Murcia / Cartagena

Manifesta 8

Various venues

October 9, 2010–January 9, 2011

In its fifteen years of existence, Manifesta has become known for a number of different things. The most obvious is the nomadic nature of the so-called European Biennial of Contemporary Art. Also, Manifesta’s mandate — to question what Europe means and where its borders lie, in geographical, political, social, economic, psychological, cultural, and artistic terms — has been fairly well established by now, although there is an equally evident disjuncture between Manifesta’s interest in situating itself in close proximity to conflict, and its seemingly unfailing ability to take up residence in rather affluent, prosperous, and relatively strife-free locales. Moreover, Manifesta has consistently proven itself a laboratory for curatorial thought and a platform for young and emerging talent.

With each subsequent iteration of the event, however, Manifesta runs the risk of fetishizing practices that are often not so very new, and wherever there is a fetish, there is usually a falsehood lurking close behind. Unfortunately, falsehood was a factor multiplied many times over by Manifesta 8, which took place in the southeastern Spanish cities of Murcia and Cartagena from October 2010 through January 2011.

The first problem was the idea that Manifesta 8 was curated by three curatorial collectives. Never mind that collectivity has been celebrated — for the mere fact of existing rather than for what it may actually produce — far too much and for far too long in contemporary art as a kind of antidotal plasma for the ruthless individualism of the market. At least one of three groups brought onboard to fill up the event, the Alexandria Contemporary Art Forum (ACAF), cannot accurately be called a curatorial collective at all. ACAF is first and foremost a space, an elegant old, eight-room apartment in the Azarita district of Alexandria, run by Bassam El Baroni, Mona Marzouk, and Mahmoud Khaled, among others. To consider it anything else is to overlook, ignore, and undermine its reasons for being and much that it has accomplished in the five years since it opened its doors in Egypt’s second largest city.

Secondly and more substantially, the notion that this edition of Manifesta was staged in dialogue with North Africa was a stretch, to be generous. Murcia may have been founded as a Moorish city more than a thousand years ago, but today, it isn’t exactly the focal point for North African immigration to Spain, nor is it the place where the politics of such immigration — or religious freedoms vis-à-vis Islam, or discriminatory policies against European citizens of North African or Arab ancestry — are most palpably felt. Murcia’s Minister of Culture had very little to say about the North African component of the event in his text for the catalogue. To the contrary, he wrote of the positive effects that the Manifesta “brand” would have in making his region a destination for cultural tourism.

This is not to say that Manifesta 8 should have been obvious or literal in seeking to “engage” North Africa. But if you are going to propose a framework as absurd as a nomadic European biennial having a one-sided conversation with the top half of a continent, you had better back it up somehow, lest it come across as a token gesture — which, of course, it was. To their credit, all of the curatorial teams involved seemed to ignore it, reroute it, or make of it something far more complex, riddled with suspicions and presumptions, layered with subtlety and nuance.

ACAF, tranzit.org, and the Chamber of Public Secrets (CPS) also rained on the collectivity parade by organizing three wholly independent and distinct projects. If anything, the entire Manifesta edifice looped awkwardly and elliptically around two distinctly phallic points — one being Banu Cennetoglu and Shiri Zinn’s delicate glass cremation urn filled with dust from the exhibition site and shaped like a life-size penis, the other being Simon Fujiwara’s enormous sculpture of an even more enormous penis, an alleged recreation based on eyewitness testimonies of an undocumented Nabatean rock formation said to have been discovered by British construction workers beneath the site of a new museum being built somewhere in the Arabian desert. (“Size is not the question here. It’s the shape that counts. Cock or not?”) Clever that, but the twinning of these two pieces was probably just an accident.

To experience these three separate exhibitions as exhibitions was a bit unfair to CPS, which invested much of its energy in mass-media interventions, and thus fell outside the time and space of the biennial proper. Tranzit.org approached the rickety construction of Manifesta 8 by creating a game of compare and contrast between post-communism and post-colonialism, which provided broad cover for a fairly standard, by-the-book biennial show of leveling hits and misses, gleaming gems, and utter dreck.

Among the knockouts were Tris Vonna-Michell’s Balustrade (2010), an appropriation of two rooms in a former artillery barracks (one for a derelict office as installation, the other for a mesmerizing slide-show projection with seemingly random voiceover narration) and the Otolith Group’s new film Drexciya Mythos, Part 1 (2010), a slippery and elusive piece that sets out to investigate the mental and material contours of Drexciya, a pair of Detroit techno pioneers, active in the 1990s, who took their name, and devoted countless albums and EPs, to the sci-fi inflected myth of an Atlantis-like underwater country called Drexciya, inhabited by the unborn children of pregnant women who were thrown to their deaths from the ships servicing the African slave trade. Gorgeous footage of rock formations and the sea folds around strangely archaic song and a dense, mysterious, ultimately fascinating (if entirely inconclusive) story about an author losing the proverbial plot.

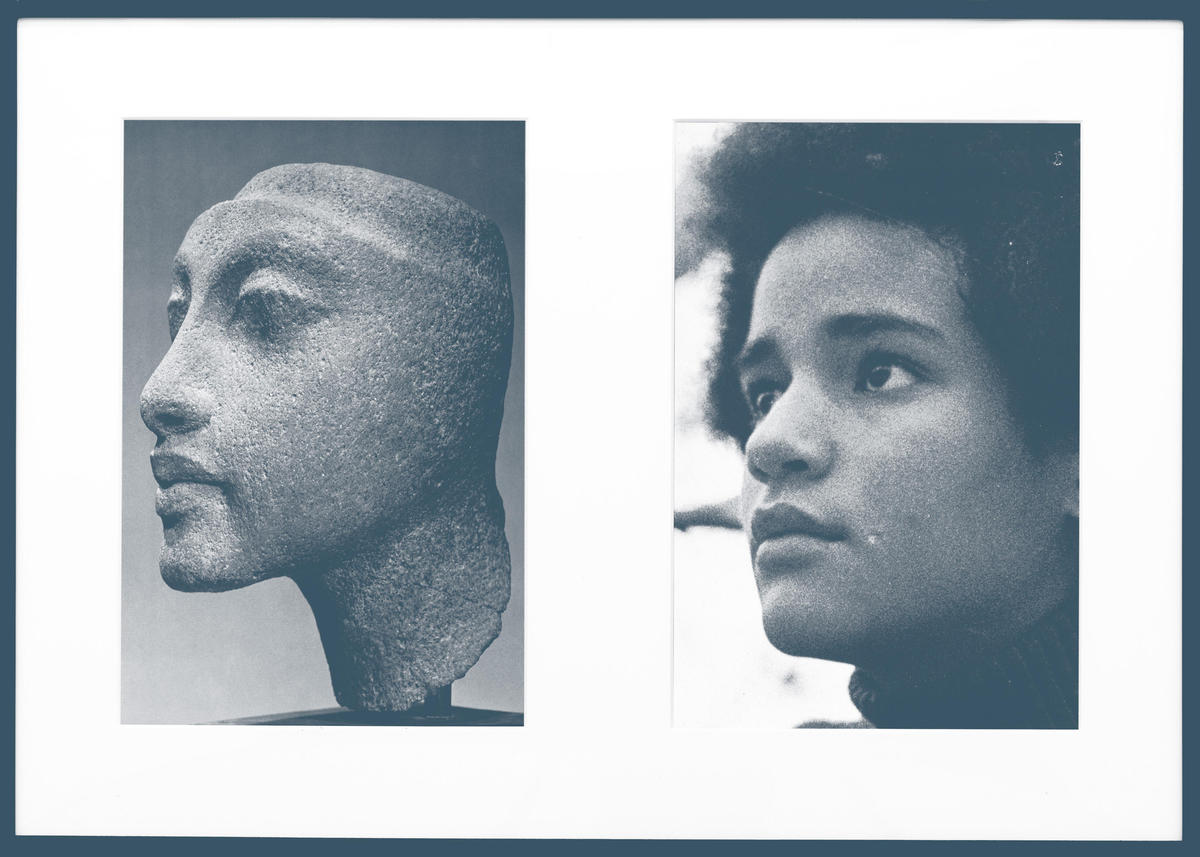

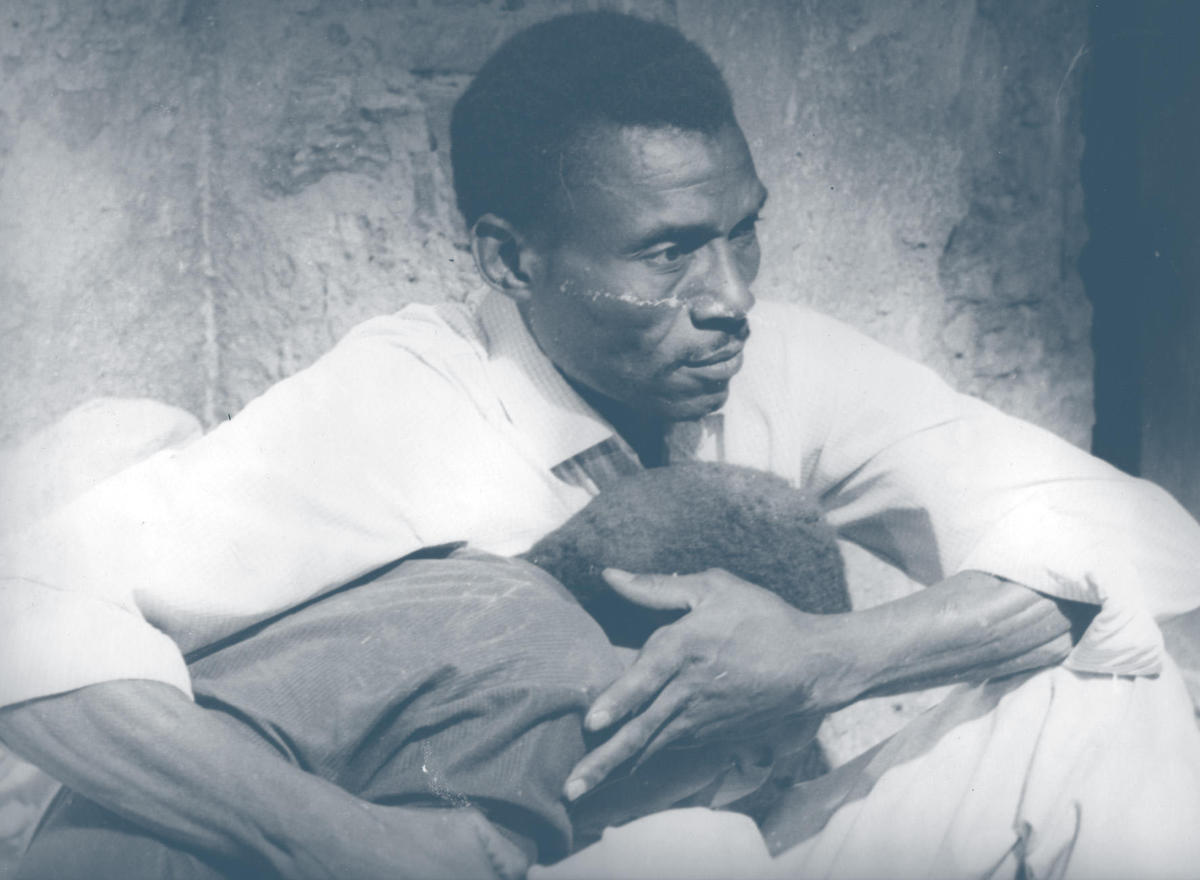

Elsewhere in tranzit.org’s exhibition was Matthieu Kleyebe Abbonenc’s presentation of Sarah Maldoror’s riveting 1969 film Monangambée. Maldoror, who was born in France and continues to live and work in Paris, spent much of the 1960s and 1970s making films about — and immersed in the aesthetic of — African liberation movements. Abbonenc’s installation includes visual material from the journal Tricontinental and a stack of gigantic posters for Monangambée. The wall text tells you that Abbonenc is searching for a copy of Maldoror’s Guns for Banta, seized by the Algerian government in 1971.

In a somewhat similar vein, Catarina Simão’s installation Off Screen: On Mozambique Film Archive (2010) jammed a building’s worth of material related to Mozambique’s state-owned film collection — interviews, video footage, film fragments, press clips, folios, and files — into a single room, and basically left it at that. The problem is that both of these projects, as they were presented in such a crammed context, felt like fleeting introductions. Maybe you shook hands. Maybe you got the name. Maybe you’ll even remember the face next time you meet. But this hardly counts as a meaningful encounter, and it’s a long, long way from serious engagement. If there’s been a shift in the experience of contemporary art over the years from seeing an object as art in an art space to seeing the documentation of an action as art, then we now seem to be moving through another transition, from seeing the documentation of an artwork completed, to confronting the research material for an art project that has yet to begin. A call to find a missing film, a roomful of records with virtually no conceptual thread — this seemed lazy rather than challenging or edifying.

Certainly, research-based practices are here to stay. But consider these two examples set against ACAF’s installation of a single research project, The MoCHA Sessions, in a single space. Here were the archives of the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, which rose to prominence and fierce political relevance in New York in the 1980s and then crashed and burned just five years after it opened. Those archives were the source material for a series of six different exhibitions by six local artists, opening for about two weeks apiece over the course of three months. Not only was the space conducive to study and reflection, the material felt alive, the various connections drawn across time, history, and the politics of art meaningful and provocative. The MoCHA Sessions also nestled into ACAF’s overall project an interest in revisiting the legacies of identity politics and institutional critique as it ricocheted around the culture wars of the decade that preceded the fall of the Berlin Wall, the foundational moment that gave Manifesta its raison d’être, to probe the substance of post-Wall Europe.

This concern for pre-Wall financial badlands also echoed through Hassan Khan’s single-channel video Muslimgauze R.I.P., one of three related works, which digs into the dustbin of recent history to consider the fascinating case of a radical musical genius born and raised in Manchester, in the hard, depressing years of Margaret Thatcher’s rule. If you draw a line from The MoCHA Sessions through Khan’s work to another exhibition entirely, Tania Bruguera’s Huelga General, one in a series of single-artist shows collectively titled Dominó Caníbal and curated by Cuauhtemoc Medina for PAC Murcia, overlapping with but totally separate from Manifesta itself, you find a set of powerfully relevant and politically charged ideas about art, life, capital, and the capacity for action amid harsh economic conditions and unkind financial policies that affect us all, before the Wall, after it, and a good long distance from it.

Of course, Manifesta isn’t a competition, but with three projects stacked up side by side, there is an irresistible temptation to keep score. ACAF pulled off a remarkably strong and uncompromisingly complicated project, replete with a full-blown “theory of applied enigmatics” to support it, in the midst of a logistical and organizational nightmare. For that is the other thing for which Manifesta has become known — reeling artists and curators into a bureaucratic clusterfuck. During the preview days I heard at least five variations on the following theme from frustrated artists and curators: “I live in a third-world shithole, but at last I can get things done there.” So much for cultural dialogue.

Five years ago, the organizers of Manifesta published a hefty volume of curatorial thought entitled The Manifesta Decade. It’s an invaluable resource in a field that has generated a lot of talk about the so-called biennial phenomenon without much serious analysis circulating in print or bound between hard covers. One of the more critical essays in the book, by Camiel van Winkel, states: “Manifesta is an institution built on the critique of institutions.” From the beginning, it was meant to challenge existing large-scale international exhibitions that were “inadequate to respond to the political, social, and cultural changes that had taken place in Europe after the collapse of the Warsaw Pact in 1989. Manifesta was thus founded as an alternative to institutions like the Venice Biennale and Documenta, which were seen as slow, bulky, bureaucratic, inefficient, and implicitly nationalist… Manifesta was launched with the ambition that the institutionalization of this new biennial would remain limited; it would never suffer from the inertia and massive scale of its counterparts.” Never say never. In spite of itself, and to the detriment of some of this edition’s less fuzzy-headed artists and curators, Manifesta has become the very thing it never wanted to be: too big, too bloated, and too reticent to really wrestle, much less precisely name, the political crises that motivate its existence.