Hrair Sarkissian’s best-known work to date is a series of large color photographs depicting empty streets in early morning light. In one shot, we see three palm trees sprouting from a median dividing a wide cobblestone avenue. In another, we see a portrait of the late Syrian president Hafez al-Assad or a poster advertising the aging Lebanese pop star George Wassouf. In another, a hulking concrete overpass sinks half of the image in darkness. In another still, thick electrical cables loop over a dense tangle of buildings on a hill in the background. One’s gaze slips uneasily across these images. They are too deliberately composed to represent vernacular street photography, the landscapes too varied to capture the texture of a particular urban fabric. They are at the same time not consistent enough to fetishize the form of any specific architectural typology.

Something about these photographs remains studiously unfixed, to the extent that you eventually have to ask, what exactly am I supposed to be looking at? Then perhaps your eyes shift, you see the label on the wall, and you note the title of the series: Execution Squares, from 2009. All of Sarkissian’s images — shot in the Syrian cities of Aleppo, Damascus, and Latakia — portray public squares in which capital punishment has been carried out, usually by hanging and usually at dawn. You look again at the photographs and realize that what eludes your gaze is precisely the emptiness of those streets, which you now perceive as haunted, drained of inhabitants but filled, perhaps, with ghosts, with the unsettling knowledge of what has passed. There is, too, a premonition of what occurs as these cities sleep.

A Syrian artist of Armenian origin, Sarkissian is adept at endowing such empty spaces with meaning, and exploring the impressions that certain political realities and historical events leave on the surfaces of different cities. He avoids photographing people; instead he prefers abandoned structures (such as the Soviet-era metro stations that were cleared out by the Armenian police force for the series Underground, also from 2009), derelict building sites (including the half-finished luxury real-estate projects in Yerevan’s city center that give evidence of a boom-to-bust housing cycle in the series City Fabric, from 2010), or architectural models he assembles in his studio (such as the tiny buildings made of toy blocks, which were reconstructed from memory and represent the houses in the village from which his grandfather fled during the Armenian genocide in 1915, for the series Construction, from 2010).

“It’s always been confusing for me to include people in my images,” Sarkissian says. “I try to avoid actors and create an empty stage. My main interest is in the spaces themselves, how the viewer and I relate to these places without having any other interruptions or references to distract our perception and our attachment to these particular spaces, to the experience of being within an empty city.”

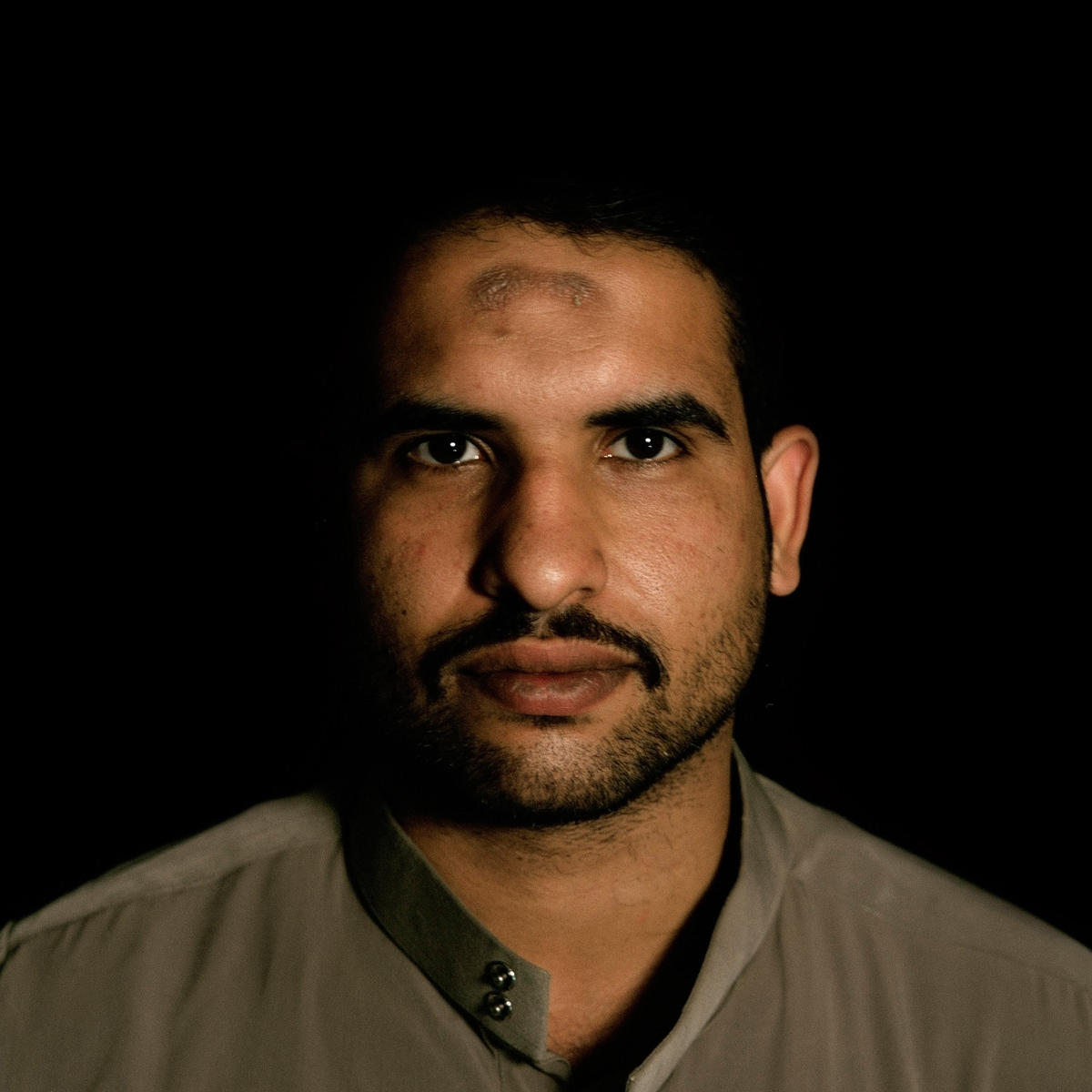

Even on the rare occasions Sarkissian has taken portraits — for example, of pious Egyptian men for the series Zebiba, from 2007 — his interest is less in the men’s faces than in the scars on their foreheads, the marks of their religiosity as traces of something else.

All of this, then, makes the twinned series Sarkissian Photo Centre and My Father & I, both from 2010, something of a surprise. Of course the former fits within the artist’s overall oeuvre in that it depicts the empty rooms of a photo lab, though the spaces are more rich, more intimate, and heavier with implied human presence than anything in his other, more desolate landscapes. But My Father & I is straightforward stylized studio portraiture — the neutral backdrops, the three-quarter profile poses, the proud, serious looks that aim just wide of the lens.

It also proceeds chronologically through time, beginning with portraits of Sarkissian’s father as a very young man, following him as he matures into adulthood, and then jumping to Sarkissian himself, whereas the artist’s other series tend to capture a singular, ethereal moment that is more or less now. And while some element of the Armenian experience — the traumatic history, the scattered community — is almost always lurking somewhere in Sarkissian’s work, the story is far more personal in Sarkissian Photo Centre and My Father & I, delving into the space where his father worked, where he grew up, and where the two of them finally fell out, leading to the end of a family business and allowing Sarkissian to become an artist.

“Before becoming a photographer, my father was working as a car mechanic in a garage in Aleppo,” he says. “Every day during lunchtime, my grandmother asked him to sit and eat in the corner of their courtyard because he was always wearing dirty clothes, and she wouldn’t let him to join the family table. He had a complex about being excluded. He decided to become a photographer because it was a clean profession.”

Sarkissian’s father moved to Damascus, where he apprenticed with an Armenian photographer named Dikran. Then he opened a studio with other photographers, who did portraiture and wedding photography alongside developing, printing, and color processing. In 1979, Sarkissian senior opened the first color lab in Syria, initially called Dream Color and later changed to Sarkissian Photo Centre.

“I loved this space,” the artist says. “As a kid, I used to sneak into my father’s closet, take out his camera, and imagine myself becoming a photographer. I always say that I was born with a camera in my mouth. I spent more time in the lab than at home. Every summer I went to work there. In the beginning, I was just making coffee, cleaning, and sitting next to my father, helping him put negatives in envelopes. I hated doing that, because I wanted to be behind the printer. I wanted to take my dad’s place.”

Eventually, he did. After graduating from high school, Sarkissian joined the lab full time and stayed for twelve years. But in the late 1990s, he started working as an occasional fixer for foreign photographers. Without his parents’ knowledge, he applied to an art school in France. He got in, and he left.

“A year later, I came back, and I told myself I could take care of my father’s shop and become an artist at the same time. It didn’t work out. I clashed with my father. He didn’t want me to be an artist. He said I couldn’t live off of art. The tension was always there. One day it exploded and I quit.”

Sarkissian’s father is now seventy-five, and the lab has closed. Before it was packed up, however, Sarkissian asked his father for one last photo session. The son documented the space and riffled through the archive to find portraits of his father. The father, in turn, did what his son has always been so reluctant to do. He took a series of portraits, and in doing so, reconciled their relationship. At the moment, Sarkissian is on a residency in Istanbul, and finding it a difficult place to be, like living in those eerie spaces of Execution Squares. The work he is producing concerns the city’s Armenian community and, to be expected, is digging up old ghosts. “It’s going slowly,” he says. “I have this weight on my shoulders whenever I am out in the streets. It’s too much. Getting to certain people, asking them certain questions… I have been thinking about being in Istanbul for the past two years, and I think I will continue thinking about this place as long as I feel this burden on me.”