Figure lying on floor of mosque, surrounded by standing soldiers. Hooded figure on box, wires trailing from fingers. Figure on a leash with soldier. Green-hued landscape crisscrossed with moving lights. Aqua-tinted aerial view of anonymous city intersected by moving lines of light. There is an abstract and uncanny quality to many of the images of violence in Iraq that are circulating today. These images distinguish themselves from the more familiar humanist portraits of life under occupation in that they don’t come with reliable instructions. One is never sure how to really look at them. Perhaps that is their power. Of the abstract images, there are two types. One is characterized by distance and abstraction. In the other, all sense of distance is erased. How are these two types of image related?

In a critical studies course I taught at New York University a few years ago, I showed my students nineteenth and twentieth century American photographs of lynchings. The photos had circulated first as postcards, later as a traveling exhibition, and then as a coffee table book. Wanting to avoid a discussion about white guilt, I challenged my students to respond to the images formally, as images. If this were a Francis Bacon painting, how would you describe it? What does it do and how does it do it? Describe for me the relationship between the background and the figure. It was a difficult exercise for us all. One image was particularly disturbing. In it, a crowd had gathered around the smoldering remains of a male figure. The white boys were staring directly back at the camera. Have you ever looked for too long into someone’s eyes? There was an uncomfortable intimacy that was established in that gaze across historical time. Where is this moment located in the development of humanist perspective? Is this the birth of the subject? What exactly occupies those figures left standing? It’s obscene, one student remarked, because it gives the appearance that what is happening is happening every day.

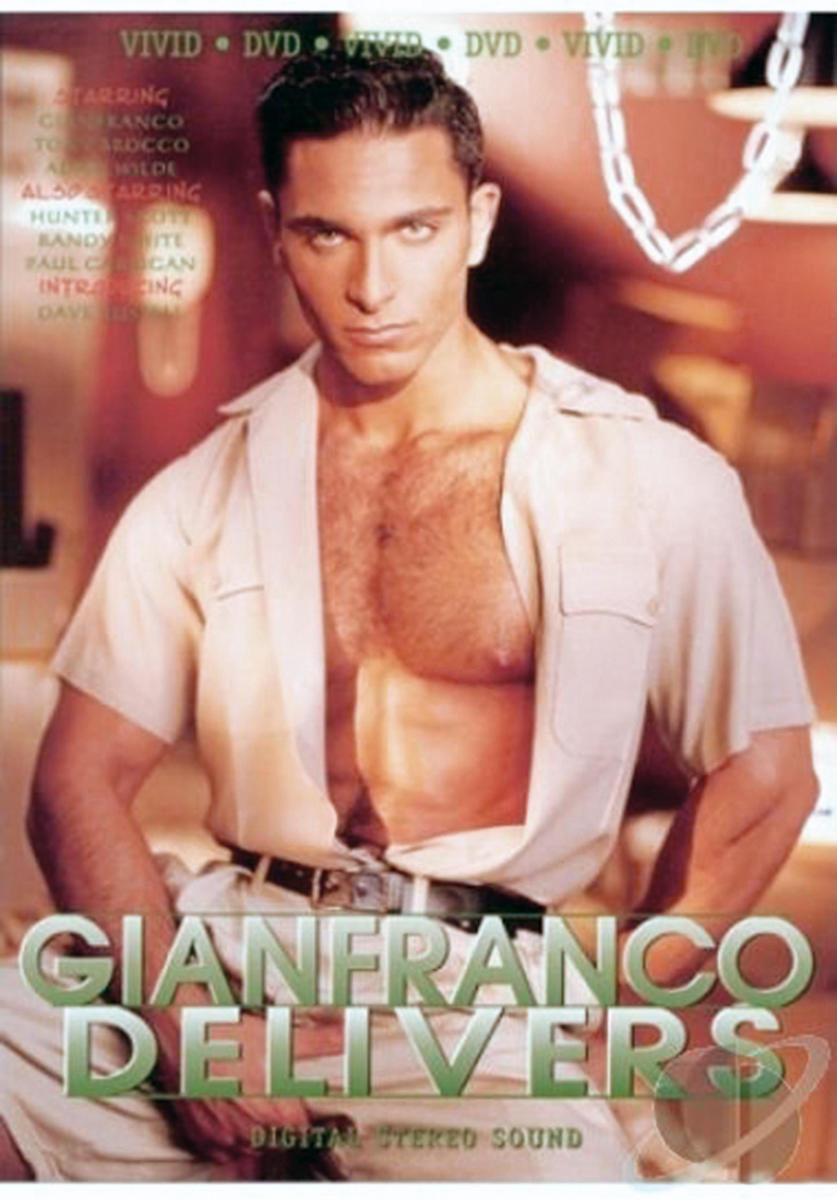

By all accounts Ali was a difficult person to work with. “I spent a week in Palm Springs with him,” comments co-star Jackson Phillips. “He was so difficult to work with that in the middle of our scene I slapped him as hard as I could across the ass. He jumped five feet. The crew and director — ChiChi LaRue — applauded me.” When he entered the adult film business in the late ’80s, Ali took a marketable name. First it was Johnny Diamond but then, trading on his “Mediterranean” looks, he changed it to Gianfranco. It’s not clear whether he chose the name for himself or whether his agents, Con Merten or David Forest did. He went on to star in all-male adult movies like Leathermen and Pleasing Young Men and Erotikus and Gianfranco Delivers. Phillips commented, “He was focused on becoming famous. He seemed to believe that if he told the gay press he was straight, it would benefit his career. Shortly after we filmed he began a serious campaign to get physically bigger. I would not rush back to work with him again.” It’s not clear whether Gianfranco was of mixed Iranian and Italian parentage or if both parents were Iranian, but Forest comments that Gianfranco was “100% homo.” Whatever that means. He appears to have been selective about the sex acts that he engaged in on camera. Perhaps that is what made him so difficult.

He left porn in the Nineties and resurfaced as an escort. Images of him at the time show a more bulked-up, shaved-down version of his porn persona. Later he would advertise as a masseur in Los Angeles under the name of Ali. It’s been said that he attended chiropractic school and now has his own practice in West Hollywood. Doctor Ali. There are competing fragments about Ali floating around on and offline. If I were to narrate them into a believable story, it might go something like this: the child of Iranian émigrés grows up in California and is conflicted about his identity; he is 5’7”, swarthy, and different from his sun-bleached peers; as a young adult, he learns to pass for a more acceptable form of Mediterranean; later, he matures into a new sense of self-awareness, quits porn and goes to school to prepare for a more sustainable livelihood; sometime during this period, he finds comfort in Islam, attends a local Los Angeles mosque from time to time and keeps an image of his imam in his bedroom.

Spread across 280 acres, Abu Ghraib is the largest prison in Iraq. At times it held more than 10,000 prisoners (although some estimates account for 20,000). Built under British supervision and American design in the 1960s, the prison is modeled on the 19th century linear example of Auburn Prison in upstate New York. Cell blocks run perpendicular to a central corridor. The seventh cell block is where most of the torture took place. It is an uninterrupted hallway of 103 cells, each measuring 6 x 10 feet. It can only be monitored by guards on foot, thus providing intermittent supervision.

Every society produces its own space. Industrializing society produced the modern prison type. In the nineteenth century, prison became the general form of punishment, replacing torture. The body no longer needed to be marked. In prison the body was restrained, its time measured out and fully used, its forces applied continuously to hard labor. Michel Foucault has pointed out that the prison form of penalty corresponds to the wage form of labor. A new optics also came into play. Drawing on Jeremy Bentham’s ideas of the Panopticon, this new way of seeing demanded that everything be observed and transmitted. With this new way of seeing came a new mechanics of isolating and regrouping individuals and a new physiology of standards that define the criminal class and its inverse, the bourgeoisie. Historically produced, space both shapes and is itself shaped by social practice. Spatial structures like the prison don’t just reflect political and social practices. They shape the spaces in which social life takes place and condition those practices. Architecture forms habits in its users by engaging them in a state of distraction. The typology of the modern prison was instrumental in the development of the psychology of the subject.

In the military, homophobia coexists with latent homosexuality. This suppression of desire is the foundation for military cohesion and soldierly bonding. There is a flourishing underground economy of all-male pornographic videos of American soldiers, many of whom have returned from or are about to embark on tours of Iraq. They are part of the same industry of videos of misbehaving frat boys, co-eds gone wild on spring break, suburban swingers taping their trysts. Slavoj Zizek has written that the Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib were being initiated into American culture: they were getting a taste of the obscenity that counterpoints the public values of personal dignity, democracy and freedom. Donald Rumsfeld has already promised that there are stronger images to come, suggesting that the photographs were merely a coming attraction to a more exciting main feature.

To paraphrase Guy Debord, pornography is not just a collection of images; it is a relationship between people that is mediated by images.

Walking across campus at night I am struck by the sheer number of students who traverse the quads speaking on their mobile phones. They move with little acknowledgement of the other students, also on mobile phones, who cross their paths. It is almost as if they are not there. Or the campus is not there. It has disappeared into the 0s and 1s that define our current reality. We can be there without being there.

On film, Gianfranco was never penetrated without a condom. Did he insist on only engaging in safe sex? The desire to be safe often contradicts the desire for experience. This is a moment in which safety has far outstripped experience. We can have coffee without caffeine, beer without alcohol, sex without touching, and war without casualties. I am assured that flying is completely safe before I step on the plane and plug myself into the entertainment console on the back of the seat in front of me. At the end of the process of virtualization we begin to experience reality itself as a representation. We are daily immersed in the reality of space-defining forms but another level of our psyche resists that immersion. Extreme violence erupts in the spaces that are stripped of reality’s deceptive layers.

“A space must be maintained or desire ends,” writes Anne Carson in Eros the Bittersweet. To fill that space would be annihilating but we try to fill it nonetheless. In loving you I found something inside you that I needed to destroy much more. The woman holding the leash, the soldiers standing over the fallen figure, the crowd gathered around the burning body, the rockets lighting up the color field, Gianfranco on his back with his legs up in the air: these images are the evidence that everything we want can’t really be touched. They are the state of tension on which we’ve built the fragile universe.