For a long time, Mingering Mike was one of the greatest musicians no one had ever heard of. Based in Washington, DC, he released a hundred or so singles and albums between 1968 and 1976. The sleeve of his first record, recorded under a pseudonym, bore a testimonial from comedian Jack Benny: “GS Stevens is a bright and intelligent young man with a great, exciting future waiting him.” It added, with mysteriously erratic spelling, “But I hope he can make it in show biss so he can pay me for this fine, outstanding introduction if I do say so myself.”

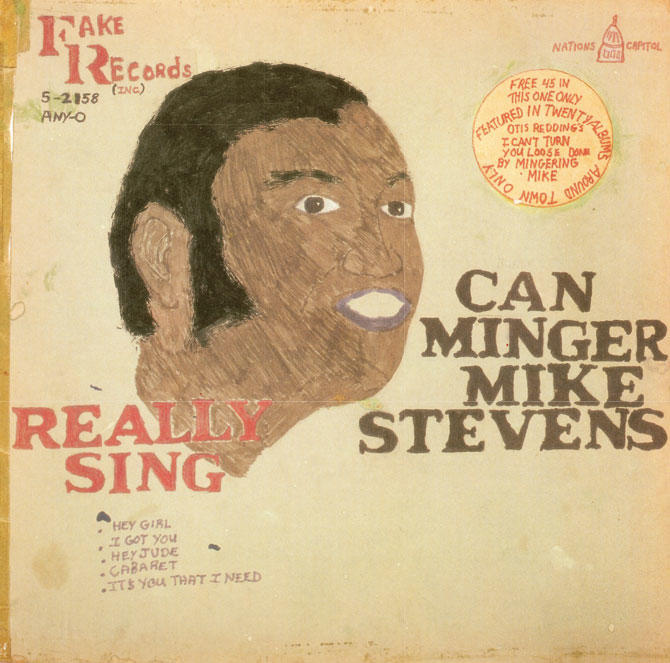

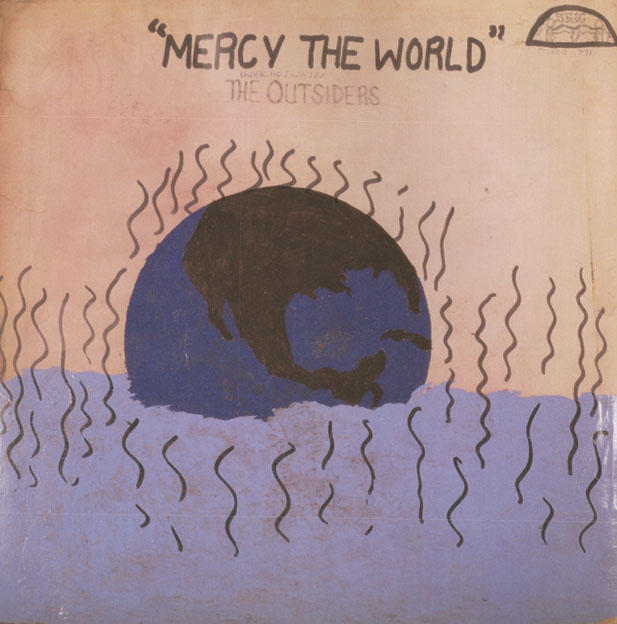

His output over the following years was phenomenal. He established more than thirty labels, with names like Ramit, Puppy Dogg, Mother Goose, Sex, and Fake, and recorded as Mingering Mike, Mingering Mike & The Vangoes, and The Mingering Mike Singers & Orchestra. Many of his tracks feature long-time collaborator The Big D. His range was extraordinary, covering everything from funky soul and protest ballads to blaxploitation soundtracks, Bruce Lee tribute albums, and comedy platters (In My Corner by Rambling Ralph includes the unforgettable cuts “Sometimes I Get So Hungry I Can Eat a Light Bulb, Or My Chair, Or Even My Hair” and “You Don’t Have To Wake Me, The Aroma Will Do That”).

Occasionally the composer became cocky; Live From Paris, a sickle-cell anemia consciousness-raising triple album by the Mingering Mike Revue All Decision Stars, bore the slogan, “This is Minger’s second live album and it’s so brilliantly good that they couldn’t help but to put three albums in this pack.” Throughout his career, he displayed the kind of insouciant charm evident in his handle. While black musicians from Count Basie to Duke Ellington to Prince Paul have brashly adopted self-aggrandizing new names, Mingering Mike gave himself a moniker that sounds like a schoolyard insult.

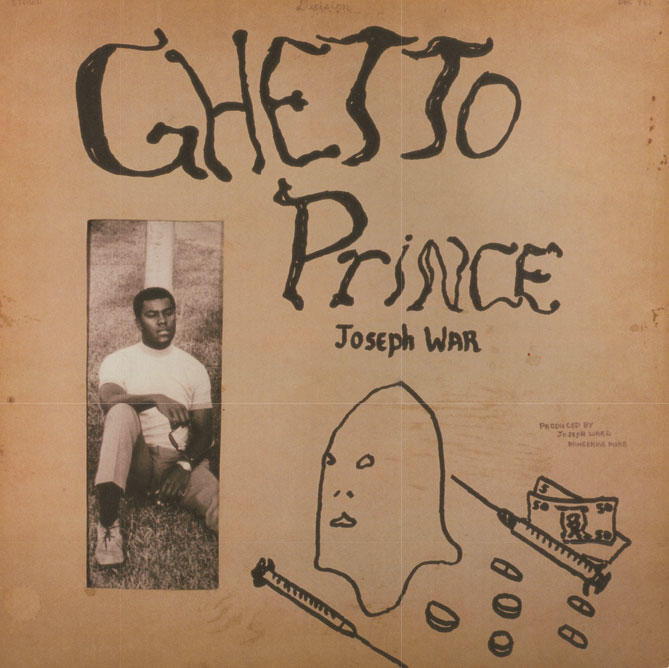

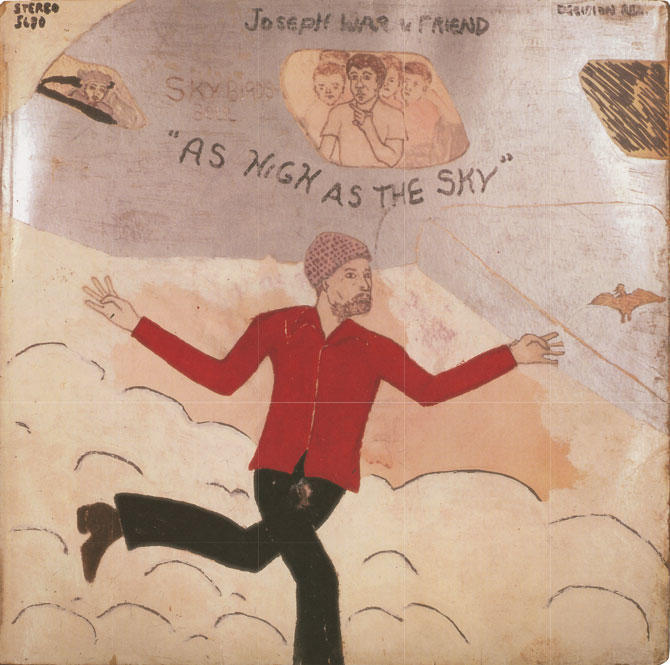

As it happens, there’s a good reason why critics and historians have generally shunned Mingering Mike’s music: It never existed. Or rather, each of his records was produced in editions of just one copy. Nor were they pressed on vinyl, being issued instead on pieces of cardboard, the grooves carefully etched with glossy paint, the handmade label glued on. Each record contained a catalogue number, liner notes, and sometimes even a fan club address. The sleeves, drawn in lively and colorful, though rather rudimentary, fashion, show him perched before trees like a black Nick Drake, busting disco moves with a pal in front of the White House or performing on stage before adoring audiences.

Most of the collection was held in a storage unit in Washington — until Mike failed to keep up with the rental payments. His records disappeared, only to be rediscovered a couple of years ago in a flea market by a private detective named Dori Hadar. Now the sleeve art has been made public in a volume from Princeton Architectural Press that also furnishes some biographical shards about Mingering Mike, or Mike Stevens, as he was known to his mother. He had four older brothers and sisters with whom he played a few shows at old folks’ homes and at a local mental hospital. He was conscripted during the Vietnam War but soon deserted.

It can be tempting to view Mike’s self-taught and occasionally outlandish work as an example of “outsider art.” (One of the contributors to the book does just that.) It’s certainly possible to read a lot into album titles such as Fractured Soul and Other Wise, or into the notes accompanying 1975’s Isolation LP: “Dedicated to my dear troubled kin and to anyone else whom once was, but not, anymore…. You can only dig it if you’ve been there.” Yet Mike’s work lacks most of the visual and textual tics characteristic of “outsiders”: extremism, expressive density, love of montage, psychosis, trauma. Rather than laying bare its askew isolationism, Mike’s work places him within a community — albeit an imaginary one — populated by fellow musical creators and producers.

The mere fact of his work’s survival is a delight. His oeuvre shares certain features with other music of the period, from the jazz and soul artists of late 1960s Addis Ababa to the multifarious reggae stylings that gushed out of Kingston, Jamaica, in the early 70s. Many of the era’s most extraordinary songs were recorded on wafer-thin vinyl that crackled like a frying pan and was issued in flimsy sleeves full of runny colors, made from recycled sugar boxes. Compared to the marketing department-led opulence and choreographed moodiness of today’s glossy CD jackets and videos, Mike’s work seems prelapsarianly moving.

Still, there’s a market for innocence, just like anything else. Mike’s work is represented by the Hemphill Gallery in DC, which is hoping to sell it to a museum or archive that will see it as part of, rather than a deviation from, postwar African-American expressive culture. It also turns out that David Byrne, formerly of the Talking Heads, is putting together an album in which Mike’s songs, so long alive only in his dreams, will be notated and recorded by a slew of handpicked superstar artists. There are even plans for a concert in New York. At long last, Mingering Mike may actually be on the brink of the “great, exciting future” he conceived for himself forty years ago.