On Mondays, at midnight or a little after, I arrive at the Greek Mythology in Taipa, where I play when I have nowhere else to go, when I feel the goddess of luck, Guan Yin, is with me. It’s one of the older casinos, archaic and run down, but I like its bars stocked with Great Wall and Dragon Seal wine which you can mix with Dr. Pepper. For that matter, I like the Greeks themselves, Zeus at the top of the gold staircase and the friezes of centaurs. I like the receptionists in cherry-red hats who sleep with you if you pay them enough. I even like the deserted traffic circle at the end of the street where I can go to catch my breath during a losing streak. The air in Macau is always sharp and clean, somehow — except when it’s foul and humid.

The crowd is mainlander at New Year, an outpouring of the nearby cities of Guangzhou and Shenzhen and their choking suburbs. The people look like swarms of ducks. I wonder what they make of the murals of ecstatic nymphs. Among them one can spot the safety-pin millionaires, the managers of the Pearl River factories, the mom and pop owners of manufacturing units specializing in computer keyboard buttons and toy cogs and gears for lawnmowers — all here to blow their hard-earned wads on the I Ching. The doors are that bright gold that the Chinese love, the carpets that deep red that is said to be the color of luck. Droplet chandeliers hang down from ceilings painted with scenes from Tiepolo, with zephyrs given Asian canthi. Corridor flowing into corridor, an endless system of corridors, like every Macau casino.

I pass into a vestibule where the glass screens are frosted with images of Confucius and naked girls. In a private room, briefly glimpsed, two Chinese players are laying down hundred-Hong-Kong-dollar bets with a show of macho lethargy and indifference. One of them smokes an enormous cigar, from the open box of complimentary Havanas on the table, flicking the ash into a metal conch shell intended to echo the cheap reproductions of Botticelli cut into the blue walls. My hands begin to sweat inside the gloves I always wear in gaming houses. The smell that curls into my nose is that of humans concentrating on their bad luck, perspiring like me because of the broken fans.

The game here is baccarat punto blanco. It’s played with eight decks of cards, dealt by three bankers. Each player is given two cards, traditionally by a “shoe” that moves up and down the table. Whoever turns the highest scoring hand wins the round. Cards two through nine are worth face value, tens and face cards — jack, queen, or king — are worth nothing and an ace is valued at one. Players calculate their hands by adding up the values then subtracting ten if that total is higher than ten. This is known as “modulo ten.” Nine is the highest value a baccarat hand can be. It’s called a “natural” and conquers all other hands.

Each table has an electronic board that displays the patterns of luck as mathematical trends. The crowds gather around these boards to decide which tables are lucky and which aren’t. They scrutinize the lines of numbers, which change minutely with every hand that is played at the table. It’s a way of computing the winds of change.

The waiter asks me if I would like another drink — a bottle of champagne, perhaps? There is a girl at the table and no one else. She looks over through her spectacles, and I see the look of a pro. She’s dolled-up in clothes from the malls in Tsim Sha Shui. Easy pickings, she thinks, looking at this plump gwailo in his gloves and bow tie like an outdated English tourist out on the town without his wife’s permission. She looks me over, and I enjoy the thought of skinning her alive with a few good hands. The bets are $50 HK a hand. I begin to smoke — Red Pagoda Hill or Zongnanhia, the stuff that kills — and we play. I begin to lose. Not ostentatiously or dramatically, but $50 by $50. The girl says her name is Shui Shui, and she asks me how I learned to speak Mandarin. It’s not every gwailo punter who can speak the mother tongue, she says, and I tell her I pick these things up. I speak languages in order to gamble.

I notice now her handbag, the kind you can buy in the markets in Shenzhen, faux Fendi with gilt metal that flakes away after a week. Her bracelet is one of those multicolored childish objects from the Paris Hilton collection. She must have seen it in a magazine — the small circles of enamel don’t suit her at all. She hoards her chips while her eyes scan the surface of the table as if it’s something she has never seen before. Then the rows of yellow numbers change, and I can hear them click, as if the luck force field is flicking them over like cards. The Shuffle Master ejects three cards apiece. Shui Shui handles them the way a customer in a market handles small fish before buying them. She looks over the top edges of the cards, and I see the crooked, up-country smile, the over-applied paints and creams. Is she a prostitute?

We play another hand at $100, and when the house flips over the cards with his pallet, I see that I have scored a baccarat, a zero. The girl shrugs and watches my chips move over to her. We’re now 7–0 in her favor. I stand up to go to the cashier for more chips. I have about two hundred US dollars left, and things are going badly. But the girl suddenly suggests that we go somewhere for the night instead of playing more baccarat. There’s little point in me losing more money, she says, since luck is against me. We can amuse ourselves with my remaining money, which will be just about enough. She says it as a joke, but she’s right.

We walk out into the lobby, and there’s a lilt in our walk, an agreement deep down at the level of the body. It’s not my favorite place, I say grandly. Have you been to the Venetian? I hate that, too, my tone implies, but at least you can get a decent drink. Oh, yes, she says. You can get a decent mojito there.

We walk out past the statue of Pegasus in the courtyard, and its wings are flapping, smoke coming out of its nose, and the whores standing about in the parking lot are laughing their asses off. We find a taxi to take us back to Macau. I suggest an older, colonial place near the An-Ma Temple, where I have not been before and where — for some reason it matters — I won’t be recognized.

The hotel lies at the top of a series of steep steps that wind around terrace garden patios with wizened trees and wet tables. As I close the door behind us, Shui Shui says she is not your usual prostitute. Not at all, she says. She’s a secretary at a real estate company, and she just wants to make a little extra on the side. She says she sends her money home to a small village in Sichuan called Sanbo. The monks of her local lamasery are gilding her deer on their roof, and she’s making merit by paying for them. So far she’s paid for the re-gilding of three deer. One customer per deer, she says, and it’s enough for a laugh.

After sex, as we lie in the dark listening to the rain, she asks me what I do, and I lie. I say I am just passing through. I like to gamble, I admit, that’s all. I don’t tell her that I’ve been here seven months playing every night and living at the Hotel Lisboa. I say nothing about my absurd compulsion. You must have a lot of money, she says, to stay in a place like this. All the other men run out of money. I win and I lose, I say, like everyone else. The odds against the punter in baccarat are a mere 0.27 so I can, in fact, break even. She says gwailo are all the same. We cannot give in to the goddess Guan Yin, deity of luck and sailors. If I could go with the flow, she says, I could win big. Gamblers, she says, are what the Chinese call hungry ghosts.

She says that Buddhists believe that the afterlife is divided into six realms. There is the realm of devas, or blissful gods; the realm of the animals and that of the humans; the domain of the asura demi-gods and that of preta, the hungry ghosts. Below them all lies the realm of naraka, or Hell. Each realm reflects the actions of a previous life. People who are reborn as hungry ghosts were strongly acquisitive, driven by desire. Their insatiable desires are symbolized by their long necks and swollen bellies. They are supernatural beings, continually suffering from hunger and thirst. Their huge bellies signify their crazed appetites, while their narrow necks suggest that they can never satisfy them. Their karma afflicts them in their rebirth. For Taoists, the hungry ghosts are the spirits of suicides and those who have died a violent death. During the seventh lunar month of the Chinese calendar, the hungry ghosts are let out of hell to roam freely, and the Hungry Ghost Festival welcomes them. The sacrificial altars of the Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva are arrayed with plates of flour, rice, and peaches. They say that’s what the hungry ghosts want to eat. It is a beautiful touch, that the ghosts crave peaches. As if the afterlife does not have them.

I dream about Shui Shui’s gilded deer. When I wake, she has gone, taking the “gift” I had placed on the night table before falling asleep. I go for breakfast at the Clube Militar, the old Portuguese officers’ mess, and eat a plate of baccalau asado and clam dim sum with a bottle of Perequita. I have $17 left.

The following night at eight o’clock exactly, I put on my darkest suit and take the elevator down from the seventh floor of the Hotel Lisboa. It’s the hour of the “second shift” in the world’s most profitable casino, and the revolving doors turn like turbines as crowds pour through them and disperse into the labyrinth. Seven million dollars a day in revenues and a pall of smoke that never moves, smoke that hits the throat like sawdust mixed with powdered metal. It hovers above the tangerine trees, from which a thousand red New Year’s envelopes hang like poisonous fruit. I go down to the hotel’s main mass-market casino, the Mona Lisa, where the games are endless in their diversity: pai kao, fanton, cussec, Q, and stud poker, and, of course, punto blanco, that dirty queen of casino card games. The boys bring me a sausage rolls and cognac, and I order a buttonhole from the Rua da Pessem. I lose again.

With $4, I play fish-prawn-crab dice for an hour — forgetting myself completely, winning a bit — then move off down the elevators to the Crystal Palace, which is like descending into an ice grotto. Glass shards are suspended from the ceilings in waves of green and orange. This is a place where the rational mind comes apart. From there I find my way in total solitude, arriving at the Club Triumph and the Lisboa Hou Kat, a place with a secretive feel to it, like a buried palace in Crete from the time of Linear B, with a circular room of leather sofas and more tangerine trees with New Year’s envelopes.

The hours pass. The money slips away. After a long losing spree, I go back to my room to freshen up and grab another $200, then take the elevator down to the casinos for a second try.

It’s nine now, and the evening shift is just in. Brutal, cynical men with red faces and cheap suits, with eyes that suck everything in and spit it out again. On the ground floor, they stand by the “throne of pharaoh,” a reproduction of a chair from Tutankhamen’s tomb, and a large vertical oil painting with its title provided: La Mère Abandonée. The painting depicts a woman with a lyre, sighing over a baby sleeping in a wheeled carriage. This scene of rural misery from nineteenth-century France fails to arouse their curiosity, and they turn their backs to it as they wait for the elevators. They carry bags of gaming chips and cans of winter melon tea. Their breath smells powerfully of oyster sauce.

I buy a cigar in the underground mall and go up to the Vvip rooms, where Renoirs loom on the walls. Here in the four innermost rooms, the bets are a minimum of $10,000, up to a maximum of $2 million. Three plays at a time, usually. There’s a separate entrance leading into the hotel so that the high-rollers are encouraged to roll right out of bed and gamble with sleep in their eyes. Here bright red armchairs are surrounded by Alma-Tadema paintings of ancient Rome, with gardens of laughing Nereids.

I play side baccarat for a while, and I’m impressed by the way the staff brings me my supply of chips. I cheer up as my luck improves; I win three hands out of six. Four hundred back in. I experience a stab of sadistic vitality. How bright is the world of money, the making of money from money.

It’s well after midnight by the time I get down to the new Sands, the first of the great American casinos, where one is guided by staff dressed in yellow Wizard of Oz uniforms. I’m feeling absurdly lucky as I am escorted upstairs to the Paiza Club, the most exclusive private gaming room in Macau. Here, I think to myself, I am surely going to experience the heights of ecstasy and torture. The style is very Chinese, so appropriate to this dawning age of Chinese capitalism, the coming golden age of Chinese money. Terra cotta jars in niches and dragons everywhere. The world’s biggest chandelier, my escort says, indicating with her hand. I am then given a choice of private rooms with fires in grates, blood-red panels, and gray tables. I choose a room where I can play against the bank alone with $10,000 HK hands.

It is now that I feel the compulsion. A sensual moment, charged with anticipation, the mind emptying out, scurrying like a wingless bug. The gambler is a man attuned to the supernatural. He is wary of portents and omens. He is perpetually on edge.

The dealer bows. Do you like the cards? he says. Special from Germany. Binokel with Württemberg artwork. I feel sweat moving slowly down my back, clinging to the spine, an area of moistness developing between my eyes. I think of Guan Yin. Her name means “listening to the sounds of the world.” For the Taoists she is an immortal, and I pray to her. But she’s not listening, the bitch, and I lose everything in eight minutes.

Stunned, I get up, thank the bank, and leave. I am now functionally destitute. I walk back to the Lisboa in the dawn, past the yawning molls of the Rua de Pequim. The sky is lit with contorted neon signs for massage girls. Suzie, Babylon Girls, Mega. Inside the Lisboa lobby I wander in despair around the shopping galleries, staring at those antique inkstones and Chinese seismographs that seem to be permanently on sale. There is a gilded peacock from Garraud’s of London displayed with a glass of blue wine next to it.

Soon, because I’m an addict, I feel the itch returning, and I think of the seventy dollars still in my room, which I could use right now in one of the Lisboa casinos. If I lose it, of course, there’ll be no breakfast tomorrow morning, and no lunch either. I’ll be begging my gambler friends on hands and knees for small change. I go up to my room and pull the notes from under my mattress. I stand there in the middle of the room, shaking. A play or breakfast? I throw the money down and weep, then take a long hot bath. I am shaking even in my sleep.

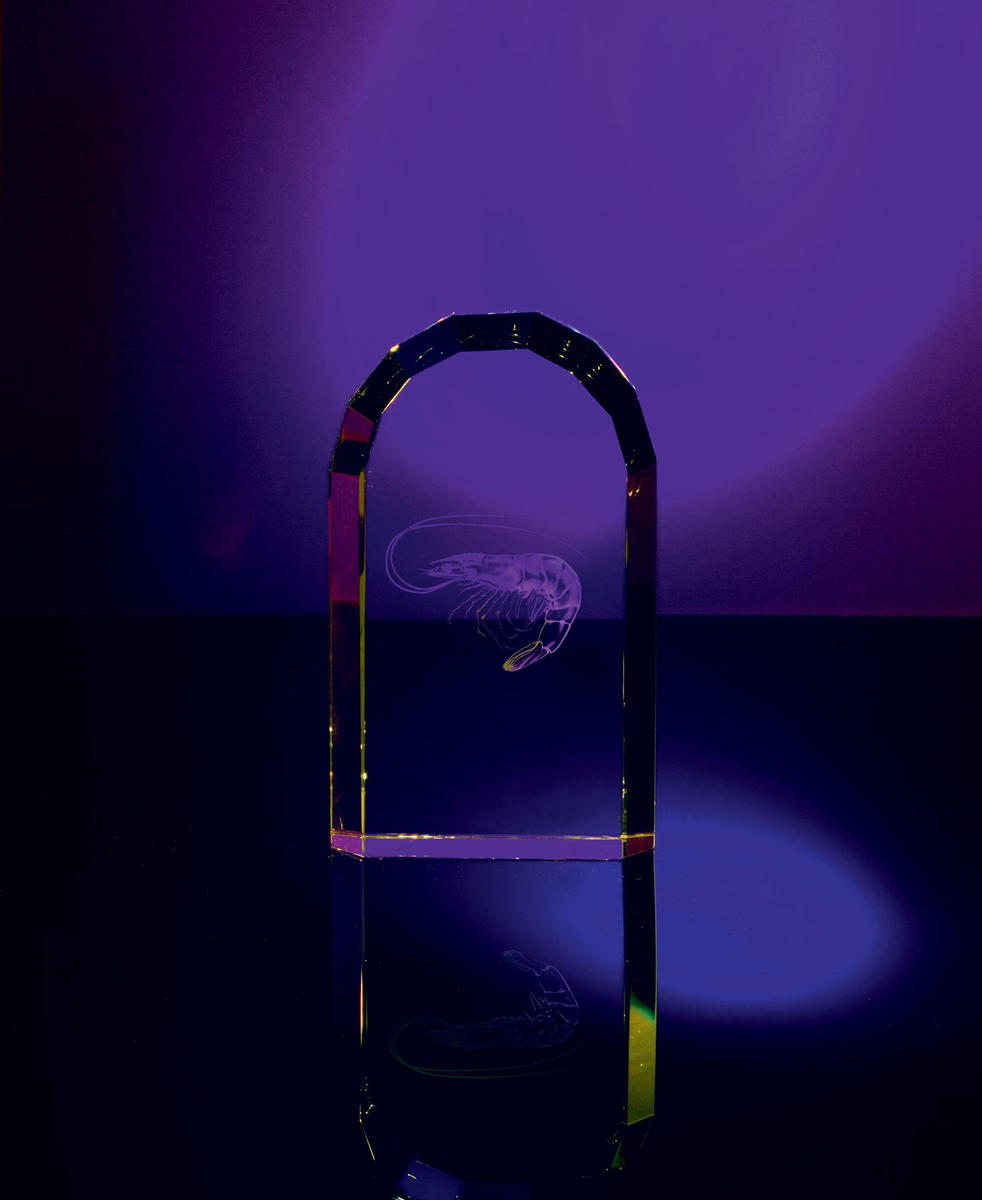

The next day, somewhat calmed, I change into a different suit, one of my many cheap suits from Bangkok, and I feel something in the pocket of the old pants that I hadn’t noticed previously. It’s a small jade charm on a chain in the shape of a deer. It must have been put there by Shui Shui, while I was asleep. I hold it fondly between my fingers and turn it back and forth. That girl. I can barely remember her now. The jade is worn and smooth, it might be hundreds of years old. I wonder why she has made me such a gift. Perhaps she felt sorry for me. I put the chain around my neck. I feel exhausted but determined as I make my way downstairs.

I walk for a while down long Reppublica, which is like a boulevard in Lisbon or Madrid, to the far end where the ferries and cruise ships dock, and to the tail end of Felicidade, or Happiness. The brothels used to be here, but now Felicidade is filled with tea shops, which I suppose is another kind of happiness. Endless side streets are arranged like a jigsaw puzzle. I circle back to a small church I love that lies at the top of the Travessa do Bispo and sit there with my dripping umbrella, trying to clear my head, praying for luck.

That afternoon, I decide to go to the Grand Emperor, one of the gaudiest of the Macau houses. It’s conspicuous for its gilded replica of the British royal state carriage by the front doors and for the Beefeaters in fur hats in the gold vestibule. There is something in this kitsch that reminds one that there is more to being alive than being alive. It’s like some Hans Christian Andersen fairy palace as imagined by a small child with a high fever. I pass under an imposing but strangely sympathetic portrait of Queen Liz and another of the Duke of Cumberland — a bad-looking motherfucker, if I may say so — and I finger the $1000 note I am going to use.

I take the escalators up past floor after floor decorated in the theme of European aristocracy. I settle for the Venetian floor, with myriad images of the age of Casanova, swooning inhabitants of boudoirs, weeping over handkerchiefs, and candlelit gallantries around baccarat tables. I sit at a table of fourteen mostly young and indolently thuggish men in leather and velvet jackets with wide lapels, like the accoutrements of famished princes. I begin to win.

I win a natural, a perfect nine. Then, on the very next hand, I win a second natural. There is a low exclamation — drawn-out, animal — around the table, and the three bankers shoot me incredulous looks that could have been synchronized by puppeteers. I rake in the chips. These consecutive wins suddenly induce a mood of superstitiousness in the entire room, and I notice the tables thinning out as people migrate to mine. Success is irresistible. It’s like a crime scene, something that enchants the worst side of the mind. I play on and on, winning by naturals for six hands in a row. Spectators begin to swear. Zau gei! I make four thousand HK in sixteen minutes. Then eleven thousand. The bankers perk up.

It is said that in 1897, a wheel at the Monte Carlo Casino rolled eighteen reds in a row, and a German gambler made a small fortune on the eighteenth because nobody else around him dared bet on red. That man held his nerve. I do the same, cash my chips, and leave. I walk out like Nero among his ruins.

It goes on like this for several days. I go out every night with splendid confidence and clear out a few tables. I go to the Landmark in the early hours to play amidst that Ancient Egyptian decor and then have a gin and tonic at the bar, which is shaped like a Nilotic barge. I try smaller casinos I have never been to before on the high floors of nondescript skyscrapers. I go to the Fortuna and the Hong Fak. I get richer and richer for about a week, and I cannot fathom how it’s come about. Luck is just like that. You reap it while you may. When I go home to the Lisboa, I lock the door and listen to music. I go for walks to Vulcania, the reconstruction of a Roman city that sits on the edge of the waterfront, with a fiberglass Colosseum and centurions in full armor who raise their arms and cry “Hail!” As I walk by, they salute and offer me instead of the usual “Hail!” a slangier Cantonese greeting with a dash of English: Gum lei take care la.

Flush with cash, I eat at the Galera restaurant on the sixth floor, where Joel Robuchon holds sway for the Lisboa’s owner, the billionaire developer Stanley Ho. Ho at eighty-nine is a wine collector, a ballroom dancer, a former gunrunner, and a marvelous cad. The Lisboa is his bad dream. There are stars on the ceiling that turn on and off and stuffed petrels sitting stiffly on silver perches. I eat an almond soup sprinkled with purple gorse flowers. There, one evening, over a bottle of Kweichow Mountain 1927 (at $47,000 HK, the most expensive Chinese wine ever made), I spot a small item at the bottom of page 16 of the South China Morning Post. It’s one of those items that I am naturally drawn to, small tragedies in large cities. This one tells of a suicide in an apartment block in Jardine’s Bazaar in Wan Chai. A secretary at a real estate agency has hanged herself with a light flex in her fourth-floor walk-up studio. Her age is given, her name withheld, but it says she was an avid gambler and had lost a lot of money in the Macau casinos.

It stops me cold. I put down my glass, and I find that my hand is shaking. I feel myself losing any sense of where I am. I know that it is Shui Shui. Then I look up at the top of the paper — it’s dated January 14, last week. Counting backward I realize that this is only three or four days after our night together. I pay the bill and go back to my room. I collect all the cash stashed there and put it into two Adidas bags, then take a cab to the Venetian.

The Venetian is the world’s largest casino, and its baccarat tables are set in columned halls with fountains and frescoed ceilings and cypress trees. Parts of it are like a baroque church, with glassy marble floors. Actors dressed like characters from a Puccini opera wander about, breaking out into arias or ringing bells and turning cartwheels among Taiwanese tourists who are anxious to capture them on film. I have a few drinks at Florian’s, then make my way to the center of the gaming floor.

I sit and ask for a glass of naughty lemonade, which is served at all the tables. I feel tipsy as I ask to join the game. I’ve already converted my cash into a considerable pile of chips. When I say that I want to bet all of it, they ask me if I’m certain. I say, Sure, why not, I’m in the mood to bet all of it. They ask me a second time, as if the sheer size of the bet is a hazard to me in some way. A manager comes across and says that a bet of this size would not normally be permitted, but if I insist, he can request clearance. I say, Go for it. I say I’ve had a good week and I have chips to burn. He bows slightly and smiles. Very well, sir, he says. Just let me call up.

Within minutes the matter is settled, and I’m told I can bet whatever amount I want. It is a remarkable privilege. It is perhaps because I am a gwailo and have been known to suffer the ups and downs of baccaratic fate.

I ask the dealer to play. As the highest better I have the right to the first two cards. Just before play starts, however, I halt the proceedings and take back 20,000 of the chips and return them to my bag. This act of prudence is warmly approved as very Chinese in spirit, and the dealers ask me again in Cantonese if I’m comfortable with the bet as it now stands. I nod. I have finally become, I think, a true Chinese. I feel the winds and the gaze of the Bodhisattva and the ghost of the dead woman hanged in her miserable apartment in Wan Chai. I am in the realm of the hungry ghosts, and I know how to get out of it. I am certain that these supernatural presences will not let me lose. They are looking over my shoulder, protecting me, directing the flow of luck.

I turn the cards and — supernatural or not supernatural — it’s a baccarat. The losing zero. There are no ghosts, after all. I hear voices whisper, the gwailo just lost everything! The crowd is silent for a while, contemplating this awful fact, which might have happened to any one of them. Then they begin to laugh, to guffaw, cigarette smoke steaming out of their nostrils. It’s the laughter of bad faith, but also of relief. Theirs, and mine. Baccarat, baccarat! The poor bastard gwailo lost it all! Luck has come, and luck has gone away.

I am not in the slightest bit disturbed. In fact, I am happier than I have ever been. I pick up my bag, thank everyone concerned, and walk out of the casino as if nothing has happened. I walk back to the Lisboa through a freezing drizzle. I pay part of my outstanding bill there and keep back a few dollars for the next day’s play. Then I go to sleep in my room with the aid of a few pills. The nightmares come back, but I know I can survive them.

The following day I ask the receptionist to post a letter to the monastery in Sanbo, in Sichuan. I put 10,000 into the envelope and seal it without any note of explanation to the good monks of that far-off place, which I will never visit. I hope it will be enough to re-gild the remaining deer on their hallowed roofs. I turn then and walk to the escalator that will take me down to the Mona Lisa. I have seventeen dollars for the first play, plus enough for breakfast at the Noite e Dia Café in the basement, where I can watch the dog races on TV all day long and where I will be served by tall Mongolian girls dressed in pale gray leather capes. In the bright glare of the relojerias and the pharmacies rich with cellophane-wrapped shark fins, I will feel a great love for the hungry ghosts, and when I pay the bill, I will leave Shui Shui’s jade charm alongside the crumpled banknotes and the little sign that says “Thank You” in English.