New York

Iran Inside Out

Chelsea Art Museum

June 26–September 5, 2009

The story began, as good art narratives so often do, with a toilet in a museum. A well-placed reference to Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 fountain has served as an anchor of credibility for many a flighty art show. But ‘Iran Inside Out,’ which brought together recent work by fifty-six Iranian artists at a particularly opportune moment in Iran’s political history, pulled out the stops in terms of cross-cultural references. And when it came to sexual puns and biting humor, these Iranians gave the old Frenchman a run for his money.

The urinal in question was Behdad Lahooti’s A Cliché for Mass Media, an Iranian-style toilet printed with Farsi words from classified ads: “housing,” “resources,” and several iterations of “youth.” The cliché of the oppressed young Iranian artist may be just about as well worn as that of the urinal in the museum. But Lahooti, like many of the artists in this show, knowingly manipulated stereotypical expectations of contemporary Middle Eastern art. The toilet included the artist’s cellphone number, and noted that he was accepting “advertisements” and “sculpture commissions.”

The strategic ploy that critic Tirdad Zolghadr once gleefully advocated as “ethnic marketing” was in full force here. One gallery space was declared a “Culture Shop,” with a “Special Sale on Stereotypes.” Shirin Aliabadi and Farhad Moshiri’s Operation Supermarket series, showcasing such goodies as Intifada laundry detergent (“rough action needs tough action!”), set the standard. Pooneh Maghazehe wore her handcrafted outfits — equal parts Persian folk whimsy, Amish pilgrim, and Star Trek send-up — during her documented performances in American supermarkets and Laundromats.

Art that claims to speak of lands far, far away is inevitably viewed as culturally representative, and the artists in this show rose to the challenge with varying degrees of cooperation, cooptation, and resistance. Conceptual tactics were interspersed with paintings and patterns. Farideh Lashai, long known for her vivid modernist abstractions, presented an ambitious painting-video triptych that married Édouard Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe to Orhan Pamuk’s My Name Is Red. Established painters such as Lashai and Nicky Nodjoumi lent weight to the proceedings, and videographer Shirin Neshat was an obvious choice, but Kamran Diba — better known as the architect of Tehran’s Museum of Contemporary Art and its first director in the late 1970s — made what was an unusual public appearance for the éminence grise. Diba’s 2007 photographs of camouflage-painted dolls could have been a response to the aesthetic trajectories of a younger generation, paired as they were with Arash Hanaei’s 2004 series Abu Ghraib or How to Engage in Dialogue, tiny backlit photographs of hooded and handcuffed plastic action figures.

Galleries were packed, salon style, with work — their presentation constrained, most likely, by temporal, spatial, and budgetary limitations. But the catalog made amends, giving ample room to reproductions, texts by the artists, and statements from their galleries. Interviews with gallerists and collectors provided a pragmatic introduction to the ways and means of the Middle Eastern art scene. Veteran New York gallerist Leila Taghinia-Milani Heller wrote of how she talked curator Sam Bardaouil out of his initial idea of showing just fifteen artists, throwing herself wholeheartedly behind a project devoted to “Iran the country, the nostalgia, the statement… Didn’t I tell you Iran is a statement?”

But the artists’ statements were the key to the work. Vahid Sharifian’s entry was a day-in-the-life story, wherein he woke and fielded emotional IMs, sensationalist journalists, and a Dubai collector who was convinced he had Andy Warhol’s number (“I gave him my aunt’s number who is looking for a rich husband”), all before his morning cigarette. Sharifian’s series of digitally manipulated photographs, Queen of the Jungle (If I had a Gun), were oedipal and political metaphors that were as courageous as they were hilarious. Wearing nothing but an afro and sheer underwear, the artist humped lions, breathed fire at eagles, and indiscriminately toyed with sacred symbols both local and global.

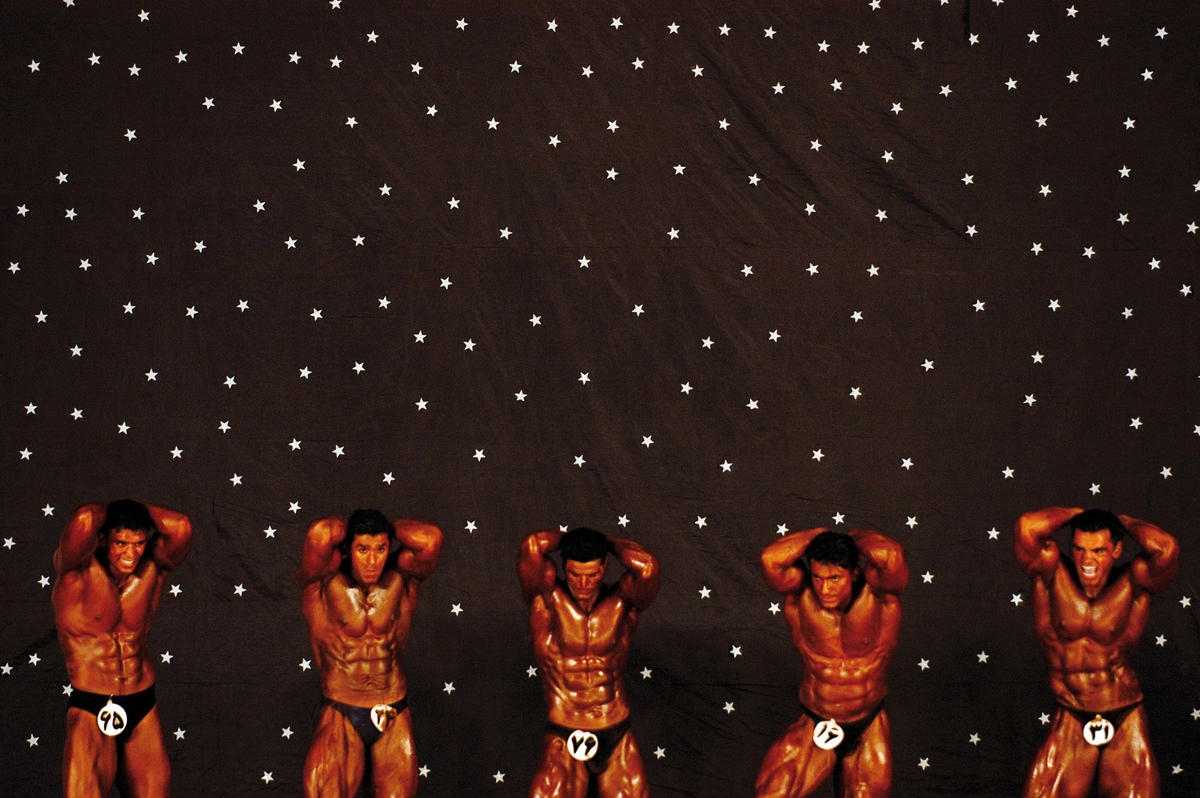

The exhibition was strong on work that treated sexuality with unprecedented frankness, from the cheeky vulgarity of painted female bodies to the homoeroticism of reinvented heroes. Siamak Filizadeh’s cover designs for No!, a fictional Middle-Eastern celebrity magazine following characters from Iran’s revered epic poetry, was a perfect case in point: they turned mythic hero Sohrab into beefcake coverboy “Sohrab Joon,” speaking for youth with campy pop-cultural bravado.

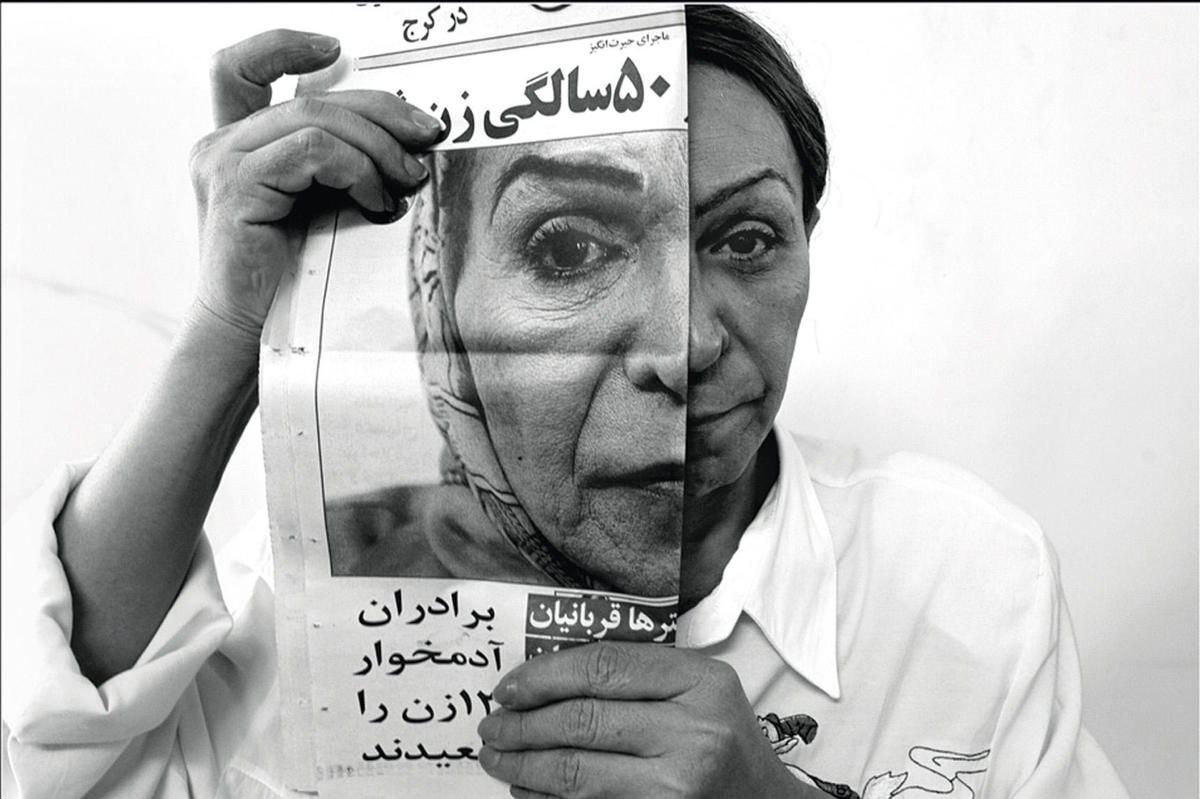

Like many a regional exhibition, 'Iran Inside Out’ was premised on commonalities, playing down artistic differences in favor of shared visual styles, cultural references, and political concerns. Beneath their surface irreverence, works like Shirin Fakhim’s superbly outré mannequins in Tehran Prostitutes probed darker national histories, such as the plight of the roughly one hundred thousand prostitutes who ply their trade on the streets of the Islamic Republic’s capital. Parastou Forouhar’s 2005 Spielmannszüge (Brass Bands), an animated loop of schematic figures playing out various torture techniques, took on a newly poignant relevance in view of post-election reports of rape and torture in Tehran’s prisons. Jinoos Taghizadeh offered timely historical evidence with Rock, Paper, Scissors (2008); the layered reproductions of back issues of Iranian newspapers reminded viewers that on the eve of the 1978 Islamic Revolution, the now ultra-conservative daily Kayhan was reporting the latest details on the “Torture and Murder of Political Prisoners.”

History repeats itself, and so does art; Taghizadeh’s newspapers were illustrated with holograms that flipped between photojournalism and details from Hieronymus Bosch. 'Iran Inside Out’ was determined to challenge neo-Orientalism and media clichés through a counter-narrative voiced by Iran’s artists, and drew on a talented lineup that ranged from modernist painters to Photoshop aesthetes. If the effect was disjunctive and contradictory, so much the better — the more chaotic and complex the impression left upon the viewer, the closer the artwork came to representing the reality of Iran’s past and present.