Do you know about frog tongues? They’re among the softest biological materials known to science, as well as the stickiest. This is partly due to the unusual qualities of frog saliva; like ketchup, toothpaste, quicksand, and blood, frog spit is a non-Newtonian fluid, by turns liquid and solid, prone to harden on impact. Frog tongues are also fantastically strong, even as they are characterized by what one writer called their “superlative softness.”

Last November, Emmanuel Macron, France’s smooth-faced, soft-spoken president, made a startling announcement during a visit to the United Arab Emirates. “Abu Dhabi,” he said, “has become the capital of art, architecture, and mankind’s heritage.” He was, no doubt, flattering his hosts. Under Macron’s leadership, France has leapfrogged to the top of the Soft Power 30, a leading index of international influence; the award cited the country’s cuisine, its “unrivaled diplomatic network,” and its “cultural assets,” as well as the un-Trumply charms of its youthful president. But Macron was also, in a sense flattering himself. Macron was here for the opening of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the first overseas franchise of the Louvre museum, whose Paris original is the world’s preeminent art-pilgrimage site, home to arguably the world’s most famous painting (and definitely its best-known iteration of side-eye), Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

For a thirty-year lease on the name, fifteen years of curatorial expertise, and ten years of loaned artworks, the UAE will end up paying on the order of 1.25 billion dollars. Sweet talk, on the other hand, is cheap. Addressing an audience that included Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, Abu Dhabi’s Crown Prince, as well as Dubai’s ruler, Sheikh Mohammed, Macron waxed grandiloquent on the struggle to “defend beauty, universality, creativity, reason, and fraternity,” in which France and the UAE were now comrades-in-arms.

This was just the sort of ad copy the government has always craved. Capital of art, architecture, and mankind’s heritage has a resoundingly superlative ring to it, and the UAE is a nation obsessed with superlatives. Growing up in Dubai, I became accustomed to our limitless hunger to be the most whatever. We built the world’s tallest building and the world’s largest shopping mall; produced the world’s longest painting (6.74 miles) and the world’s largest human waving flag (4,130 people); removed the world’s largest kidney (9.25 pounds); and so on. It’s like the flurry of “Firsts!” in a comment section, except that the comment section is the Guinness Book of World Records. Why shouldn’t we have the softest soft power, too?

I’ve long admired the varieties of herbal Viagra on display at my local bodega: XXLant Gold 5000, Power MAX Revolution, or (my favorite) Ultra HurricaneX 2000 “Super Power Mysterious Formula.” The gradients and shiny, beveled shadow effects all contribute to their wonderful go-faster feel, like a horse on a treadmill. If the UAE was a petrol pump — roll with me here — Dubai would be the high-octane Ultra HurricaneX 2000 premium version, Sharjah would be diesel, and Abu Dhabi… I guess Abu Dhabi would just be regular? At risk of broad strokes, we might characterize Dubai’s art scene as being primarily commercial, defined by its glitzy art fair, its galleries, and its first-in-class duty-free offshore storage facilities. Sharjah, meanwhile, is known for its long-term commitment to arts infrastructure through the activities of the Sharjah Art Foundation, its biennial, and its sister museums. Sharjah presents as organic, authentic, unthreatening; its arts areas are even somewhat pedestrian-friendly. (People love the idea of walking outside.) You can become fond of Sharjah in a way that Dubai will never let you.

Abu Dhabi’s strategy has been very much one of importing famous brands and hiring brand-name architects to design them. Jean Nouvel’s Louvre is but one of many; the controversial Saadiyat Island project features an array of luxury villas, hotels, and a campus of New York University, as well as the gilded toilet rolls of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim and the Zayed National Museum, designed by Norman Foster to evoke a spread of falcon wings. This last is a collaboration with the British Museum, or it was; recent reports suggest that the agreement has been terminated early due to construction delays. Like many of the bolder plans to turn Saadiyat into a cultural oasis, the National Museum was originally scheduled to open years ago. Its future status, like that of the Guggenheim, remains opaque. For the foreseeable future, the Louvre is Saadiyat’s one-and-only main attraction.

One Wednesday in December, I made the trip down to Abu Dhabi — about seventy minutes by car — to see the new Louvre for myself. I’d skipped the press opening in November, looking forward to seeing it at leisure, without the madding crowd. That was my first mistake; the second, arriving on a scant few hours of sleep. Really, I just wanted a chance to deploy the phrase “Eat, Pray, Louvre,” and fittingly, the first thing I did was eat — a dubiously named “Hummus Addicts” sandwich, which would turn out to be the highlight of my visit. In a notable missed opportunity, neither éclair nor mille-feuille nor macaron was on the menu, let alone frog legs. Before my visit, I’d been thinking about that scene in Godard’s Bande à part (later reprised in Bertolucci’s The Dreamers) where the protagonists race through the halls of the Parisian Louvre. There was zero chance of that here. These halls were heaving with visitors — primarily European tourists, from what I could overhear at the cafe, with a smattering of local, mostly South Asian, families. (At AED 60 for an adult, entry is neither steep nor particularly affordable; press, students, and children receive discounts.) Aggressive lighting and a curious preponderance of plate glass further contributed to the Harrods-Food-Hall-during-the-Christmas-crush vibe — the most Emirati thing about the whole affair.

Pray? I’m not a religious sort but the building is unabashedly stunning, a series of spaces so subtly lovely so as to suggest the sublime. The last stretch of the drive down to Saadiyat Island from Dubai is particularly scenic, as the highway peels off and you pass over a series of islands surrounded by crystal-clear water and surprisingly lush mangroves. The museum architecture seamlessly extends this effect. What appears from some distance as a low dome half-submerged in the sea reveals itself as a soaring filigreed canopy set among modest low buildings. Inside, it’s a masterclass in shifting light and shade. It is said to be inspired by the dappling of light under a palm tree, but the amphibious canopy reminded me personally of the exquisitely horrifying backside of the Surinam toad — a pockmarked landscape through which mama toads absorb their own fertilized eggs, and from whence baby toads wriggle out when the stars are right. The museum is wholly open to the sea, an effect only slightly marred by the checkpoint-like entrance. Then again, the building — the Louvre Shack, if you will — was always going to be beautiful.

Look, it is what it is — an industry-standard world-class cultural institution, just like the Abu Dhabi Tourism and Development Investment Company (TDIC) ordered. The reviews have been mostly positive — Holland Cotter in the New York Times called it an “Arabic-Galactic wonder” that “revises art history” (tempered with the requisite tua culpas about the migrant labor that built it, because how else can you talk about the Gulf?), while the V&A’s Tristram Hunt, writing in the Guardian, sounded downright envious: The new Louvre “is a template for the mix of ingenuity, vision, and spirit of collaboration which post-Brexit Britain will need to display on the world stage.” In any case, the Louvre is an unabashed success on the vernacular criticism front: 656 Tripadvisor reviews in, it’s already ranked #11 (and rising) out of 153 things to do in Abu Dhabi, with an average rating of 4.5 stars. (#1 is the Sheikh Zayed Mosque; Bidoun recommends #4, the Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital.) The handful of negative reviews decry congestion and crowd management, staff arrogance, and the absence of the museum’s most publicized (and, at $450 million, priciest) acquisition, da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, a portrait of an extremely chill Jesus Christ that won’t go on view until April. Travelers mention “Van Gogh” (7 reviews), “amazing roof” (5 reviews), and “pieces of art” (5 reviews). As a flexy contrapposto of soft power, TDIC’s gambit seems to have paid off.

Mind you, there’s undeniable value in the sheer access that an institution like the new Louvre affords, especially for those who might not have the funds or visa-related mobility to see such works in their European (overwhelmingly French) resting places. Should it ever be completed, the Guggenheim will do something similar for contemporary art. Education seems to be a priority. The museum makes thoughtful use of audiovisual and interactive elements throughout; technology is embedded in a way that feels surprisingly natural, and not hastily jugaaded on. I appreciated the accessible rigor of its inaugural temporary exhibition, ‘From One Louvre to Another,’ though I found it a little snoozy and its Enlightenment revivalism politics rather grating. (Someone more interested in the Louvre’s French Revolutionary origin story and/or gilded maximalist interiors will probably fare better.)

There’s a wealth of art, some of it from the museum’s small but growing permanent collection but mostly drawn from the consortium of French arts institutions party to this particular fête, including the Louvre, the Centre Pompidou, and the Musée d’Orsay. Lately I’ve been doing online jigsaw puzzles as a way of working through an art history I never formally learned — I like to go for the “500 pieces, classic cut” option — and it’s nice to be able to see up close works that I’ve spent hours literally puzzling over. I found Cézanne’s Card Players particularly rewarding, very much more than the sum of its parts. There are plenty of celebrities to spot, as far as that goes — some cool Manet-on-Monet action, as well as an extremely on-the-nose Paul Klee painting titled Oriental-Bliss. And while the world-savior is yet to make His appearance, another Da Vinci — perpetual bridesmaid La belle ferronnière — looks like she is enjoying herself, finally, out from under the shadow of her more famous cousin.

Still, the best part of the museum for me was the eavesdropping. “How surprising to see a Yemeni Torah scroll on display here,” some young Desis murmured, noting its casual placement amid Quranic and Bible manuscripts. How very magnanimous of the Louvre Abu Dhabi to display me here! the Torah seemed to scream back. Elsewhere, a small blond child running in woozy bumblebee motion yelled that he sees naked people. (To be sure, there are quite a few, including a notable pair of artfully fig-leafed male nudes in Greco-Roman style; female breasts, however, are universal.) I especially enjoyed the primal scene of a self-satisfied father, toddler in arms, informing his young offspring that the Van Gogh before them was a Very Important Painting. As so often in these situations, the offspring did not seem to care.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi’s primary curatorial intervention is said to be that, instead of segregating and relegating non-European cultures to their own ghettoized wings and departments, everything here is shown together. This is the museum’s raison d’être, and it has its admirers. Tristram Hunt sees the new Louvre as a “signal renunciation of… colonialism and western cultural appropriation,” a truly universal museum. Mind you, the Louvre Abu Dhabi’s durée is, you know, longue — the past few thousand years, give or take — and over the course of twelve themed galleries, a timeline emerges of history as linear civilizational development. Homo Sapiens emerged, domesticated plants and animals, and built “The First Villages” (gallery one): “The wealth generated by profits from agriculture and livestock supported the birth of the first forms of power.” River systems gave rise to “The First Great Powers” (gallery two) in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley, and “one fundamental invention was writing, which facilitated transactions and helped to legitimize power.” Creativity flourished with the rise and fall of early “Civilizations and Empires” (gallery three). The most common denominator in the human story, it turns out, is power, and throughout the galleries, the wall text is couched in the language of might.

This is true, even, of “Universal Religions” (gallery four), a capacious but undefined category. The Abrahamic religions are singled out for the way they “transcended local cultural characteristics and deeply transformed ancient societies,” even as they encountered and occasionally came into conflict with “other beliefs such as Hinduism in Asia, Confucianism and Taoism in China, Shintoism in Japan, and Animism in Africa.” It is unclear whether these beliefs, tethered as they are to specific geographies, are considered to be universal, but at least everyone gets a spot in the vitrine, if not a seat at the high table.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi’s “integrated” approach can make for interesting juxtapositions, on occasion. And yet by the end of this long march (additional galleries proffer more empires, trade routes, more trade routes, “Cosmography,” and “The Magnificence of the Court”), what remains is very much received history-as-usual, all of it uncritiqued. If it’s too much to ask for a forthright engagement with the horrors of colonialism, war, and the slave trade, could we at least be spared breathtakingly wrong-headed elisions, such as the wall text relating how “the development of means of transport and colonialism impacted all civilizations, which, in return, provided European artists with inspiration.”

One of the museum’s selling points is supposed to be that it updates the idea of the universal museum; unlike the Paris Louvre, Abu Dhabi endeavors to bring the story of art and civilization up to the present day. The evidence so far is not entirely persuasive. A section of one of the penultimate galleries returns to the question of “other beliefs,” except that any pretensions to universalism are dispensed with to present a survey of nineteenth-century French artists responding to what might generously be called “the Mysterious East.” This light-handed approach leads to such labels as “Japonisme, a passion for Japan” to explain Gauguin’s Children Waiting, and “Orientalism, a blend of imagination and knowledge,” to accompany a Delacroix.

Unfortunately, the attempt at universalizing the story of modern art in the twentieth century (gallery eleven) suffers from a related if opposite problem. There is something painfully heavy-handed about the parallels it tries to draw between, say, a Choucair sculpture and a Calder mobile, or between paintings by Mark Rothko and S. H. Raza, hung side-by-side. Visiting art professionals seem to have found these pairings charming, but the unanimous verdict among local art professionals is that the modern gallery is embarrassing. There was a curious lethargy in the presentation, a sort of shruggy ambivalence. The effect is something akin to Leila Pazooki’s 2010 Moments of Glory, an installation that proclaims a neon litany of thin comparisons: “Iranian Jeff Koons,” “Dali of Bali,” “Chinese Gerhard Richter,” “Indian Damien Hirst,” and so on.

The twelfth and final gallery, “A Global Stage,” brought together a quartet of conceptual artists: Ai Weiwei, Zhang Huan, Abdullah Al Saadi, and Maha Mullah. Coming as the close of the chronological art historical journey, with its explicit twinning of culture and power, it seemed to suggest that the future belongs to China and the Gulf. To, say, Abu Dhabi, whose superlatively universal museum is meant to render all those ancient civilizations — not to mention all that French grandeur — very much history.

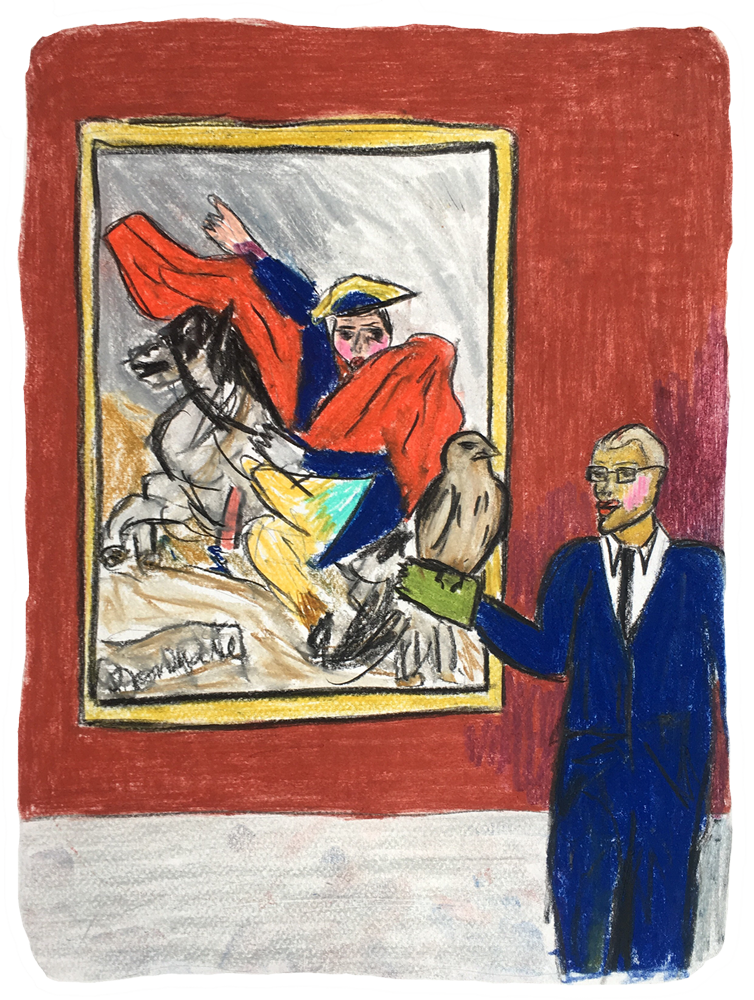

But there are some things money can’t buy. Not yet, at least. That French grandeur — it’s a lot. A couple of galleries in, I began to feel like a duck destined for the foie grasserie, except what I was being force-fed was not corn but an enormous Enlightenment canard. There was something darkly cannibalistic about the whole affair. Take Jaques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps, hung high on its own accent wall in the first of the “modern” galleries (and hilariously side-eyed by a much smaller portrait of George Washington). In this 1803 Versailles version, one of five, Napoleon is the embodiment of France’s imperial dreams, hips swiveled in full disco point, astride a rearing grey Arabian. Now back in the Middle East, centuries later, he still seems to own the place.

France has been grooming this particular horse for some time. The first step was the establishment of an Emirati outpost of Paris-Sorbonne University in 2006, which opened a temporary campus not eight months after the signing of the intergovernmental agreement; it moved into its permanent location on Reem Island in December 2009. Of note is the Sorbonne Abu Dhabi’s master’s program in the History of Art and Museum Studies, which is run in collaboration with the École du Louvre and mandates a semester-long internship at a French museum “to help strengthen relations between French and Emirati cultural institutions.” A dozen years later, many of its graduates can be found occupying senior positions in the UAE’s culture industry.

French soft power was in further evidence in the other current temporary exhibition, ‘Co-Lab: Contemporary Art and Savoir-Faire,’ which paired four local artists with four historic French manufacturers of glassware, ceramics, tapestries, and embroidery. Similar to the ongoing efforts of Italian manufacturing councils — or indeed, of Modi’s “Make in India” campaign — the messaging here was that French fabricators never go out of style. Particularly interesting was Train to Rouen, a collaboration between Vikram Divecha and the architectural textile and embroidery firm MTX Broderie Architecturale. MTX’s office in Paris happens to be a stone’s throw from the Gare Saint-Lazare, immortalized by Monet in a painting that happens to be one of Divecha’s favorites. (It is currently on view elsewhere in the museum.) In Monet’s canvas, light and dark play amid billowing smoke, steam, and clouds beneath the railway station’s vaulting roof. Divecha, a conceptual artist whose work deals with time, labor, and systems, discovered that Monet had successfully petitioned the authorities to delay one train in the station by half an hour, to give him more time to capture the scene in his preferred light. Divecha worked with the French rail company to delay the same train by five minutes, plotting the results as they rippled through the system in an architectural structure that resembles an embroidered musical score. It’s an endearing work, if abstracted enough that the advertised product is less French textiles than France itself. In any case, I was tickled to see an Indian flag pasted up on the studio wall behind Divecha in an explanatory video interview — a pleasantly discordant note, and perhaps even a secret nod to the outsized impact Indian textiles have had on the history of French fashion.

In January 2009, I happened to be in the United Kingdom, visiting a friend at the London School of Economics. There were a number of student occupations at British universities at the time — this was a week or so into the Israeli assault on Gaza — and I arrived just in time to attend the LSE’s. Two things from that day remain indelibly burned into my mind. The first was how polite it all seemed, compared to the militarized face-offs between security personnel and students at American university protests. The other was the moment of shock, as we left the occupied auditorium that first night, that the hall bore the name of the UAE’s founding father, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan al Nahyan. I’d lived in Dubai for most of my life, and it was the first time that Emirati soft power felt like more than an abstraction to me.

But sometimes the velvet frog-tongue glove slips to reveal the proverbial iron fist. Alexandre Kazerouni’s Le miroir des cheikhs, recently reviewed at the Art Newspaper, suggests that the financing of the Louvre (and indeed, the Sorbonne, NYU Abu Dhabi, and the very much unfinished eco-city Masdar) was made possible by the UAE’s Offset Program Bureau, an entity created in 1992 to administer the bounty resulting from offset payments from arms sales. Today, French arms dealers have been deeply involved in supporting the UAE-backed, Saudi-led campaign against Houthi rebels in Yemen.

Meanwhile, the Louvre Abu Dhabi recently drew ire over a museum-drawn map of Iron Age Gulf trade routes that erased the Qatari peninsula. (That the map in question was hanging in the Children’s museum seemed like a bittersweet throwback to my elementary-school days, when you quite literally could not find Israel on a map.) Qatar is the UAE’s great soft-power rival in the region, and things have lately taken a hard turn. The UAE is part of a bloc of countries that has severed diplomatic relations with Doha; Qatar has been subject to an array of economic sanctions for going on eight months now. At the Louvre, happily, the matter was quickly addressed: the museum drew up a new map that fixed what it insisted had been an accidental oversight. But the kerfuffle was a reminder that there’s much more at stake in the soft power sweepstakes than tourism.

The Louvre was announced the year after I first left Dubai, to go to college in the US. Its opening was delayed several times — construction was postponed for several years as the government reprioritized its development strategies during the economic slump that followed the global financial crisis. Officially, the major museum projects associated with the cultural district are still on the books; Saadiyat Island is too big to fail. But all of them were stalled. The Louvre never faced the kind of sustained labor protests that have dogged the Guggenheim — whether this is a sign of that superior French soft-power prowess or lingering post-imperial savoir faire or something else, I don’t know. I guess I always assumed that the British, who ruled indirectly over this place for a hundred and fifty years, would see to it that the Zayed National Museum got built first. The Louvre was a marker of a near-yet-distant future that was probably never going to come to pass. When pigs fly; when salt glows; when hens have teeth; when the Louvre Abu Dhabi finally opens. And then it did. Who knows what comes next?