Like the quark and the Higgs boson, the breastplate of the archangel Metatron belongs to that class of objects knowable only through their remote effects. No human being has seen it, save possibly Abraham, who may have been distracted by its glory as he prepared to slide the knife into Isaac’s throat. Its owner may be the same angel who wrestled with Jacob at Peniel, but it is hardly credible to think that Jacob would have noticed what his adversary was wearing, not least because it was night. It may have been Metatron whom the Lord sent forth to keep watch over the Israelites as they stumbled through the wilderness, but he would have appeared to them only as something vast and shining, less angel than beacon. In the midst of all that radiance, who could make out a breastplate?

These are the only recorded instances of Metatron’s appearance in the human world, and they’re all apocryphal, arising from the Bible’s reticence and the taxonomic frenzy of certain of its commentators, who composed a biographical note for every walk-on in Scripture. Most of what we know of Metatron comes from such noncanonical sources as the Talmud, the zohar, and the Hebrew and Ethiopic books of Enoch. He is variously described as the king of angels, prince of the divine face, chancellor of heaven, angel of the covenant, and the “lesser YHWH.” Some traditions make him a stenographer or scribe. After glimpsing him seated in heaven, a privilege forbidden to all but God, one of the Talmudists speculated that Metatron was “another power” equal to the Creator. Other commentators insist that he was just taking notes and demonstrate the angel’s subordinate status by suggesting that he was beaten with fiery rods. He is sometimes said to be as old as the created world, or older. But yet another story insists that he began his existence as a man, Enoch, who walked with God and then, as Genesis puts it, “was not.” Once in heaven, writes Gershom Scholem, “his flesh was turned to flame, his veins to fire, his eyelashes to flashes of lightning, his eyeballs to flaming torches.” The new being was more powerful than any other angel and as tall as the earth is broad. And he was called… Metatron. The parallels with superhero origin stories are striking; no wonder that the Japanese adopted him as a super-robot, or that entities bearing his name keep popping up in video games and cartoons across the globe.

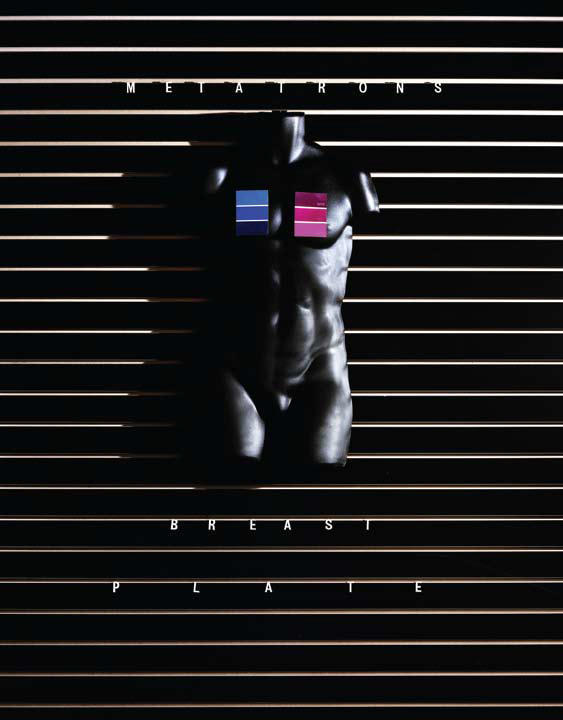

Like any proper superhero, Metatron has a power object, a breastplate. It is said to be similar to the one worn by the high priest of Jerusalem in the first temple. In some commentaries, it is that breastplate’s archetype, the idea of an archetype having come to Judaism from the same Greek sources that imparted it to Christianity. The high priest’s breastplate was not just a ceremonial garment but also a prophetic instrument. It contained twelve stones, arranged in rows, each engraved with the names of one of the twelve tribes and one of the twelve patriarchs. During periods of crisis, when the ordinary human wisdom of kings and rabbis foundered, the high priest would ask the breastplate a question and certain letters in the stones would light up. The priest would note these and arrange them into a word that indicated what course of action Israel should take: “war” or “peace,” “plant” or “pluck up,” “kill” or “heal.” It is speculated that the famous third chapter of Ecclesiastes, which begins “To everything there is a season,” is a list of such instructions.

The relation between an archetype and its earthly occurrence is the relation between an original and a copy, with the copy of necessity grossly inferior to its source. Relative to Metatron’s breastplate, the chest piece worn by the high priest was a tinfoil-wrapped cardboard box with Christmas-tree lights for stones. Its oracles were as accurate as a Magic Eight Ball. Dominionists of every faith forget that the tragedy of the sacred state is that it can never be more than a blurred offprint of the kingdom of heaven. What remains mysterious is how the archangel’s breastplate figured in Israel’s auguries. Was it a transmitter that picked up the high priest’s request, forwarded it to the Almighty, and encoded the divine response into pulses of light, which it then sent earthward? And can we be sure that the answers came from God and not from the angel? As the story of Lucifer attests, angels can have ideas of their own.

In Platonic philosophy, the archetype predates its earthly translations. In Jewish mysticism, however, the opposite is sometimes true. The archangel’s breastplate, forged from the unimaginably heavy ore of the sun and set with stars, could not come into being until the high priest’s had been stapled and taped together from its flimsier materials. The breastplate of the high priest was less a copy than a prototype, a ham-handed foray toward an as-yet unrealized perfection. As the zohar tells us: “The impulse from below calls forth that from above.”