these women has no talent, just pretty shape, but khordadian is,,, amazing, what can i say

––dearkalem

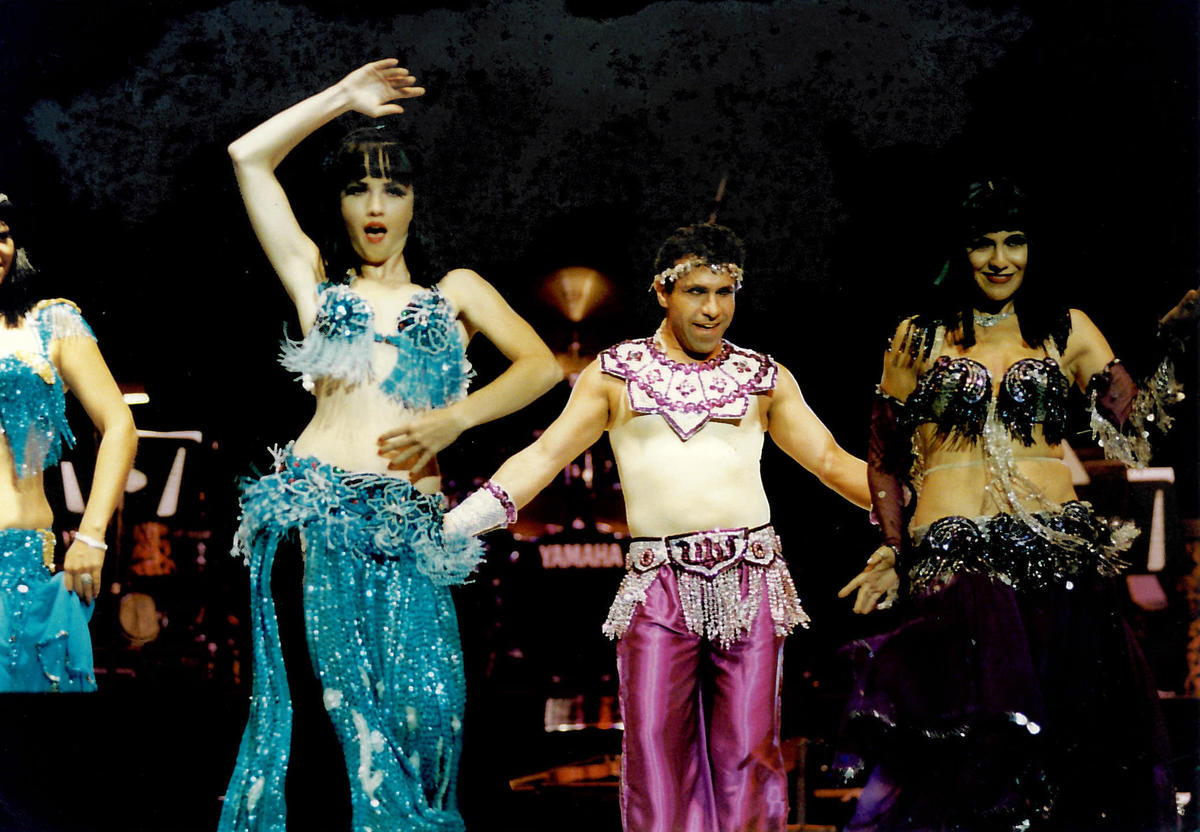

“In our culture they say men can’t dance,” says Mohammad Khordadian, a fifty-something fitness celebrity who makes his home between Los Angeles and Dubai. Since the 1980s, Khordadian has built up a dance and exercise and dance-as-exercise career that has made him the most famous Iranian mail-order entertainer on earth, beloved for his camp renditions of everything from Iranian folk dance to Arabian belly dance to American jazzercise. He has been called the King of Iranian dance. His costumes are sparkly, and come in many colors. His hips appear to be made of Jell-O.

For the past twenty-five years, Khordadian’s lispy enthusiasm has graced the Persian Satellite television stations of Los Angeles, where the Iranians of the left coast make their home. Night after night on Jaam-e-Jam, Tanin, and Iran TV, Khordadian — sometimes alone, sometimes accompanied by attractive, largely mute backup dancers — has taught Iranians and curious others to move their hips, roll their shoulders, and shimmy their hair the Khordadian Way.

Khordadian’s career took off in the early 1980s with the release of Workout and Dance Lesson #1 (viewable on YouTube as Persian Dance). It was the age of the videotape, and celebrity was in the offing for a number of exercise gurus, including Richard Simmons. Persian Dance was released by Pars Video, a San Fernando Valley–based clearinghouse for Iranian music and film — to this day, a prime source for misty royalist remembrances, avant-garde classics, and… exercise videos. In Persian Dance (today easily accessible on YouTube) Khordadian looks a bit like a muscly referee in his pin-striped workout shirt and figure-hugging Lycra. A team of three women and two men, also in extra-tight workout gear, joins him. Together, they reflect a healthy mix of people — including one woman with an almost distracting pair of buttocks. “My message is that dance is not just for perfect people,” he says. Notable, too, is “Mario,” a feathery-haired hunk whose face, shape, and demeanor cannot help but remind one of supermarket-romance model Fabio. After collectively swaying from right to left, right to left, to infectious Iranian pop for a half minute or so, Khordadian, who seems to always have one eye on Mario, announces, “With a part-i-nair, with a part-i-nair.” (He chooses Mario.) All shoulders start to shimmy, and Khordadian snaps his fingers exuberantly, Iranian-style. “It’s time to have a good time!” (He is known to mix English into his mostly Farsi monologues.)

“But don’t worry, after ten years I haven’t become American yet,” he assures us.

Persian Dance #2, Khordadian’s second workout tape, was released in 1987. He wasn’t happy with the first one, he now says. (“My hair was thinning, I had a mustache.”) For PD2, he was clean-shaven, and boasted a full head of hair, courtesy of implants. The tape made it back to Iran, where it circulated on that country’s vast black market. By 1988, most every middle-class family in Iran had a copy. Khordadian emerged as an unlikely Minister of Happiness. “It was the end of the Iran-Iraq War and all the war’s miseries. People wanted to let loose after all that sadness,” he says. The familiar yet alien choreography of Khordadian’s tapes collectively hypnotized the nation.

“I owe a lot to Jane Fonda,” he reflects. Mohammad Khordadian was born in Nezam Abad, a roughish part of South Tehran known for its fierce neighborhood rivalries and frequent knife fights. The youngest of four children, his conception was inspired by his father’s desperate desire for a second son. His mother, less inspired, did everything she could to abort him. She walked around carrying heavy blankets, ate terribly, and grew more and more depressed. She even threw herself off the roof a number of times. Nothing worked. “The baby was more persistent than her,” says Khordadian, speaking of himself in the third person. He was born February 21, 1957.

As a child, Khordadian would vie to be the center of attention, propping himself atop tables at family events and dancing until his little feet couldn’t take it anymore. His heroine was Jamileh, Iran’s first celebrity dancer. At thirteen, he joined the Boy Scouts, and it was as a Boy Scout that he made his stage debut, dressing up as a Hawaiian dancer for a visit by the Minister of Education, wriggling his straw skirt this way and that. “I liked the attention and applause I got,” he remembers. The minister, his teachers, and his fellow scouts were stunned. A star was born.

From there, Khordadian pursued dance by various means — bluffing his way into the Ramsar Youth Camp, joining a folklore troupe, dancing at the prestigious Roodaki Opera House. At the opera house he met an English woman, a ballerina named Jane, and they married. It was just about then that the Iranian Revolution began gathering force, and the couple packed up and headed for London. They danced for a while at a nightclub in Kensington called Club Iran. After a while they packed again and joined the great migration to Tehrangeles, where they split, seemingly amicably.

In May 2002, a strange headline emerged from the wire services. “Iranian Dancer Jailed for Corrupting Youth.” Another read “Iranian State Hates Fun.” Khordadian had traveled to Iran for the first time in over two decades to see his ailing father and to pay his respects after a childhood friend had passed away. Upon arriving at Tehran’s Mehrabad Airport, he was asked to report to the Ministry of Security and Intelligence, where he was instructed to keep a low profile or leave. “This country is not ready for you,” he was told. Still, he was recognized nearly everywhere he went, and people constantly asked him to dance. Who was he to refuse a crowd? When Khordadian was leaving the country weeks later, he was arrested. He spent twenty-one days in solitary confinement — the cell was so small he couldn’t fully extend his legs, he remembers — and another forty days in the notorious Evin Prison. There, Khordadian was charged with “promoting depravity and corruption among the youth” with his videos and their unabashed mixed-sex dancing — prohibited in public in the Islamic Republic. Curiously, his barely abashed homosexuality did not come up. Even at Evin, he says, the guards would trail behind him, chanting, “Mammad, we’re your fans!”

On July 7, 2002, Khordadian was convicted on all charges. His ten-year prison sentence was suspended, pending “good behavior,” but he was barred from giving dance lessons for life, even outside Iran, and banned from attending weddings and other public celebrations for three years. During the trial, one of the four judges conceded familiarity with Khordadian’s videos. “You are more talented than Michael Jackson,” the judge is said to have said. “You can dance many different styles. But can you dance salsa?”

Khordadian returned to Los Angeles to find his home in the midst of foreclosure; he hadn’t been able to pay his mortgage in months. There was great interest in his case, he says: an offer to appear on 20/20 with Barbara Walters, a book deal, and more. He refused each offer for fear the authorities would punish his family back in Iran, and his quietude provoked a variety of responses, some of them quite mean-hearted. Famed Iranian caricaturist Ebrahim Nabavi presented a sketch imagining Khordadian’s interrogation: The effeminate dancer barely understands his interrogator’s deeply masculine, Arabic-inflected Persian. At one point, he is asked about the exiled Mujaheddine e-Khalq Organization, a militant opposition group with the rare distinction of being designated “terrorists” by both Tehran and Washington. Confused, a teary-eyed Khordadian asks, “Is that a dance troupe?”

Homeless and depressed, he wandered the City of Angels. Suddenly his old haunts — the 24 Hour Fitness in West Hollywood, the kebab shops on Westwood Avenue, Cabaret Tehran — no longer felt like home.

“When I got back to LA, I felt empty. I felt I had no true friends in America. You see, after twenty-three years, I had gotten my love, which was Iran. And then I suddenly lost it.” In fact, he now admits, he had fallen in love with a person, too. “I thought he was the love of my life,” he says now. And so he did the unthinkable — or at least, incredibly inadvisable — and went back to Iran, despite everyone’s warnings.

It didn’t work out. The interrogations started all over again. So he left Iran for a third time, now to Dubai, a nearby city with its own sizable Iranian community. In Dubai, Khordadian settled into a routine, performing at nightclubs and weddings. He also opened an Iranian-themed nightclub with a cowboy motif called Cochino. (An Indian hotelier had green-lit a series of nightclubs catering to Dubai’s biggest expat communities; the other three catered to Indians, Africans, and Filipinos.) But running a nightclub was not, he decided, the life for him, and Cochino shut down in 2007.

Today Khordadian divides his time between Dubai and Los Angeles. Though he is no longer quite so limber — knee problems and a pair of slipped discs have slowed down his frenetic routine — he is if anything more famous than ever. Most of his greatest hits are watchable on YouTube, and the internet being what it is, the comments sometime descend into semi-syntactical gay- and/or Iran-bashing:

i heat this man mohammad khordadian sissy man

—TheKordistanihahahaha fagget persians!! i bet da fag king xerxes danced like dis for the spartans, in da battle of leuctra! hahahhaha no wonder leonidas didnt kill him!!

—khisraw420this guy is why Irans prez is crazy and wants to kill everyone

—mundabi

Still, most are adoring:

i dont understand the language but im all into it.. this Persian nigga gots alot of vibe

—SaulMeyers

Like Paula Abdul before him, Khordadian has parlayed his dancing into a well-paid job as a judge on a TV talent show — in his case, a German show fashioned after So You Think You Can Dance? The contestants are young Iranians raised abroad who want to pursue a career in dance. He admits, “They’re not that good.”

But Khordadian still dreams big about the future. Even now, he is preparing a theatrical play, scheduled to debut in Dubai during the Iranian New Year. The production, Ezdevaj Mashkouk (Suspicious Marriage), involves a young man who pretends he is married, with children and even a babysitter to support, in hopes of getting money from his wealthy uncle. As part of the farce, the young man, played by Khordadian, dresses up as the babysitter. One thing leads to another, of course, and the uncle unwittingly falls in love with his nephew in the form of the babysitter. You can imagine the rest. “I love Shakespeare,” Khordadian gushes.

He assures me he leads a normal life. “I’m not an artist like Googoosh or Michael Jackson. I don’t cage myself in. I live my life. I go to the gym. Sometimes I come out unshaved.”

And though his dancing career is all but over, he goes to great lengths to maintain his trim physique. “I keep my shape and my looks, and I try to update myself. I paint my hair and make it funky style, and everyone says, ‘You look like you are in your thirties!’”

Mostly, he is ready to tell the world his story. Now fifty-four, the King of Iranian Dance wants to put it all out there — his childhood in Iran, his thoughts about the revolution, the cabarets and health clubs and nightclubs in London and Los Angeles and Dubai; his videos, his stardom, his implants, and more. It’ll make for a great book — or even, he offers, a great Hollywood film. He might just be right about that.

“When Barbara Walters spoke to Ricky Martin, he wasn’t ready to come out with his story,” he says, remembering an infamous 20/20 interview in 2000, when the pop star and former member of Menudo refused to answer a series of invasive questions about his sexuality.

“But me, today, I’m ready for anything.”