toward the horizon? — say, or to false-card a king such that West knows what you’re up to, but not North and South.

East would have put up the ace of hearts if Sharif had led a low heart from dummy, but the jack of hearts was a different story. East thought declarer was void of hearts, so he played low. Sharif won with the queen of hearts and looked at me sympathetically. He was about to win the rubber with a second slam.

With the help of Martin Sokolinsky, The Eternal Male’s Brooklyn-born translator, Sharif was recast yet again, this time not as the polished cosmopolitan, mandarin in manners and elusive in his ethnicity, but something altogether different and surprising: an American, born and bred. The narrative begins with Sharif — on the eve of Lawrence of Arabia’s American premiere — sharing a jail cell with Lenny Bruce and Peter O’Toole, and speaking an unmistakably American vernacular:

Obviously, I’d never have believed it. Get to Hollywood and spend your first night in jail — that isn’t exactly obvious. Especially when you haven’t done anything wrong. When you haven’t killed your father, pimped for your sister, or trafficked in narcotics…

This Sharif fits right into an American genealogy of bad-boy innocence and longing, which — along with what Mark Twain called his hero’s “sound heart and deformed conscience” — runs from Huck Finn to Fitzgerald and Hemingway’s heroes to Holden Caulfield (and beyond Sharif ’s time to a different Omar, the sound heart and deformed conscience of David Simon’s The Wire). A persona, in short, the polar opposite of European and Oriental old-world decadence, whether European or Oriental.

The Winnipeg bridge promoters met all of us at the airport and presented Omar with a beautiful (not to mention warm!) authentic buffalo coat to ward off the too-cold evil spirits. Omar was delighted by both the warmth of the coat and the warmth of the presentation. He proudly sported the coat all week — at least until we left the following Monday, when this same entourage relieved Omar of the coat, belatedly explaining that it was just a loan… Our final stop was Philadelphia. It was particularly noteworthy because of the history of Philadelphia bridge, the cradle of so many of our top bridge personalities. The city has produced such impressive superstars as B.J. Becker, Johnny Crawford, Bobby Goldman, Charlie Goren, Bobby Jordan, Norman Kay, Peter Bender, Arthur Robinson, Sidney Solidor, Helen Sobel, Charlie Solomon, and Sally Young…

If Ali the Arab and Dr. Zhivago brought Sharif into the bedroom of the American mind, it was the bridge player (and bridge columnist for the Chicago Tribune) who brought him into the middle-class salon, conferring on his ineradicable glamour something suburban and unthreatening. He wouldn’t sleep with your wife; the most he would do is take advantage of her being star-struck, so as to beat her all the more resoundingly. You could hand him an “authentic buffalo coat,” and he’d wear it! And then you could take it back. His languid eyes seem somehow avuncular when they gaze at us from the back of Bridge for Dummies, or from the packaging of Omar Sharif Bridge, a video game.

In bridge terms, free will appears to prevail over predestination all the time. Within the laws of the game, bidders can do whatever they like and opening leaders can choose whatever card they like. True? Not quite.

At a certain point Sharif ’s elaborate formal strategies for keeping the present uncontaminated by past and future began to falter, and he came to regret, of all things, his success. “Fate threw me into the diaspora, made me succeed in cinema and live outside my country.” If it weren’t for Lawrence of Arabia, he has said on several occasions, he might have remained in Egypt with his wife, he might have fathered ten children. He and Faten were happy for sixteen years; she returned to Egypt during the time he was effectively banished, because she missed the cinema. From then on he lived in hotels; there was never another real partnership, he says, only flings.

I dreamt about cards. I was driven by the competition. I was good at it and I wanted to be perfect. But… you can never achieve perfection. You get better, but because it is a game of partnership, there is no way you can get there. You need to perfect a system between you and your partner.

Relatively late in his life Edward Said decided that even if a Palestinian state were to come into existence, it would be “too late” for him to return there. “I’m past the point of uprooting myself again,” he said, and then added: “New York is the exilic city. You can be anything you want here, because you are always playacting; you never really belong.” He and his old tormentor would continue to mirror each other, even as their trajectories crossed paths and they reversed roles. By the late 1990s, Omar Sharif had begun to feel what Said had experienced as the defining condition of his existence from early adulthood on. “I felt I had lost my identity,” Sharif told a journalist. “I was a foreigner everywhere. When I came back to Cairo and saw childhood friends, it made me realize that I want to spend my last years here, I want an old man’s routine, to sit and chat about the past with people who remember.” He now resides in Cairo’s Semiramis Intercontinental, where, at the time of this writing, he is watching the revolution from his window and imploring Mubarak to read the writing on the wall. He has given up the game of bridge, saying that he’d grown tired of dreaming about his cards, and how he might have played them differently.

Italicized passages of this article incorporate material from The Eternal Male; published interviews with Omar Sharif; bridge columns by Alan Truscott, Charles Goren, and Sharif; and The Lone Wolff: Autobiography of a Bridge Maverick, by Bobby Wolff.