When I arrived in Los Angeles in the mid-1990s, the highlight of most visits to museums and galleries was picking up the latest issue of Mat Gleason’s Coagula, a free magazine that came out every two months and was left — often by Gleason himself — in big messy stacks beside the front door.

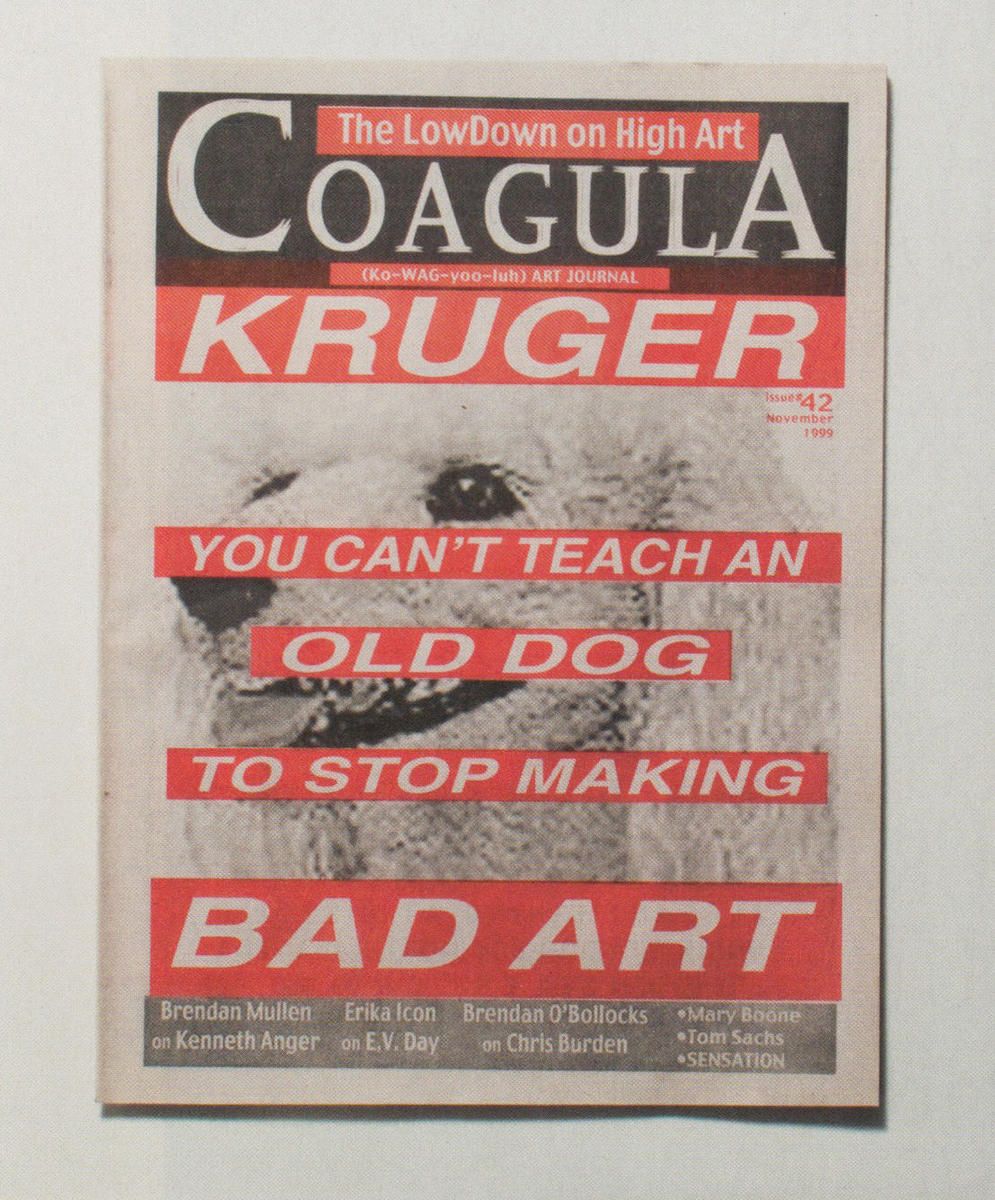

Stapled and printed on newsprint, Coagula looked exactly like what it was: a scurrilous gossip rag, a thorn in the side of the art world’s sacred cows and a salve to the sanctimony of institutional art. The ink from its garishly full-color covers often came off on your hands. Coagula’s print run was a healthy twelve thousand; its readership far exceeded that number. Since the only way of obtaining a copy was an excursion to one of LA’s dull cultural meccas — which, at that time, were almost all inconveniently located in corporate downtown or the far-off west side — the magazine passed hand-to-hand between artists’ apartments, like samizdat.

In order to understand the appeal of the magazine, you’d have to know how monolithic and boring the Los Angeles art world was then, with its handful of players ensconced in key institutional posts. As Gleason notes, “When it first came out, people in New York were like, What the fuck? It could never have happened in New York. Back then, LA was like the Wild West.”

A self-confessed “really bad painter,” Gleason discovered his talent for journalism as a fine arts student at Cal State, Los Angeles, where he wrote an arts column for the student newspaper that gradually morphed into periodic “reviews” of the Cal State administration. Banned for life from that paper, he founded his own. After graduation, recognizing the chance to create a punk zine for the art world, he started Coagula with $1000, proceeds from a good bet on the 1992 Super Bowl.

Influenced equally by Mad magazine, the National Enquirer, and the muckraking investigative journalist I. F. Stone, Gleason has passionately ridiculed the ridiculous and promoted the unsung for two decades.

A typical Gleason exposé involves calling a spade a spade. An anarchist to the bone, Gleason was quick to pick up on the, umm, dissonance between the anarchic ethos of street artist Banksy and his blue-chip career. “I can smell a poser,” Gleason explains. “If I can’t do anything else, the art world needs that.” “Nothing About Banksy In This Issue!” a 2003 Coagula cover proclaimed. Instead, Gleason assembled a group of one hundred under-recognized artists and photographed them en masse, holding up signs with their names. “The point is,” he once told Tom Patchett, “there are people in power, and there are people who aren’t in power who are going to try to point out why the people in power are wrong. And I’m not in either camp. The goal of Coagula is not to destroy the academy to become the next academy.”

Targeting curators, gallerists, and overrated artists alike, Gleason’s prose is scabrous, excessive, and pointedly eloquent. He never backs off from voicing opinions that others consider best left unsaid. His taste is eclectic. Coagula has consistently championed the work of Karen Finley, who for a while contributed a cartoon called “Karen Finley’s Funnies” and graced the magazine’s cover three times. But reviewing the MOCA retrospective of her close contemporary Barbara Kruger, Gleason observed that the artist “offers simplistic catch-phrases in lieu of activism. She comes from the decade that invented the sound bite, and it shows! Adding a very ’80s ‘post modern twist’ the catch-phrases are often just vague enough to apparently shock us!… Perhaps in fifty years, one of these will hang next to I Want My MTV in the Reagan Library.” Reviewing Most Art Sucks, Coagula’s 1998 anthology, David Bowie summed up the project: “Cruel, insensitive and thoroughly enjoyable!”

Thankfully, and perhaps in part due to Coagula’s intervention, the art world in Los Angeles has become more pluralistic. In 2009 Gleason changed the magazine’s format to online and print-on-demand, thus reaching a far wider audience. Twenty years after its founding, Coagula remains outrageous, engaging, and completely apt. Always the contrarian, in a recent issue Gleason embraces his old bête noire, megagallerist Jeffrey Deitch, upon his appointment as chief MOCA curator. “They’ve been whores for years, why not bring in a top pimp to get that brothel rockin’?”