Beirut

Mourina Al Solh / Wael Shawky

Exhibition No. 17 / Contemporary Myths II

Galerie Sfeir-Semler

November 25, 2010–March 19, 2011

It’s hard to imagine the humble toothbrush assuming greater artistic gravitas than it did in the work of Allan Kaprow, who scripted the act of cleaning one’s teeth — half asleep, alone or with a lover — as a performance of profound intimacy, an ordinary act as the art of everyday life. But one of Mounira Al Solh’s uproarious new videos does just that, turning a pair of brand-new toothbrushes in an otherwise empty apartment, soon to be inhabited by her brother and his wife, into a set of ingenious (and hilarious) props. With the heads of those toothbrushes peeping out from behind her ears, the stems jammed into the corners of her collarbone to hold them in place, Solh plays the parts of five comically construed animals in A Double Burger and Two Metamorphoses: A Proposal for a Potential Cat, a Potential Dog, a Potential Donkey, a Potential Goat, and Finally a Potential Camel (2010–ongoing).

The video proceeds in five heavily scripted episodes. Each follows the same formula, with Solh playing herself and the animals as they arrive at her house, one by one, and demand to be fed. Solh, however, has invited them over for a different kind of social interaction. She wants to discuss books she’s been struggling to read — from the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s On the Social Contract to the satirical novel Max Havelaar by the Dutch writer Eduard Douwes Dekker, better known by the pen name Multatuli, about coffee and colonialism in the late nineteenth century. Moreover, she also seeks out some awkwardly intimate exchanges. She asks the cat for a slow dance, the dog for a kiss on the eyes, the goat for a swap of saliva. And yet, all of the animals gruffly turn her down.

Solh reads each piece of dialogue with a white sheet of paper covering her mouth, such that the conversations hinge on her muffled voice and the expressiveness of her heavily made-up eyes. The episodes are spliced with still photographs of Solh improvising her characters with random bits of clothing and household goods — think spandex, construction paper, rolling pins, mounds of flour, face paint, a beaded necklace and a magnifying glass, all outrageously effective means of conveying a lot with very little.

For her first solo exhibition at Galerie Sfeir-Semler in Beirut, A Double Burger and Two Metamorphoses is projected onto the back of a large shipping crate, with another, smaller shipping crate serving as a bench for viewers to sit and watch. The crudeness of the installation amplifies the provisional nature of the piece, which is both the documentation of a bravura performance and a rehearsal for a work that is very much still in progress. (Solh hopes to reshoot it entirely in Arabic, and imagines installing it one day in a room adorned with a series of cuckoo clocks.)

Solh’s show bears the utilitarian title ‘Exhibition No. 17.’ It’s not her seventeenth exhibition to date, mind you, but rather the gallery’s. It’s also Sfeir-Semler’s second experiment with mounting two robust, self-contained shows at once. The first paired Yto Barrada with Etel Adnan, who, though very different, shared so many material affinities and elusive political sensibilities that their parallel exhibitions were rousingly complementary.

Lining up Solh’s ‘Exhibition No. 17’ with Wael Shawky’s ‘Contemporary Myths II’ is, by contrast, a totally schizophrenic affair, to the extent that separate entrances, or an insurmountable barrier between them, might not have been a bad idea. And yet, the experience of drifting back and forth between Solh’s world and Shawky’s, or of hearing the sounds of one artist’s work bleed into the other’s, or of filling your head with Shawky’s delicate drawings while Solh’s are still making impressions on your mind does evoke something of a sensible and generative union.

Both shows are pierced by moments of sudden and rather jarring eroticism, such as the gorgeously weird scene of an adoption ceremony in Shawky’s video Cabaret Crusades: The Horror Show File, when Thoros of Edessa and his wife name Baldwin of Boulogne their son and sole heir. Baldwin drops to his knees, lifts the skirts of his new mom and dad, and them shimmies up into their gowns for a strange little dance with them. (Shawky explodes this suggestion of sex in the following scene, when Baldwin thrusts his spear into his parents, killing them both and claiming their kingdom for the Franks.)

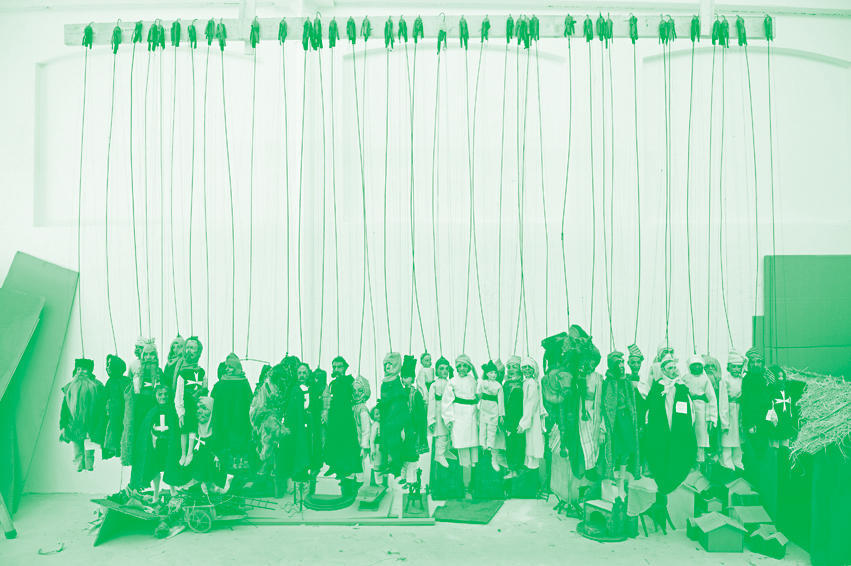

Both shows also deal, albeit very differently, with dress, props, and intense theatricality — through Shawky’s elaborately cinematic production involving two hundred-year-old marionettes from Turin, and Solh’s delightful drag impersonation of the artist Bassam Ramlawi. But what links the two shows most is a subtle, even muted, undercurrent on the relationship between time and drawing, the quick and spontaneous exercises that both artists do as a kind of mental and physical form of calisthenics.

Shawky’s second major work to tackle the history of the crusades, the Cabaret film is by far the artist’s most epic and magisterial piece to date, focusing on a string of events in the eleventh century leading up to the crusaders’ conquest of Jerusalem. The political implications of using marionettes to convey this history are quite clear. The aesthetic power of those puppets, however, is quite a surprise. Their faces are haggard, at times even grotesque, but a series of rather straightforward portraits of each figure set against a white background comes across as deeply haunting and strangely beautiful.

A long glass vitrine filled with the flags and emblems that would have been sewn onto the crusaders’ clothes, but are rendered in sandpaper and tarmac, ties this body of work to Shawky’s early videos and installations, such as Asphalt Quarter (likewise a large, extravagantly detailed yet still somehow dark and subdued diorama of a gunmetal gray castle in Aleppo surrounded by a moat of oil and a landscape of gravel).

And then, set back in a nearly hidden room is a suite of drawings in ink, pencil, and metallic pigments, depicting dreamlike fortresses, dragons, and whales worthy of giving Moby Dick another read. Over on Solh’s side of the gallery, meanwhile, is her own suite of drawings — or rather, those of the fictional Ramlawi. As the story goes, Ramlawi has devoted his life to exploring the work of Otto Dix, Cindy Sherman, and the Dutch painter René Daniels. The son of a Basta juice vendor, constantly stuck in Beirut traffic or subject to the whims of associates who are chronically late, he also doodles away whenever he’s waiting for someone or something, and then layers those drawings with colored vellum.

That Solh — who studied painting at the Lebanese University’s Institute of Fine Arts and took drawing lessons for a year with the inimitable Hussein Madi before heading off to Amsterdam to attend both the Gerrit Rietveld Academie and the Rijksacademie — has invented a character to inhabit, a male artist who paints and draws and works on tactile things, while she, through him, explores what it really means to be an artist. In videos and faux documentaries and keen installations, her work marks a brilliant extension of the themes (gender, identity, the pitfalls of an artistic persona) she previously explored in videos such as The Sea Is a Stereo and As If I Don’t Fit Here.

More than this, ‘Exhibition No. 17’ also wrestles with a whole new constellation of ideas (freedom) and desires (for a second passport, for belonging, for knowledge). Her nineteen-channel video installation titled The Muted Tongue, in which the Croatian artist Sinisa Labrovic acts out nineteen Arabic proverbs, not only relishes the richness of the language and exemplifies Solh’s bawdy, quirky humor; it also shows her as adept at directing performances and embodying them herself. Given that several of the works here are still unfinished or incomplete but hold their own against Shawky’s that are so resolutely polished, it’s a fine indication of good things to come.