New York

Yael Bartana

PS1 Contemporary Art Center

October 19, 2008–January 19, 2009

The 2001 video Trembling Time documents a two-minute pause for Israel’s war dead, as observed on a busy highway. Stretched to fill six-and-a-half minutes, the work is a slow-mo procession of cars that stop, start, and recede, from which ghostly figures emerge and stand silently.

Trembling Time was one of five videos featured in Yael Bartana’s recent show at PS1 Contemporary Art Center, organized by curator Klaus Biesenbach. Although all of these works had been exhibited internationally, this was the Israeli artist’s first solo outing in New York. The earliest of the videos included, Trembling Time introduced the central leitmotifs of the exhibition: time protracted, frustrated progress, shivers and pauses — Israel as a nation with, one might say, a “stuttering” sense of identity.

In Kings of the Hill (2003), men off-roaded their cars and trucks, maneuvering up and down dunes of sand and dirt. Others watched nearby, as if at an X Games event; a mother and daughter picnicked, unbothered by the exhaust-filled air. Although the work was understated, the machismo of the men, the tank-like vehicles, and the never-ending, slip-sliding, uphill battle — as well as the passive approval implied by the spectators — combined to form an undeniable and powerful metaphor.

The artist’s affection for slow motion and freeze frame as formal strategies was also evident in Low Relief II (2004), in which video of a demonstration had been manipulated to appear like a silvery relief. Installed on four small screens in a row, the images resembled a commemorative set of coins, the kind that celebrates a nation’s heroes — here, not just soldiers but protesters as well.

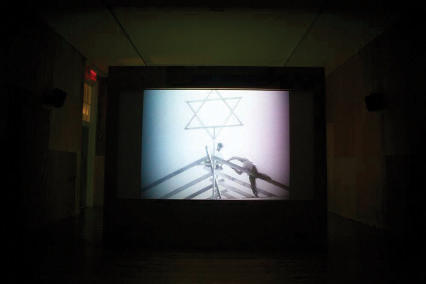

Bartana seemed to abandon her established conceptual model, however, in Summer Camp (2007), which was shown at PS1 as a double-screen projection in a large wood-paneled room. One side showed the artist’s edited, twelve-minute version of Awodah (1935), a Zionist propaganda film. It began with a man walking over rocky land, searching for a suitable spot to build, and ended with the construction of a village. On the other screen was projected Bartana’s 2007 video of members of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD) rebuilding the home of a Palestinian in the West Bank, which had been demolished by Israeli authorities. (This installation of Summer Camp was much stronger than its presentation at Documenta 12 in 2007, where Awodah was not included.)

Similarly structured, the two videos synced at times — in sound and image — such as when both showed a hammer pounding nails into a wooden beam. But the ICAHD video was primarily oppositional. While Awodah was in high-contrast black and white, with romantic shots of laboring bodies — a 1930s specialty — Bartana resisted aestheticization in her own color video. In the propaganda film, although a few Arabs could be seen (with goats and camels), the landscape appeared unbuilt; in the 2007 work, the plot of land was undeveloped because the Israeli state had destroyed it.

Summer Camp thus countered the Zionist mythology that led to the founding of the state of Israel, and the ideology that continues to underlie its relations with the Palestinians. There was nothing hesitant about the action onscreen, which, although workmanlike rather than triumphant as in Awodah, progressed forward to the resolution of a rebuilt home, constructed by Israelis and Palestinians together. The stutter was gone. But then, a final image: an Israeli police car drove by, silent as the hawk that earlier flew through the sun-bleached sky. As the looped videos repeated, so did the cycle of occupation and destruction.