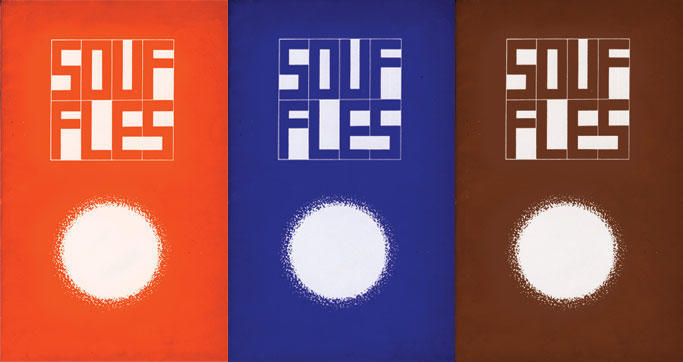

In 1966, a small group of Moroccan poets, artists, and intellectuals launched Souffles, a quarterly review that would over time become at once a vehicle for cultural renewal and an instigator of efforts to promote social justice in the Maghreb. From its very first issue, Souffles was a unique experiment, a Moroccan and Maghrebi effort to liberate the country’s intellectual framework from fetid provincialism and lingering colonial complexes. It was a cri de coeur, a rebellion against the artistic status quo, a manifesto for a new aesthetics, even a new worldview. Its trademark cover, emblazoned with an intense black sun, radiated rebellion.

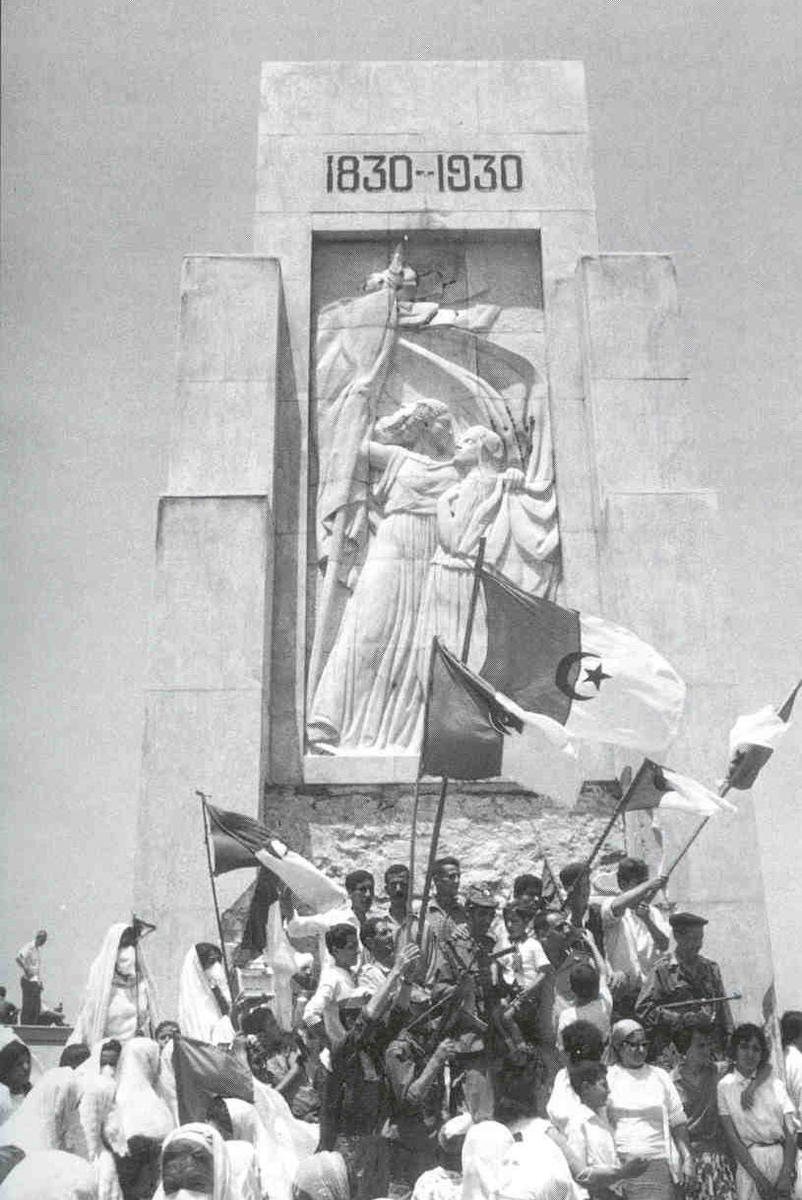

A decade earlier, the French protectorate of Morocco had managed to secure its independence as a kingdom while Paris concentrated on retaining neighboring Algeria, where a war of independence was just beginning. Muhammad V, Morocco’s new king and former sultan, and the unlikely hero of the nationalist movement, began to consolidate political power against the backdrop of the Cold War. Leftists battled conservatives for control of the nationalist movement, while Crown Prince Hassan maneuvered to position himself as the ultimate political arbiter of the young country. When his father died in 1961, the prince became King Hassan II.

For Moroccan intellectuals, students, and urban workers, the Sixties were a time of massive upheaval. Thousands participated in strikes and street protests that often ended in brutal clampdowns, arrests, and torture. Leftist political leaders such as Mehdi Ben Barka (who was assassinated by the regime in 1965, probably with French and American help) built links with progressive forces abroad, including Che Guevara, Amilcar Cabral, and Malcolm X. In neighboring Algeria, in Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and countless African, Asian, and Latin American countries, progressive forces were associated with socialism or communism while “reactionaries” sought the backing of the US or former colonial powers.

Into this fraught picture entered Abdellatif Laabi, founder, editor, and publisher of Souffles. The son of an illiterate saddler from Fes, Laabi, like many of his collaborators, was a member of the petite bourgeoisie — neither of the country’s elite nor cut from especially humble cloth. He had attended colonial schools and taught French. His early poems combined surrealist invective and a rage against his own uprootedness as a Moroccan who was more comfortable expressing himself in the colonial lingua franca than in Arabic. Laabi launched the inaugural issue of Souffles with this prologue:

The poets who have signed the texts in this issue-manifesto of Souffles are unanimously aware that such a publication is an assertion on their part at a time when the problems of our national culture have reached an extreme degree of tension.

The current situation does not, as some may believe, speak of a creative proliferation. The cultural agitation that individuals or organizations would like to pass off as a growth spurt of our literature is in fact the mere expression of a cultivated stagnation, of a certain number of misconceptions as to what the real sense of literary activity consists of.

Petrified contemplation of the past, sclerosis of form and content, unashamed imitation and forced borrowings, vainglorious false talents — these are the tainted daily ration with which the press, periodicals and the greed of all-too-few publishers have bored us stiff.

Not counting its multiple forms of prostitution, literature has become a form of aristocracy, a badge of honor, a manifestation of intellectual prowess and do-it-yourself attitude.

Laabi continues:

Something is afoot in Africa and in other Third-World countries. Exoticism and folklore are falling by the wayside. No one can predict where this will lead. But the day will come when the real spokespersons of these collectivities really make their voices heard, and it will be like dynamite exploding the rotten arcana of the old humanisms. Severe patience and strict self-censorship were necessary to produce this review, which sees itself first and foremost as the organ of a new poetic and literary generation._

Souffles was not created to add to the number of ephemeral reviews. It answers a need that has never ceased formulating itself around us.

That essay, like several that would follow, lashed out at the bourgeois literary salons that wallowed in nostalgia for a colonial order and its Gallic canon, which was an integral part of France’s mission civilisatrice. Although a few Moroccan writers and artists had been promoted internationally during the colonial era, they were chosen for their exotica: ochre walls and minarets, Berber tribes and ornate handicrafts — the stuff of cruise ship advertisements.

A major intellectual reference for Souffles was Franz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, as well as early postcolonial writers — Aimé Césaire, Mario de Andrade, and René Depestre — and journals like Présence Africaine. The art critic Abdallah Stouky would, for instance, write on “nostalgia for Negritude” (of the Senghorian variety) at the Dakar International Festival for Negro Arts in 1966, accusing the organizers of fabricating a false “negro unity” based on the European enthusiasm for “primitive arts” that had been set off half a century earlier by artists such as Pablo Picasso and Matisse. Exoticism, as Franz Fanon admirably stated, “is a form of racist simplification. From that perspective, no cultural clashes can occur. On the one side there is a culture in which qualities of dynamism, growth, and depth are recognized. A living culture that perpetually renews itself. On the other side there are characteristics, curiosities, objects — but never structures.” In a later essay, considering his own poetic evolution, Laabi would cite Fanon and other critics of colonialism, espousing their ideas as a model for his own efforts of “de-alienation and restructuration, [of] struggle against cultural domination and imperialist ideology.”

Abdelkebir Khatibi, a novelist and sociologist whom Roland Barthes would later cite as an influence, was perhaps emblematic of the concerns that ran through the pages of Souffles. An essay he penned in the journal’s third issue would eventually lead to his controversial Le Roman Maghrébin (The Maghrebi Novel). The original essay was titled “The Moroccan Novel and National Literature” and published in the summer of 1966.

Let us consider now, not the problem of literature, but that of Maghreb writers. After the second war, the first group (Feraoun, Dib, Mammeri, Sefroui…) focused on describing local society, on establishing a relatively accurate portrait of its different social strata, in other words to say “here is who we are, this is how we live.” It has been said that this literature was first and foremost a testimony of an era and of a specific situation. In a sense, this description was salutary because it was already a type of appraisal of the colonial situation. But at this very level, it was already being overtaken by events that were taking place in North Africa. For instance, at the moment when Algerians took to arms to liberate themselves through violence, novelists were busy describing the minutia of everyday life of Kabyle villages and poets were singing the anxieties of their torn personalities._

Condemned to follow a reality that is in permanent transformation, the writer faces a dilemma: if he wants to follow the evolution of this reality in a continuous manner, he becomes a journalist. If he takes too much distance, he risks ending up producing disembodied literature. At every instant, an uneasy self-awareness (“mauvaise conscience”) risks to ensnare the Maghrebi writer.

The situation has become more complicated after the Algerian war. Some writers (Haddad, Djebar, Bourboune, Kréa…) tried to put their literature in the service of the Revolution. In their way, they helped to make the Algerian problem known. Unfortunately, for the most part this literature has outrun its course, it died with the war. Now that we face enormous problems of nation-building we must ask frankly and without detours the question of literature: in countries that are in large part illiterate, that is to say where the written word has few chances for the moment to transform things, can you liberate a people with a language that they do not understand?

The debate over language continued to be at the core of the early issues of the magazine. The Soufflites were aware that publishing in French, the language they had been educated in and through which they could reach an intellectual elite (in France and elsewhere), was limiting the size and scope of their readership. Although after 1968 Souffles would develop an Arabic-language edition, Anfass, the question of language would remain paramount — and not only for the Moroccan avant-garde.

Only a decade after Morocco’s independence, Laabi wrote of the linguistic anxiety of an entire generation of middle-class Moroccans who were raised with two languages, but who too often had mastered neither. In the fourth issue of Souffles, he expounded on the problem:

Thus, it is true that the linguistic frustration of the colonized went beyond, in the colonial context, the simple coexistence of two modes of expression. It weakened the psyche of the colonized and was a weapon for the depreciation of his own culture.

At the level of this repressive phase, the linguistic dualism was a tragedy. A tragedy that has not been overcome for many intellectuals of the independence period since even the cultural structures conveyed by the new modes of education and the improvised experience of arabization have not, in this domain, shattered in depth the basis of the colonial status quo. Not only does the problem remain whole but the new policies to recast education have led to a hecatomb with regards to adolescents’ command of a language of expression. The colonized adolescent, even if he was deprived of his maternal tongue, could still dispose of a vehicle for his thoughts through which he could express his rebellion, his ideas, one through which he could exteriorize his personality. The post-independence adolescent has lost this imposed vehicle but has not yet re-conquered the other. He is aphasic. His thought, his deep personality, only emerge in sporadic, imprecise scraps. His linguistic infirmity does not come from a conflictual position, but rather from the imprecision of his methods, from the uncertain negotiations in this phase of evolution or from the stagnation through which most newly independent countries go through. The tragedy has thus changed in nature — it has deepened.

Laabi would settle early on the question of whether there was any possibility of a “legitimate” language for the poet. For him, the question was not whether Arabic was better than French, but rather, how each language could be re-appropriated. “A poet’s language is first and foremost his own language, the one that he molds and shapes out of linguistic chaos, as well as the manner in which recomposes the fragments of worlds and dynamics that exist within him.” The far more pertinent question was how to carry out that recomposition.

Questions of cultural decolonization would continue to dominate Souffles in its early years, both in the essays Laabi and others wrote about literature, the plastic arts, education, and other topics and in the poetry that was the publication’s main feature during this period. Souffles would become a launching pad for many of Morocco’s leading contemporary poets and novelists. Along with Laabi himself, Mustafa Nissaboury and Mohamed Khair-Eddin contributed; the three are probably Morocco’s best-known poets, although that fame is mostly restricted to the French-speaking world. They initially wrote in French, but with the advent of Anfass, some poems, such as Nissaboury’s “Manabboula,” were republished in Arabic or even rewritten.

Souffles offered younger poets an opportunity to reach a larger audience than other publications coming out of Morocco at the time, particularly as it had captivated the attention of French intellectual circles who, caught up in the enthusiasm over decolonization and an emerging nonaligned movement led by third-world countries, publicized the new Moroccan literature to a wider Francophone audience. Tahar Ben Jelloun, perhaps the best-known contemporary Moroccan writer internationally, was among them. Ben Jelloun began writing in Souffles in 1969, a few years before he published his first novel. In “Planet of the Apes,” his first published poem, Ben Jelloun articulated the same identity issues Souffles had initially raised (notably, the interiorized Orientalism among Moroccan artists and writers and their pandering to French tastes for exotica), but combined them with a more violent critique of Western consumer culture:

The Club Maméditerranée is your salvation

French atmosphere guaranteed, demanded,

or your money back

Climb atop some dromedaries

your vertigo will be in the image

of your churning hunger;

your mouth will open to footnote

ruin and tears;

In the morning drink a little Arab blood:

just enough to decaffeinate your racism;

To your friend offer your tattooed souvenirs

a postcard of aluminum beatitude

obscure resonance of our morgue-skull;

And then fuck an Arab

he is natural, a little savage

but so virile…

Morsels of uprooted flesh will

remain

Dangling by a thread

to your shameful memory

You will no longer be able to drive him

out of your phantasms

He will ejaculate humiliation and rape

onto your face

Wounded

you will gather under the tamed trees

you will watch the stars dissolve in your

facile dreams

the fever will rise and you will spit blood

onto your good sentiments

the carrion will come to crucify you

in the shade of the wonderful sun of the

Club Maméditerranée

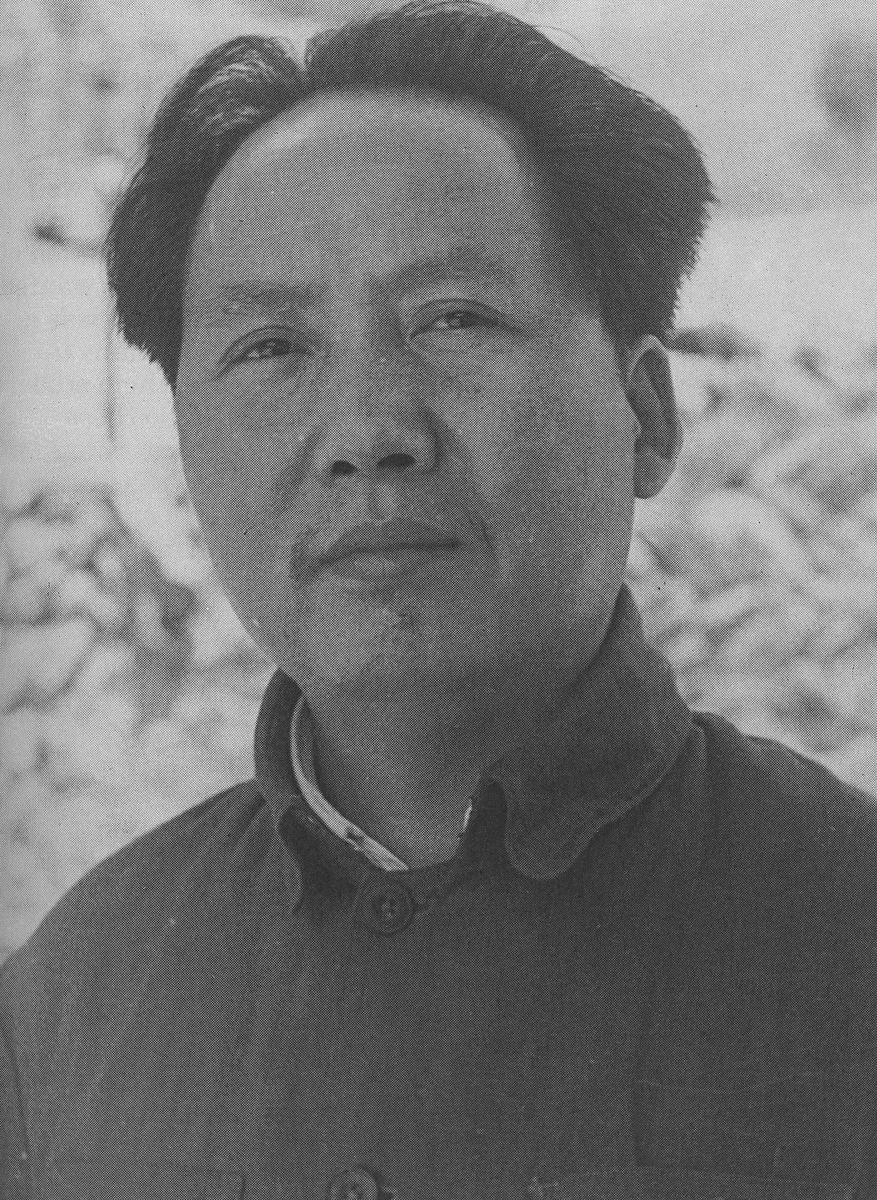

“Planet of the Apes” captured what Souffles was fast becoming: a firebrand publication that was more explicitly politically militant in the wake of the catastrophic Arab defeat of 1967 and the events of May 1968. The magazine grew more explicitly invested in the Palestinian plight, more critical of French influence (notably Francophonie, France’s cultural policy towards its former colonies) — more militant generally, forging links with the American Black Panther Party (some of whom were living in exile in Algiers), Egyptian communists, Chinese Maoists, and radical African and Latin American movements. This led to some unfortunate choices, such as the publication of a defense of Mao’s Cultural Revolution and Enver Hoxha’s Albania.

Souffles’s editorial team could not help but be influenced by the leading debates of the day, notably over the Palestinian question. But the primary engine of the magazine’s political turn may have been the arrival of Abraham Serfaty, a firebrand mining engineer who would come to lead Morocco’s radical left and turn Souffles into its mouthpiece. Serfaty was born in Tangier to a middle-class Jewish family; during his engineering studies at the elite Ecole des Mines in Paris he joined the Communist Party. Upon his return to Morocco, he linked up with local communists and joined in the nationalist movement, earning him a six-year exile courtesy of the French colonial authorities. He returned after independence, and his education put him in high demand; he held posts in the Ministry of Economy and was a key architect of Morocco’s policy at the Office Cherifienne des Phosphates, the state mining company. By the late 1960s, however, Serfaty was at the forefront of a wave of strikes by miners and other workers. He was fired from his ministry post in 1968.

Serfaty met Laabi in early 1968 during political debates on the Palestinian question. Between this period and 1970, he slammed the door on a Moroccan Communist Party he found too ossified and created, with Laabi, the Marxist-Leninist movement Ila al-Amam (Forward).

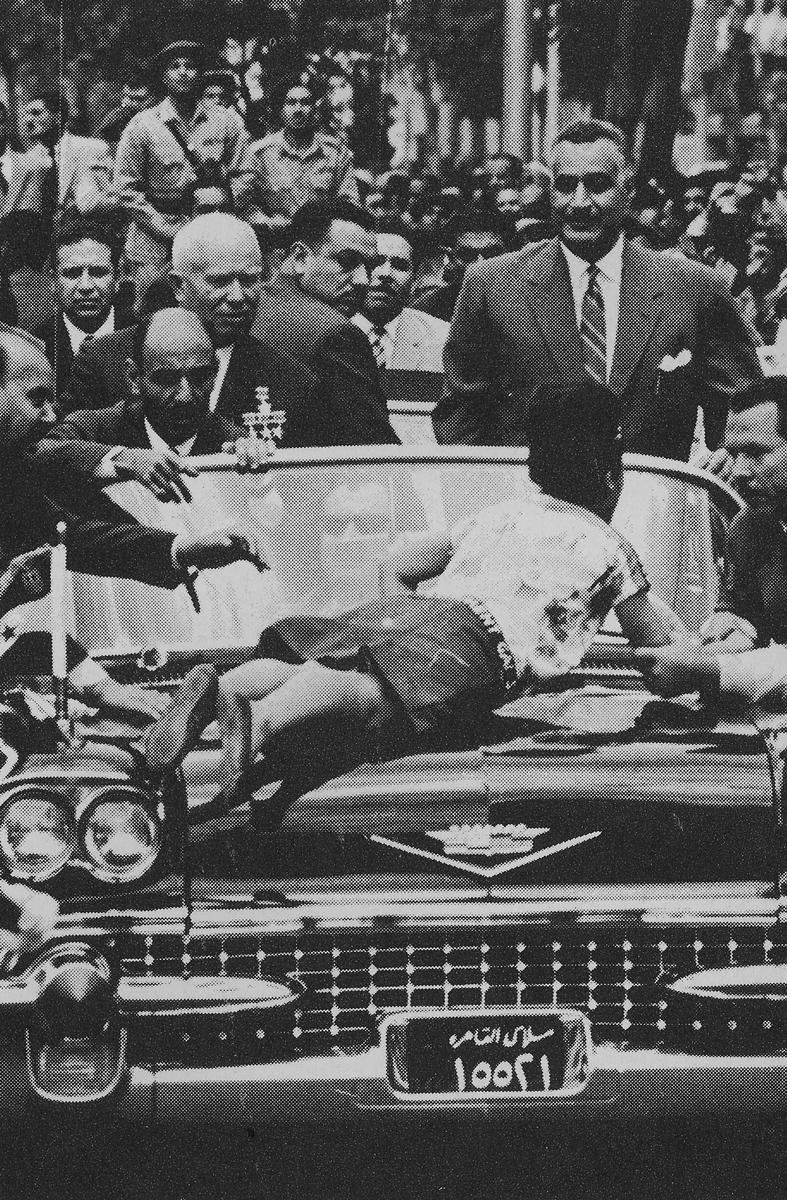

Under Serfaty’s tutelage, Souffles’s poetry section shrank in favor of articles about educational policy, industrialization, the relationship between capitalism and imperialism, the Arab-Israeli conflict, and the international banking system. This was not always to the taste of the review’s early contributors, poets who felt they had nothing to say about the mechanization of agriculture or the Rogers Plan. Indeed, poems by Nissabouri and Khair-Eddin slowly disappeared from the pages of Souffles. Even Laabi’s poetry took on a tone more explicitly linked to events of the day. “The Call of the Orient” was a poem published shortly after Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser’s death:

I saw Damascus Beirut

mourning

but it was not the mourning of Jerusalem

that covered the walls of Damascus and

Beirut

the inscriptions spoke of a man

ignored the land

and Jerusalem its womb

Damascus Beirut

in simian and tragic lines

behind the symbolic hearses

of the last pharaoh

fallen under the blows

of overwork

and of Remorse

Jerusalem bled

and suddenly

attacked by a mirage

reappeared on the other side of the Jordan

similar and yet different

Amman relieved it

so colossal was the massacre

In 1969, the changes Serfaty had brought to Souffles became even more evident with the publication of a special issue on Palestine (including an article by Serfaty distancing Moroccan Jewry from Zionism). The layout of the magazine changed, too. Gone was the abstract, blazing dark sun that had graced every cover since the first issue in 1966; instead Souffles became wider, thicker, squatter. Its covers featured pictures and illustrations.

The social and political crisis of Morocco in the early 1970s — massive labor unrest, political disenchantment with mainstream parties, rampant corruption, and the increasing autocracy of King Hassan II — had helped transform Souffles from a literary review into the country’s foremost political newsletter. In 1970 and 1971, years of permanent strikes at many universities and high schools, students held teach-ins where the latest Souffles served as textbooks, its articles templates for discussion and debate. It was not a magazine that one bought and read in one’s living room or at the café; it was a manifesto for a young and diffuse political movement.

Souffles’s new political direction, its association with Ila al-Amam, and the central role it played among the revolutionary student movements — which had adopted Laabi and Serfaty as intellectual leaders — would soon land the publication in trouble. Issue number 22, published at the end of 1971, featured an essay by the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine titled “Toward a Democratic Solution to the Palestinian Problem” and another by Serfaty dismissing “democracy” and “dictatorship” as petit-bourgeois concepts. It would be the last to be published. In the first few days of 1972, Laabi and Serfaty would be singled out by the Moroccan security services as a driving force of the student movement. Serfaty remembered the day of their arrest in his memoirs:

It was that early in the morning of Thursday 27 January 1972 [that] the police came to get us at our respective houses, Abdellatif and I, to take us to the central police station of Rabat where we were, separately, immediately submitted to torture. It was the first time. I had received beatings and very hard blows when arrested by the colonial police, but torture is another ordeal. It’s not even fear of death: in December 1952, I had received blows that could have shattered my skull but had not said a word. Torture is a form of debasement that any being rejects, with a refinement in pain that horrifies much more than the naked specter of death. If one is not prepared to sacrifice one’s life for one’s ideal, one gives in from the first few moments. But there is worse: torture makes one mad, in [that] it is in this abyss of insanity that one risks losing all self-control, and thus to betray oneself by talking.

Their release was in part possible thanks to students who took to the streets in droves (often brandishing copies of Souffles) to demand their freedom. Laabi was subsequently rearrested and sentenced to ten years of prison for crimes of opinion. In 1980 he was released but forced into exile to France, where he still continues to write. Serfaty went underground shortly after the first arrest and spent two years hiding in safe houses, where he continued to devote himself to Ila al-Amam until the police caught up with him. He spent the next seventeen years in jail serving out a life sentence (on a charge of “plotting against the state’s security”) before also being exiled to France. Serfaty was one of several prominent dissidents who returned to Morocco after the death of King Hassan II in 1999, when he was made an advisor to a state-run oil exploration institute. He is now retired and severely ill.

Shortly after Souffles was banned, General Mohamed Oufkir, Hassan II’s right-hand man, ordered fighter pilots to shoot down the royal jet. They failed, and Oufkir was killed and his entire family imprisoned. It was the second coup attempt in a year and would usher in over two decades of repression and fear, the so-called années de plomb (“years of lead”) during which political and press freedoms were severely restricted and Hassan II’s political opponents systematically destroyed.

In recent years, with slightly greater press freedoms afforded by Mohammed VI, there has been a wave of new periodicals. Some, like Le Journal, have produced trenchant critiques of Morocco’s hesitant democratization under the new monarch. But in the thirty-five years since the demise of Souffles, no publication has matched its stature, appeal, or intellectual authority. The debates it inaugurated-on education, language, identity-are with us still, albeit in new configurations. Ironically, the postcolonial environment that Souffles emerged out of, centered on North Africa’s uneasy political and cultural relationship with France, has now almost entirely been replaced by a more uneasy relationship with American political and cultural power. And the inheritors of the humanistic legacy of Souffles face fresh opponents, most notably from Islamists. Nichane, a new secular-minded news magazine printed in darija, Morocco’s dialect, was banned in early 2007 for printing jokes about the prophet Mohammed. The editor of Nichane, novelist Driss Ksikes, was so embittered by the episode that he resigned. Since then Ksikes has been dreaming up a new cultural review whose inspiration will be the early Souffles, with a focus on the arts and literature rather than the often tawdry and convoluted turns of the Moroccan political scene. As to the later, combative, political Souffles? Time will tell.