Reading the arts coverage in the papers, or doing the rounds of the galleries, it often seems as if all contemporary artwork produced in Britain is the consequence of an evening the artist spent down at the pub with a few mates coming up with outrageous or just plain stupid ideas — then actually making good on them despite the next day’s hangover. The yBas represented the pinnacle of this pub culture iceberg, and some of their work is proof that the results can be truly brilliant.

Post-yBa generation Londoner Mustafa Hulusi seems to abide by this working practice and to prof it from its occasional brilliance. His performance Shouting at the Television (2005), realized with the writer JJ Charlesworth, resulted from one such evening. The work is self-explanatory: Hulusi and Charlesworth provide armchair commentary on the television, which for the most part is as silly and insubstantial as it sounds. However, the feed of media images, which ranged from a documentary on West Point Military Academy to Eastenders, proves a neat counterpart to Hulusi’s other, better-known body of work, a series of large photorealist paintings. (The video documentation of the performance was installed alongside the paintings in ‘The End of the West,’ Hulusi’s 2005 solo exhibition at Max Wigram Gallery, London.)

These reproductions of photographs, taken by Hulusi in Northern Cyprus and blown up billboard-size by a professional illustrator, examine spectacle culture with greater nuance. A girl’s hand — that of the artist’s niece — reaches out to touch a series of indigenous flora: a white lily, an apple and a lemon tree. (Hulusi visits the island frequently, and his practice is increasingly defined by an investigation of his Turkish Cypriot background.) The paintings look bright, vivid, real. However, their lack of obvious promotional subject matter confounds attempts to read them quickly, and their shiny quality elevates them from mere swashbuckling statements on spectacle culture to complex objects in their own right. In a previous series Hulusi made a more blatant comparison by juxtaposing photographs of models lining up to hit the runway with rusting old tankers, as if to suggest that both images carried equivalent meaning, or lack thereof.

Hulusi also creates sculptural versions of his comment on the aesthetics of propaganda and advertising by silkscreening the photographs onto steel. The combination of shiny metal and pixelated image creates a gauze effect that makes the steel look transparent. These “gauzes” are supported by a billboard-like wooden structure — laying bare the propping up of the artifice.

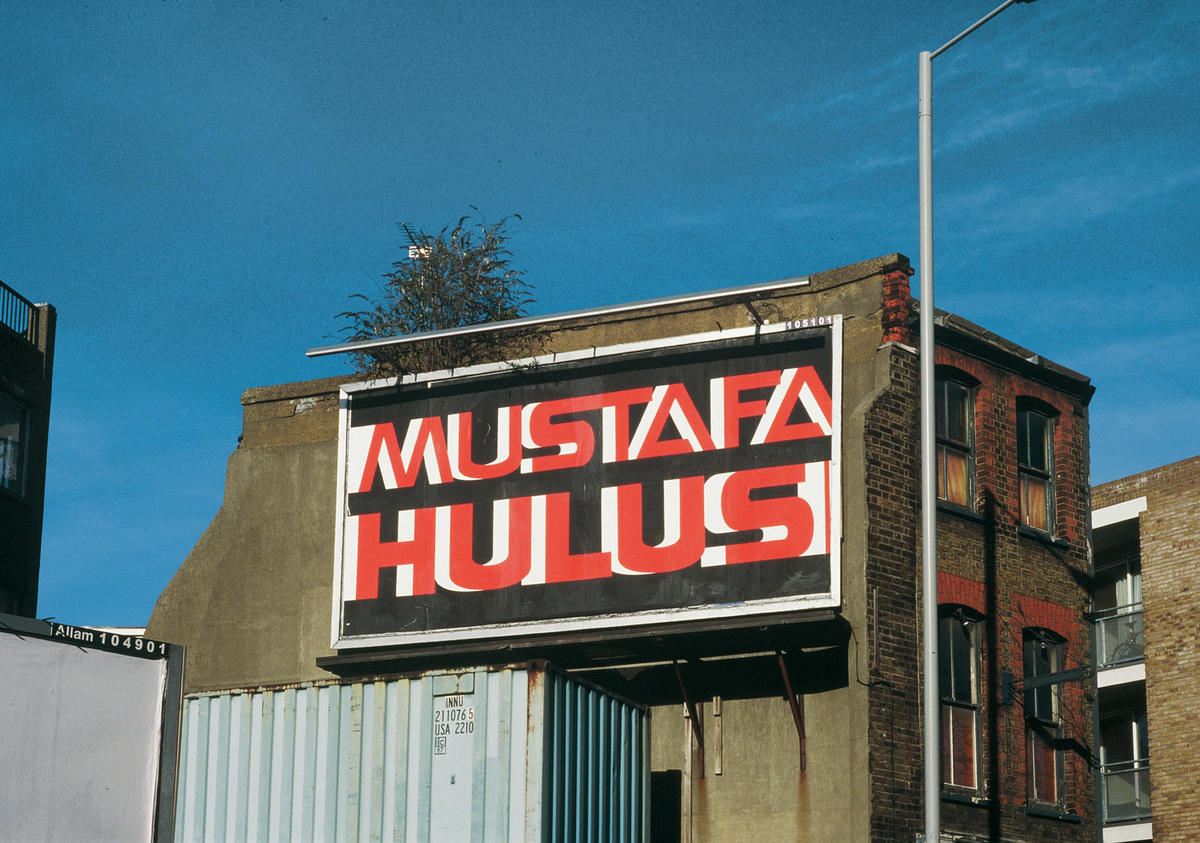

Hulusi worked in (what he terms) “billboard real estate” — buying and selling billboard advertising spaces — after graduating from Goldsmiths in 1995, only resuming his art practice after starting his MA at the Royal College of Art in 2000. He speaks about how advertisers set out to change the way people think about products with palpable admiration, and he mimics their strategies fluently in his own work. However, his goals aren’t always clear, a position that Hulusi would insist is actually intentional: in an ongoing street poster project begun in 2004, he covered the Hackney area of London with billboards bearing his name. The simple block lettering of the design is extremely catchy, and Hulusi’s trained eye for location ensures that the ads look fantastic against gray, sexy Hackney, while his vaguely Middle Eastern name imparts the necessary gravitas.

The lack of instant content in the Hackney project encourages the viewer to fill in the blanks and, according to Hulusi’s press material, “imagine an idealized product.” Hulusi shares a critical engagement with advertising with several artists, including Angus Fairhurst and Shirana Shahbazi. What unites their practices, which seem quite different, is that they don’t use pre-existing images as their source material but instead create their own. Hulusi makes politically charged imagery from his pictures of his niece’s hand; Shahbazi sends her photographs to be writ large on gallery walls by a sign painter; and Fairhurst, whose earlier work consisted of removing the imagery and text from advertisements before installing the resulting collages in lightboxes or straight onto the wall, has recently done away with advertising copy altogether in favor of fabricating his own ads for the lightboxes. This common strategy — if it can even be given such a coherent label — marks a possible step away from appropriation art toward a new critique of spectacle culture that doesn’t depend on abstracting images from their meaning but rather invests them with new meaning.

But to draw more than a tentative comparison might be pushing it: Hulusi himself doesn’t see his work as in dialogue with that of any of his contemporaries. He is, however, deeply involved in the art world in other ways, acting almost as a one-man art impresario: he has curated a number of shows in the UK over the past few years, notable for their inclusion of a vast range of younger artists, at the Royal Academy and the Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art, among other venues. He also works occasionally as an art advisor, and is on the acquisitions committee for the Arts Council England.

Hulusi has come a long way from his excruciating The Mustafa Hulusi Performance (2000), documented in a series of framed photographs with text, in which he went on holiday to Casablanca and slept with eleven prostitutes on eleven consecutive nights. (Hulusi paid each prostitute forty dollars for the night, “a fortnight’s wage for the average factory worker,” which, by insinuating that Hulusi was thereby sparing the prostitute two weeks’ worth of labor, served only to compromise the situation further.) Some ideas are best left in the pub, as Jorg Immendorf showed us in style. Refining his focus from Third World countries in general to Cyprus in particular has tightened Hulusi’s practice. However, he still seems to be casting around dilettanteishly for the right approach, working through art and theory trends in the meantime.

But perhaps art’s interest lies partially in its potential for failure. ‘The End of the West’ was up at the same time as Richard Prince’s exhibition of new personal check/joke paintings and sculptures at Sadie Coles HQ. In terms of technique, bright spark Hulusi could learn a few lessons still from the grandmaster of appropriation, who fuses craft with blinding critique into gorgeous objects that often function independently of their critical message.