At St Joseph’s Boys’ High School in Bangalore, where I was a student in the late 1990s, the Tamil Brahmins ate curd rice in small groups, eschewed sports, dressed neatly, and raised their hands milliseconds faster than anyone else. They were also, it should be said, easy to bully. They would often sit in the second bench, respectfully close to the teacher, who loved them more than his own children. At least, that’s how we rowdier castes felt.

In his essay, “The Best Second-Rate Men in the World,” an investigation of the “ideal type” of the Tamil Brahmin, the journalist N. S. Jagannathan asserts that the “central characteristic” of a Tamil Brahmin is an “instinctive preference for anonymous functionality behind the scene,” an aversion to risk, and a fear of being singled out. Under the British, the Brahmins of southern India acquired a near monopoly on jobs in education and the civil service, engendering resentment among their British overlords and the lower castes. In the twentieth century, a succession of political parties organized against Brahmin control, changing the balance of power by setting aside positions for other castes in schools and the public sector. When the tables turned, the Tamil Brahmins left for greener pastures rather than put up a fight. Today the majority of Tamil Brahmins live outside Tamil Nadu, their home province. Some relocated to different parts of India, while countless others decamped to Europe and North America. Today most Tamil Brahmins in India have family members abroad; many live in the United States and work in the information technology field. If you are reading this in the US, you’ve probably met one, and you probably don’t know it.

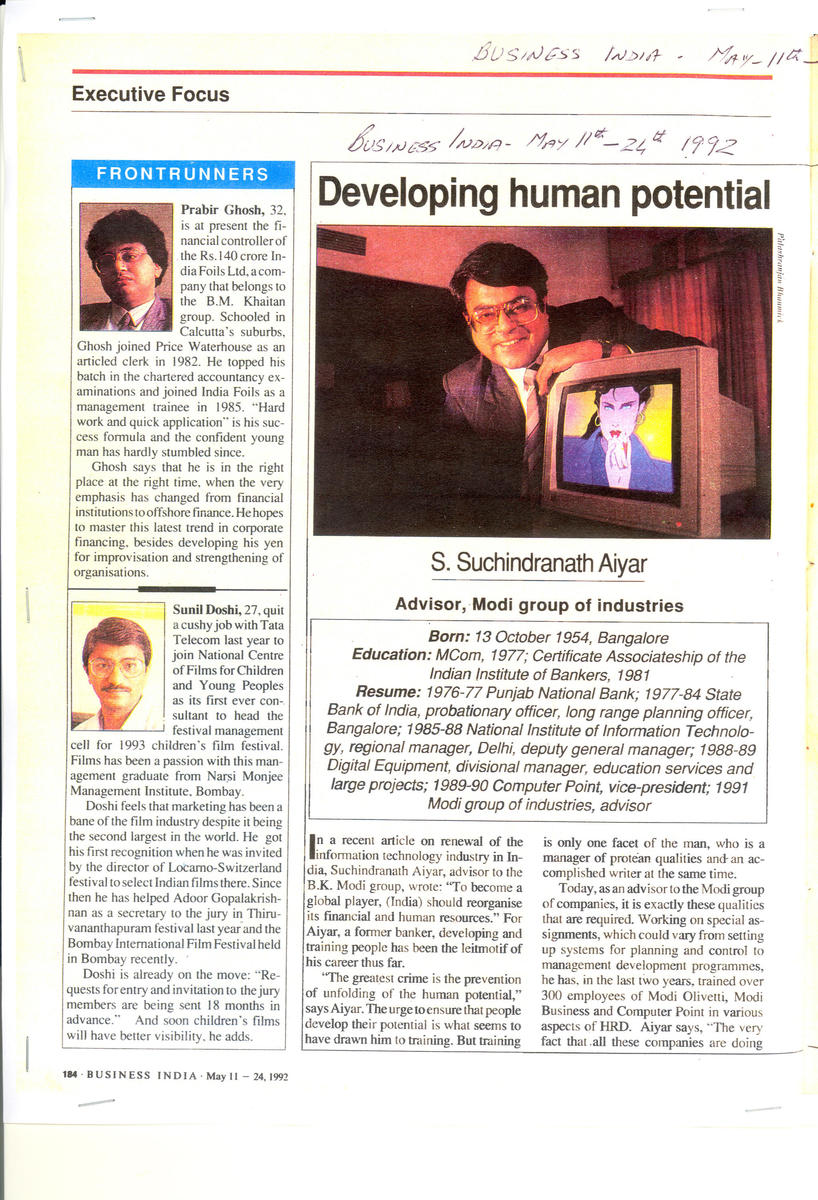

Suchindvath Aiyer is a bit of an anomaly. Although his career bespeaks an exemplary Tam-Brahm pedigree — he has worked as a civil servant, an IT manager, a management consultant, and the president of the East African Internet Association — the fifty-two-year-old is outspoken, pugnacious even, and a loud and tireless opponent of injustice, especially against Tamil Brahmins. “He will say things most others are too scared to say,” I was warned. “No one will publish your article.” He has a reputation for verbally assaulting the denizens of Koshy’s, the café that epitomizes old Bangalore, and has taken the Bangalore Club Committee to court for defamation of character. He often pens caustic letters to local newspapers, deploring the many travesties of contemporary Indian politics. And yet he is warm, quick with a smile or a self-deprecating comment, even as he shares his apocalyptic hope that the Naxalites will destroy India, ushering in a new beginning.

Aiyer lives in a third-floor Bangalore apartment with a fortified door that’s emblazoned with a rooster and the words “From Darkness to Life.” (The family crest, he later reveals.) Upon arriving, I remove my shoes and walk down a corridor lined with Stetson hats and photographs of lions looming over dead zebras. The living room has a wooden shelf stretching from one end to the other, lined with college trophies for debate, elocution, and quizzing, along with a Japanese sword, a savage-looking spear, and a crutch. Aiyer limps badly, the aftereffects of two disastrous automobile accidents, but his back is erect.

Ryan Lobo: What is the story behind the spear, if you don’t mind my asking?

Suchindranath Aiyer: I was in Africa for five years. I had been working as a management consultant in Bangalore when I was invited to interview for a job in Nairobi. I went to enjoy the wildlife and I fell in love with the place.

I had my first accident in Kenya, actually, on the Mombasa-Nairobi highway. We had a cliff on one side and an abyss on the other, so I had to drive head-on into a huge sixteen-wheel truck or my three passengers and I would have been killed. That took something, but I did it. Later the doctors told me that I had braced myself too hard and had absorbed the whole shock of the impact with my hip, which then shattered. If I only had relaxed, I would not have been injured.

Like this. [Picks up spear and sets the base on the floor, with his foot on top, his body bent.] This is how a Masai warrior would hold the spear against a charging lion. Once upon a time, an uninitiated Masai would have to kill a lion with such a spear to become a man. The old Masai men are, in their philosophy, very similar to Brahmins and the covenant of Brahma, you know.

RL: This notion of being Brahmin seems very important to you.

SA: I have been brought up very deeply with this. The life of the Brahmin is the quest for the immortal in oneself. It’s not just a caste. It’s a value system and we are losing it in this banana republic.

All Brahmins are descendants of seven sages who lived thousands of years ago. These sages received a covenant from Brahma, the creator, and he gave them the purpose of man, which is to build a paradise on earth based on the pillars of truth, virtue, and beauty, set within the ambit of divine law, charity, mercy, and moderation. Whosoever takes a step toward this goal will derive indescribable joy, and anyone who steps away will suffer enormously. This is the covenant of Brahma. It governs my life and is what makes me a Brahmin.

RL: You speak of this with pride and even tenderness. Where does your faith come from? The idea of the Brahmin isn’t very respected today in India.

SA: The community is persecuted now. It wasn’t always this way. The Brahmins had a love-hate relationship with the British. Don’t forget, it was the Brahmins who the started the revolt against the British in 1857.

We made good clerks for the empire as we had discipline and learning and language skills. At the same time, the British had a suspicion about us, which became a veiled anger. Strange as it may seem, we served them well. My paternal grandfather was an engineer whose work saved much of the Cauvery riparian areas from flooding, and the British gave him a title. The British were far more fair than the rascals who rule us today.

RL: So when did the discrimination against Brahmins truly begin? And why have they left in such large numbers from Tamil Nadu?

SA: In 1938 the British brought out a discrimination law called the Communal Gazetted Order to exclude Brahmins from promotion and employment whenever possible. The British were wooing the anti-Brahmin Justice Party. They also supported the expropriation of Brahmin land. The pogrom began in the south of India and it’s still going on today.

You are an orphan if you are a Brahmin, especially in Tamil Nadu, one of our original homelands, because of the political parties that make scapegoats out of us for their political ends. We form the diaspora now, all over the world and in Bangalore as well. We are like the Jews in this way, fleeing our homeland, but we shall survive.

RL: What’s your understanding of the caste system? Who are you within this tapestry of caste?

SA: The caste system has four main castes, Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (merchants), and Sudras (workers). The word Arya means several things. By connotation in India, it means noble. My surname comes from Arya. In the south, the suffix rr was added out of respect, and Arya became Aiyer, or Iyer, over time.

My first name comes from a place called Suchindran, near the southern tip of India. You can call it legend, but the chronicles say that we came to what is now India from what is now Afghanistan, just before the Mahabharata War. The hero Janamejaya had destroyed all the snakes in the world to avenge his father’s death by snakebite, but he was cursed for this action. To escape the curse, he came south to Suchindran.

This is who I am. And this story has been passed down for close to five thousand years from Rig Vedic times, from mouth to ear, father to son, priest to child. This story has passed down through families, in good times and bad, through war and famine, genocide and peace. This knowledge about ourselves in the universe has sustained so many during dark ages, so many times. Even now.

RL: Would you say the old ways were better than what we have now?

SA: Absolutely. Look at what we live in now. Corruption. Bandicoots. We could abolish the income tax for the next century if we got back what these politicians have stolen from us. Billions. Have your seen the newspaper today? The state-run Life Insurance Corporation of India is spending money on buffets to entice their employees to come to work.

In ancient times, the temple was the place of last resort. When invaders came, or disaster struck, people would flee to the temples. The temple was like a bank; its money was to be spent only in the case of catastrophe. There are no last resorts now. The government has been stealing the offerings at the Tirupati temple for ages. Did you read the papers yesterday? They have stolen millions.

Today the Brahmin has neither power nor wealth, so why would anyone want to emulate him? Why uphold order, law, or integrity? All anyone needs to do is see a Brahmin and know that that those values lead to poverty and worse. There is no last resort.

RL: What is your last resort?

SA: My foundation from childhood, the rituals I was taught. The meditations I do. I meditate for two hours every day and commune with my spiritual teacher. This act of watching oneself, this comfort that is within, is the last resort.

RL: Shouldn’t this idea of Hinduism that you have — the inward observance and the covenant of Brahma — help unite Hindus across India, rather than separate them?

SA: There’s no such thing as Hinduism. It’s an agglomeration of religions. The Aryans came in and their law was imposed on a host of religions. That’s why it’s called a polytheistic religion. We Aryans have the sun as the living idol and we believe in Brahma. After independence the pyramid has been turned upside down. We have made sure the thugs and bandits are at the top and the intellectuals and the thinkers are at the bottom. We have ensured that people without philosophy and without culture are at the top, at the cost of people with integrity.

RL: Why don’t Brahmins fight back, then?

SA: We are separate from this idea of India that you have. We never felt it necessary to waste our lives fighting. We can do whatever is required on the material plane, of course, but our main calling is divine law and justice. In any case, historically speaking, we prefer to leave and start again.

Most of my family is in the United States. Unfortunately my parents brought me up to be patriotic. By the time I was enlightened, it was too late. One of my nephews is a neurosurgeon and the other is a radiologist. In India they would not have been admitted to medical college, as they are Brahmins. My daughter is in Germany doing a PhD in robotics. She scored ninety-nine percent on her entrance exam and still didn’t get admitted to medical college in India because of reservations for lower castes. I have told her never to come back.

RL: There seems to be a lot of hurt in what you say.

SA: It’s not just hurt, it’s hatred. Suppressed Brahmins here keep their mouths shut — you have the Indian state, cops, goons, and others against you. I don’t keep shut, but most Brahmins are family people. I don’t keep shut because the laws in India have screwed me so much that I don’t care. I don’t care! But at the first opportunity, I will jump ship. This country has no allegiance from any Brahmin. The Indian government rubs the patriotism out of you. America is the new promised land. They reward hard work, integrity, and diligence — all Brahminical characteristics.

RL: A stereotypical view about Brahmins is that they look for stability over money and ambition. Is that true?

SA: Some of us are introverted. But we are used to adapting and finding the best of Brahmin philosophy elsewhere. I have had fabulous communion in the most unlikely of places.

RL: You spent time in Japan, correct?

SA: I belong to a Japanese spiritual organization called Toho no Hikari. Light from the East. They’re into three activities — spiritual healing, nature farming, and the promotion of the arts. Their founder, Mokichi Okada [1882–1955], was and is my guru to this day. That painting on the wall is by him.

RL: What was it that attracted you to Toho no Hikari?

SA: These people do exactly what the covenant of Brahma expects. They are the only organization I have found that pursues the covenant of Brahma. They had an office at Richmond Circle in Bangalore in 1995, however they fled India with great suspicion — they were cheated here. I followed them to Japan in 2002 to persuade them to return.

RL: What happened?

SA: I failed. In Japan I had a second accident — a bus I was in went off the road. My left shoulder and right leg were crushed. I took the bus company to court — as a foreigner, I was to receive less compensation than a Japanese person. During the two and half years of the proceedings, Toho no Hikari looked after me as a mother would look after a child. So did the Tamil Brahmin community in Japan. They would bring me idlis and sambhar to eat in the hospital.

RL: Did you win the case?

SA: No. The Japanese Supreme Court ruled that a Japanese life is more valuable. I was deeply disappointed. In court cases, no matter how right you might be, laws take their own course. You cannot go to courts expecting justice. I should have learned that in India. But I was given a chance to fight and seek justice, and for that, I am very happy.

RL: Where else have you found this sense of community?

SA: I went to London in 1987. It was the first time I have ever felt at home. I never felt at home in India except for my early childhood, with my grandparents. They ran a very Brahminical household — cleanliness, orderliness, and rule of law were the norm. When I got back to India, I realized that I didn’t lose my temper the whole time that I was in the UK.

RL: So culture shock happened when you returned to India rather than when you were abroad?

SA: There was a Bombay cop at the immigration line going around and tapping everyone on the shoulder with his cane. I barked at him and the cop called his superior who left when he saw me standing there, dressed in a suit. He personified what India was to me — all that stinks, all that is unholy. This is what the political leadership of India represents to me. After experiencing hygiene, order, and rule of law abroad, I returned to find that most Indians lack hygiene, manners, and etiquette.

RL: You seem very self-aware. Have you ever considered unlearning some of these qualities that might cause you to lose your temper?

SA: A huge superstructure is built on these critical incidents. I would lose a lot of things about myself if I tried to change. I love my hatred of injustice — I don’t want to lose it. So it’s more a question of accepting myself now.

Ryan, you must emigrate. I am too old; you are still young enough. New Zealand is a good choice. Japan if you have the language — they are hyper-tolerant of eccentricity, but your freedom ends where their nose begins. Switzerland is like Singapore — intolerant — so don’t go there. In New Zealand you get elbow space and they speak English, of a sort.