Molla Nasreddin: The Magazine That Would’ve, Could’ve, Should’ve

By Slavs and Tatars

Christoph Keller Editions

JRP-Ringier, 2011

Molla Nasreddin receives an illiterate man, who requests that the cleric read a letter for him. Nasreddin examines the letter, looks up at the man, and admits that he can’t read a word of it. “Shame on you,” the man cries. “You should be ashamed to wear your turban!” And so Nasreddin removes his turban and places it on the man’s head. “Now you’re wearing the turban. Why don’t you read the letter yourself?”

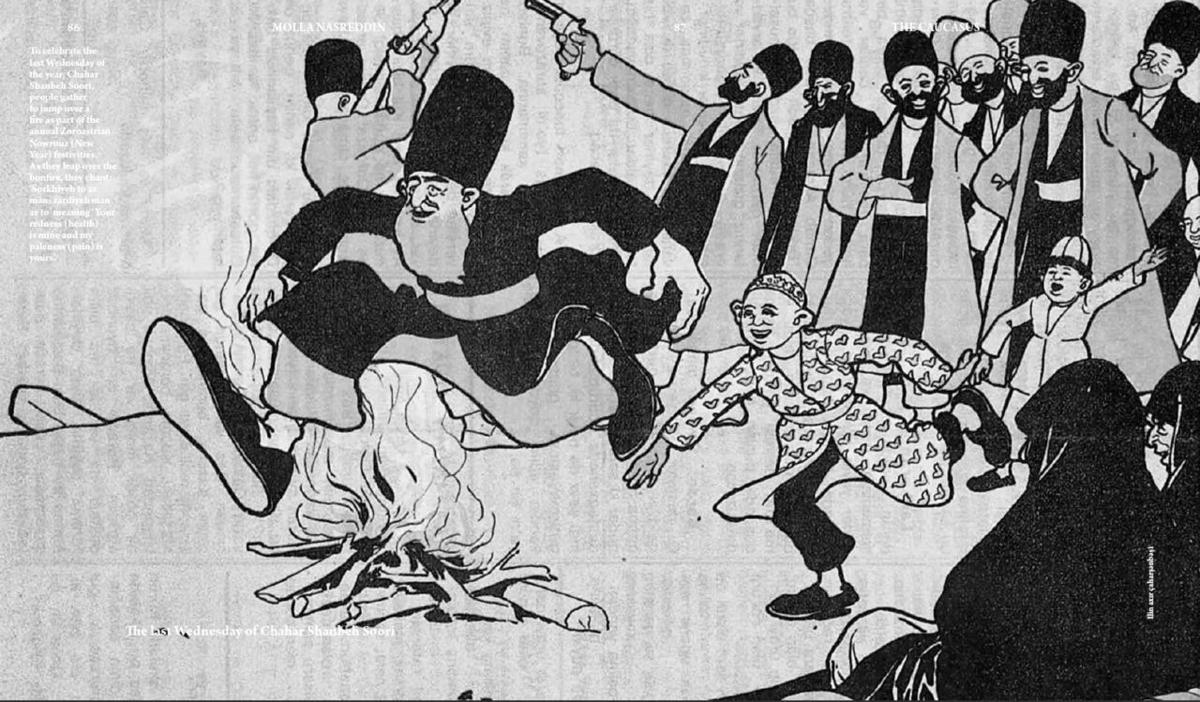

So goes one of the myriad stories of the legendary holy fool, believed to have lived in rural Turkey in the 1200s. For hundreds of years, stories of the cleric — a congenial middle-aged man pictured in a robe, slippers, and turban, oftentimes with his precious donkey and wife — have circulated throughout the Muslim world and The Caucasus, from Turkey to Greece to Kazakhstan to Tajikistan. Nasreddin has provided a kooky brand of commoner’s wisdom — Confucius meets Charlie Chaplin — and witty send-ups of the selfish, cowardly, incompetent, corrupt, and ignorant. Nasreddin is particularly popular in Azerbaijan, where, in 1906, writer Jalil Mammadguluzadeh founded a journal named after him, published, most unusually, in Azeri (though it also contained Russian, Farsi, Ottoman Turkish, and Arabic). Molla Nasreddin, an eight-page satirical weekly, printed essays and poetry, mock telegrams between members of the elite and tongue-in-cheek open letters to readers, as well as incendiary cartoons skewering establishment politics and culture. The magazine was based in Tbilisi, polyglot and cosmopolitan at the time, with a population that looked toward Iran religiously, Moscow politically, and Turkey linguistically; liberal intellectuals thrived in the region, known as Transcaucasia, thanks to the Russian Czar’s decision to exile subversives there. (Transcaucasia was known as “warm Siberia.”) Within months, Molla Nasreddin’s circulation reached 5,000, with readers from Morocco to India and beyond. The magazine became what is almost certainly the first Turkic, Islamic, secular, progressive, transnational literary sensation.

Molla Nasreddin: The Magazine That Would’ve, Could’ve, Should’ve collects scores of the magazine’s illustrations, with translations of their texts and contextual information, prefaced by a breezy introductory essay. According to Slavs and Tatars, the geographically dispersed but Eurasia-centric collective behind the book (and occasional Bidoun collaborators), “Molla Nasreddin managed to do in a pre-capitalist world what today’s media titans, in an uncertain, post-capitalist world, can only dream of: speak to the intelligentsia as well as the masses.”

Along with his partner Mirza Alakbar Sabir, the luminary of literary Azeri realism and incisive polemicist, Mammadguluzadeh distilled the complexities of a world undergoing violent transformations in simple, but highly coded, cartoons. These made up half the magazine, allowing Molla Nasreddin to reach illiterate audiences. Using stock characters, simple illustration, and a symbolic language taken from folk tales, the cartoons attacked traditional religious mores and unyielding authoritarianism; the hypocrisy of the clerics and the oppression of women; the Islamic world’s general inadequacy when compared to Europe; and Western imperialism (and Eastern complicity). Perhaps the most emblematic cartoon is from 1909. Two robed old men, one wearing a taqiyah and waving a stick and the other wearing a cleric’s turban and wielding a club — they are marked “old traditions” and “old sciences,” respectively — are planted on a set of tracks, hands locked, facing down a train labeled “progress.” They exclaim, “We won’t let you move forward.” As in all such drawings, Molla Nasreddin himself observes the action from a distance, his hand gesturing toward the scene, equally amused and chagrined.

Molla Nasreddin moved to the northern Iranian city of Tabriz in 1921, then to Baku the following year, where it was published sporadically, under increasing pressure to toe the Soviet party line, until finally shutting down in 1931. In the editorial from the first issue, Mammadguluzadeh had written, “I persist, because sages pronounce: direct your words to those who do not listen to you.” Ultimately, Molla Nasreddin won the ears of too many, and suffered for its influence, and yet by the time of its demise imitators had appeared throughout South Asia, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe.

It is perhaps indicative of the deft hands of the artists (who are never identified) that the illustrations in Molla Nasreddin often require some serious elucidation in order to be understood by the contemporary reader — occasionally, so much as to deflate the joke. For instance, one cartoon shows a bearded peasant kneeling before a giant hen with the face of a man; two broken eggs sit beside its chest, and a whole egg is covered by its feathers. “The hen is a representative of the Third Duma and has already broken the First and Second,” Slavs and Tatars explains, which illustrates “Russia’s difficulties in moving towards some element of representational government.” Sometimes these one-paragraph explanations are frustratingly, if necessarily, dense; other times there is too little information (the lack of dates is often conspicuous), and the jokes remain obscure. Additionally, the absence of any translations of articles from Molla Nasreddin, or at least images of the magazine in its entirety, leaves the cartoons feeling slightly unmoored — and also leaves the reader wanting a complete translation of the magazine’s print run.

Nevertheless, the brilliance and singularity of Molla Nasreddin — there was no equivalent in the US; imagine Mad merging with the muckraker McClure’s and it somehow working perfectly — is apparent on every page of this book. And while the magazine’s clash-of-civilizations mentality and total faith in the transformative power of reason now seem antiquated, the Great Game persists under other names, the relationship between traditional Islamic countries and modernizing forces remains as tense as it is farcical, and the need for astute criticism and comic relief has not been mitigated in the last century. In short, Nasreddin is with us still, peeking through a window or doorway, faintly smiling at our ridiculousness.