Athens

The 3rd Athens Biennale: Monodrome

October 23–December 11, 2011

A red paintball explodes bloodily against a Greek riot cop’s shield. A woman in sunglasses and a tailored business suit projectile vomits outside a posh boutique. Unappetizing slop (overcooked lentils? human shit?) is spooned into a plastic bowl in some kind of emergency kitchen. A TV set is flung from an apartment window. A masked anarchist lets fly with a Molotov cocktail in the manner of Kobe Bryant delivering a slam dunk in a Nike commercial. A male mouth expectorates a wet puff of tear gas as though it were smoke from a spliff.

Although director Giorgos Zois’s TV trailer for the 3rd Athens Biennale was withdrawn by Greece’s National Television Network (ERT) soon after it was first broadcast, it survives on a YouTube page that also contains links (mysteriously generated by the same complex algorithms that group together videos about pets or Rebecca Black parodies) to amateur and professional footage of violent clashes between Athenian police and the city’s youth. Unlike these reports from the front lines of the Greek financial crisis, Zois’s trailer is composed of six clips of very obviously staged actions, filmed in slow motion and set to a menacing electronic soundtrack.

So tonally different is this film from the thoughtful, melancholy, and elegantly installed Biennale it supposedly promoted that it was hard not to read it as satire or a deliberate exercise in misdirection. If the trailer promised to sate an appetite (not uncommon in the art world) for the empty calories of disaster tourism and highly aestheticized soixante-huit faux-stalgia, the exhibition itself provided sustenance of a very different sort.

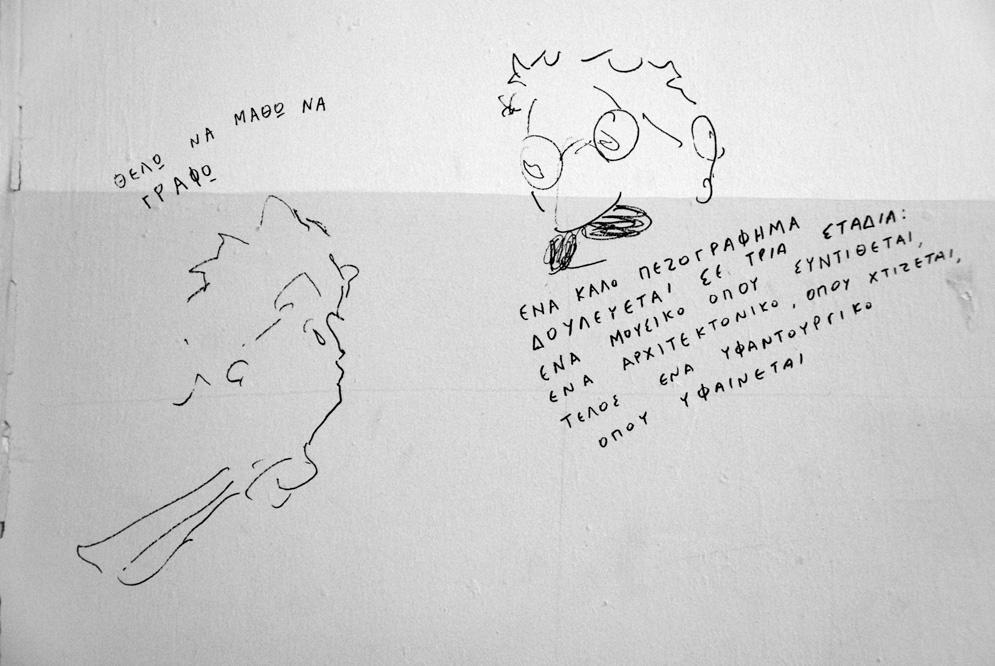

Featuring work by over one hundred artists, the 3rd Athens Biennale assembled, as its curators Nicolas Bourriaud, Xenia Kalpaktsoglou, and Poka-Yio stated, “diverse pieces of an exploratory puzzle, addressing the ‘here and now.’” The exhibition’s title, “Monodrome” (roughly “single track” or “single field”), worked hard, evoking the belief, repeated ad nauseum by the European Union, the IMF, and the Greek government, that the “one way out” of Greece’s present economic predicament is the piling of pain on intolerable pain, while simultaneously positioning the “Greek example,” so often referred to by other nervous capitalist states as a purely local phenomenon, as part of a wider global malaise. “Monodrome” might also be understood as a translation of the title of Walter Benjamin’s One Way Street (1928), a book that begins with the observation that “the construction of life is at present in the power of facts far more than of convictions” (plus ça change…) and whose author was, along with the protagonist of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s novella The Little Prince (1943), one of an odd-couple pair of ghosts who haunted the show, appearing in several graffiti portraits daubed on the walls of the Biennale’s exhibition spaces by artist and co-curator Poka-Yio as figures of the intellectual in retreat and of the innocent, questioning child. Methodologically, “Monodrome” also owed much to Benjamin. This was nothing if not a show of footnotes and fragments, of ruins and dust.

Athens is a private biennale, founded at the tail end of the last economic boom by Kalpaktsoglou, Poka-Yio, and Augustine Zenakos. Given Greece’s near-bankrupt economy, it’s unsurprising that its third iteration (the concluding part of a planned trilogy that also included 2007’s Destroy Athens and 2009’s Heaven) was put together on a hope and a prayer. Accordingly, the show had no catalog and few works that required much in the way of shipping; it made necessarily inventive use of found objects and archival material, programmed its lively events strand on a mostly ad-hoc basis, and was staffed largely by unpaid volunteers. The main venue, a vast abandoned former arts and crafts school in the depressed Psyrri neighborhood, was left much as the curators found it, complete witah peeling paint, graffitied walls, and chalk-scrawled blackboards. Even the desiccated corpses of unlucky pigeons were preserved by the biennale team under gleaming bell jars, “Greek examples” that had reached a dead end, contained for analysis and as proof against contagion. Into the building’s pedagogical husk the curators introduced a number of works that pointed, obliquely or not, to lessons learned and forgotten, stories told and retold, and to energy expended and never recouped.

To pass through the former school was to adopt the persona of a new pupil, wandering from class to class, half-wary, half-hopeful. Economics of course made up much of the curriculum here, whether in the form of Michalis Katzourakis’s series of paintings of boarded-up shops, Windows (2007); Andreas Lolis’s empty cardboard boxes carved from marble, Untitled (2011); or Liam Gillick’s Inside Now, We Walked into a Room with Coca-Cola Coloured Walls (1998), a series of reddish-brown brushstrokes applied to the building’s plasterwork in a failed attempt to replicate the precise shade of the world’s favorite fizzy drink. Natural history, and a sick kind of ethics, was taught by means of Jean Painlevé’s extraordinary black-and-white film Le Vampire (1945), in which a bloodsucking bat boogies to a Duke Ellington soundtrack, and also by an undated, untitled, and anonymous bronze sculpture of a crab accompanied by a politically pointed retelling of one of Aesop’s bleakest fables (briefly: crab forsakes the seashore for the new horizons of the meadow, is eaten by a fox, and in its death throes thinks to itself “Serves me right for stepping outside my allotted spot”).

Geography, or at least the mapping of dead end dreams, was suggested by David Adler’s archival presentation of photographs of American prisoners posing against the images of glittering skylines, verdant valleys, and Hockney-esque swimming pools they had painted on their cell walls, while the curdling of language into sloganeering was examined in Mathias Faldbakken’s series of corrupt and almost illegibly corrupted printed slogans from 2008 (“Young Is Better Than Old,” “Rich Is Better Than Poor,” “And Almost Anything Is Better Than Politics”).

History, inescapably, was everywhere, and seemed always to point to the present, whether in the form of nineteenth-century cartoons of an allegorical figure of Greece gluttonously vomiting loans or cowed before Britain, Germany, and France; displays of the cheap casts of classical statues once used in the school’s drawing lessons; junta-era tourist posters; or the flight uniforms designed by Pierre Cardin for national carrier Olympic Airways, sold off by the Greek state in 2009. The show concluded with a monitor showing a YouTube clip of Philippe Petit’s 1974 tightrope walk between the twin towers of the World Trade Center installed next to a window through which one could glimpse the glowing Parthenon. If this is the end, where next? What new future ruins might we build?

The word “urgent” is used too often and too lightly in the contemporary art world, but it feels appropriate to apply it to “Monodrome.” This self-searching, grief-filled, and at times fiercely defiant exhibition did much more than illustrate a crisis, or subject it to glib theorization. Rather, it articulated a dull ache of exhaustion and loss, the throb of bones burdened by too much experience. At a time in which we often ask art to function as a form of journalism or politics, to report the facts or to change them, we should not forget — as the 3rd Athens Biennale demonstrated — how skillfully it might also speak of those deep, precious, and fugitive things, our feelings.