At night on the Thames, skippers of elderly tugboats tell horrified and delighted deckhands about the headless torsos of African girls found washed up on the shore downriver the previous week. They talk about the illegal immigrants who try to steal into the country by water: Lithuanians and Ghanaians and Iraqi Kurds who are squeezed by traffickers into near-airless tin containers welded to the bottoms of foreign ships. The containers, and the corpses inside, are only discovered when the ships harbor at dry dock. “Poor bastards,” sigh the bargers.

Careless talk costs lives. London is the CCTV capital of the world. The fear of shoebombers, nonnative intellectuals with attitude, and disaffected prole boys eager for a ballistic shortcut to redemption means that the city is being monitored as never before. Mosques are swarming with informers and undercover police. Savvy keystroke cops comb backstreet cyber-shacks and internet cafes, checking to see if the migrant kids who spend their evenings trawling for ethnic porn are also visiting terrorist sites. The shelves of religious bookstores are scoured by security officers looking for inflammatory pamphlets or cassettes castigating the immorality of the West.

Communication, under these conditions, goes into retreat, moves sideways. It occupies different spaces. A clutch of Fujian waiters, none of them in possession of working papers, huddle around the kitchen table at the back of the Soho restaurant where they labor fourteen hours a day for $200 a week, chatting and gambling before they catch the night bus home to the one-room flats they share with three other people from their village. A dead-eyed slumber of stubbly private-cab drivers sit in a smoky Notting Hill basement room, swapping insights about which routes not to take, one of them telling an only slightly embellished tale about the sexual come-on he received earlier that evening from a pretty girl. It turned out (“What a surprise!” laugh the others) that she didn’t have enough money for her fare.

Subterranean stories: the flushers who wade through rivers of tampons, rats, and fatty quicksand, to keep the city’s sewers functioning, like nothing better than to laugh. They’ll cackle as a hungry gang member finds an orange amid the filth and promptly starts eating it. Or at the desperate worker who loosens his uniform and has a dump in a corner. Life in the sewers is hard, and humor — the coarser and blacker the better — raises flagging spirits. One flusher bought his wife a bouquet of flowers on their wedding anniversary. “I suppose you’ll be expecting me to open my legs for you,” she remarked. “A vase will do,” he replied. Another remembers the night he emerged from a sewer at Leicester Square, dripping grime and shit, only to find a young female tourist peering at him. He held out his hand: “Smell that. That’s Canal N˚5, that is.”

Aerial stories: many of the cleaners who polish and shine the top floors of the corporate towers in London’s Docklands business district don’t exist. Employed by violently penny-pinching sub-sub-contractors, they’re illegal migrants whose names are not to be found on any official ledgers. They have no recourse to the law if their salaries are randomly docked, or if they get hurt because of shoddy safety equipment, or if they’re sexually harassed. So they keep their heads down, their lips tightly shut.

They notice things, though. That the CEO earns £2680 an hour, while they earn a mere £5. They bridle and chafe. In their minds they’re somewhere else. Sometimes, as dawn is rising, the cleaners take a break from crumb-picking and mousetrap-shifting. Their night’s work is almost over. The offices are as clean as the hills and golf courses of the foreign kingdoms to which they dream of migrating. They stand up tall, proud of the reformations they have wrought. Just for a minute or two, they allow themselves the luxury of imagining that they are the shirt-tucked, chauffeur-driven masters of the universe, lording it over the snooty pen-pushers and keyboard-dabbers whose garbage they have spent the last seven hours collecting. “Clear out your desks and leave!” they fantasize declaring.

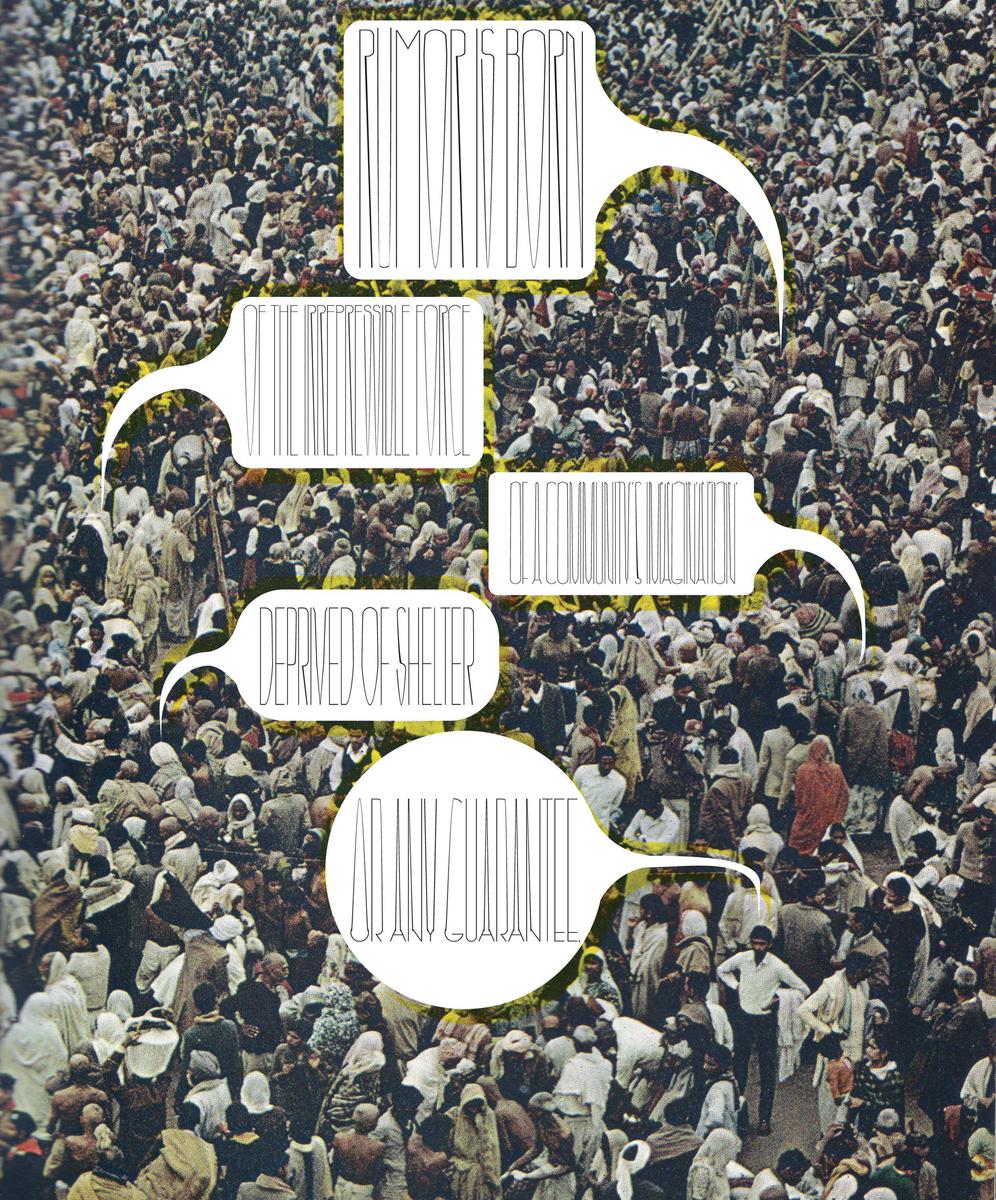

In an introduction to Berji kristen (1984), Latife Tekin’s novel about the slum and squatter towns found in Istanbul, John Berger wrote, “Rumor is born of the irrepressible force of a community’s imagination deprived of shelter or any guarantee.” But rumor also helps, in however piecemeal and fractured a fashion, to create the possibility of community. The exaggerations, gags, and proverbs make up a ragged, multi-authored narrative from which is forged a raw and temporary nation for those people who cannot locate themselves in the grand narratives and lofty language of the state.

Beneath London, in badly heated areas marked “No Entry,” rooms little bigger than broom cupboards, are found Polish and Nigerian and Italian and Jamaican subway cleaners. They speak heavily inflected English, an undercommons Esperanto. They plot unionization campaigns. They exchange examples of bad management practice. They participate in underground information networks, many of them comprised of gossip masquerading as fact, about fresh passport scams, family-benefit concessions the government has introduced, new contracting firms that offer cleaning recruits an extra week’s holiday each year. For these new and lonely Londoners, rumor is a lifeline, a passport to a happier time and place.