White people love Homeland. I am one of them.

I knew he was Iranian the moment he opened his mouth. Dear, dear Abu Nazir, America’s newest jihadi menace. But this ostensibly Arab terrorist was a little different. This one had a son, whom he loved very much. He had a beautiful house, always bathed in pale light; he spoke perfect English and he didn’t have a glass eye or a hand missing and he didn’t cackle maniacally when his underlings tortured their victims. This terrorist had a personality that you couldn’t exactly hate — and we knew exactly why he hated us. (The US had bombed Nazir’s compound in northern Iraq, killing dozens of schoolchildren, including his beloved son.) Most important, this Arab terrorist was loved by an American sergeant. He had charisma — a baddie with a heart of gold. Internal conflict on cable television! And not even on HBO.

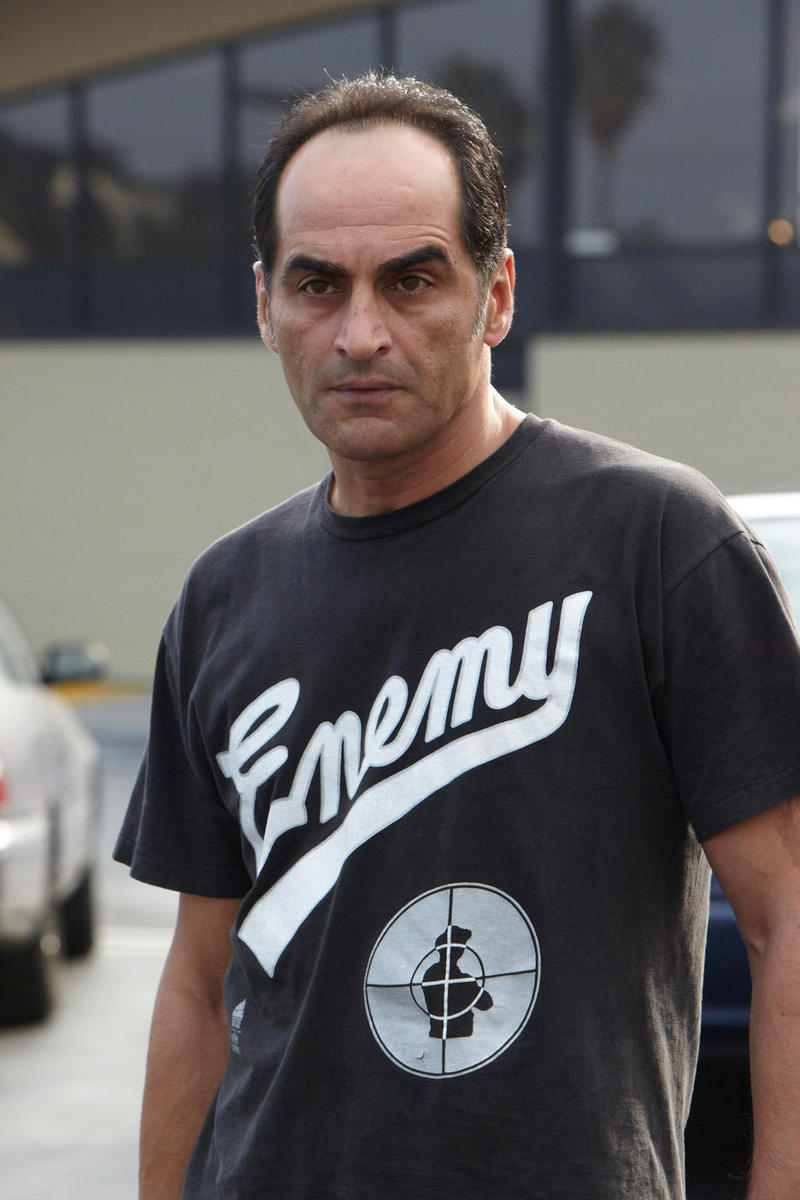

Do white people love Homeland because it’s not so black-and-white? It certainly can’t be because of Carrie Mathison’s (Claire Danes) nonstop cryface. (Look it up.) But when Navid Negahban, the Iranian actor who plays the soft-spoken Abu Nazir, is on the screen, somewhere in the uncomfortable depths of your television-viewing soul, you’re kind of rooting for him, and it is confounding and exciting and definitely different. I don’t think Homeland is the best show on earth. The second season opened in a fictional Beirut so one-dimensional that the Lebanese government thought about suing the producers. (It didn’t help that the episodes were shot in Tel Aviv.) Homeland is a simple show, where the Americans truly believe they are a force for good.

But it is a better show than many, and Negahban has a lot to do with that.

Lisa Farjam: Hi, this is Lisa from Bidoun magazine.

Navid Negahban: Hi, Lisa. How are you?

LF: Fine. How are you?

NN: Very good.

LF: Thank you for taking my call on a weekend.

NN: Thank you.

LF: So I won’t take up too much of your time, I just have a couple of questions. Um… we’re really interested in speaking with you. I’m a huge fan of Homeland and obviously have been watching it from the beginning, and I think that you’ve really taken on the stereotype of the evil jihadist and given him a complexity rarely seen in Hollywood. Abu Nazir has a soul, a backstory, a reasonable explanation for his hatred of America, and I was wondering — first of all, how did you approach the role? Was it all right there in the script?

NN: Okay. The character was created by Alex Gansa and Howard Gordon, but at the first meeting that we had, it was just an idea of the character. I don’t think we had a real sense of what his personality was going to be. And at that meeting, they asked me how I saw Abu Nazir — and my answer was that to me, he is a man who stands up for what he believes in.

LF: Yes.

NN: From his point of view, his actions are just. What I try to do is to portray him from the inside out. Not what he is being seen as, but what he believes he is. And I think that sometimes there is a misunderstanding because we look at people — we start judging them for what we think they are from the outside, without trying to find out what caused them to become who they are. We forget the process.

LF: Yes, of course. I’m sure you’ve had to play that kind of stock Middle Eastern character as well, you know, in some of the roles you’ve taken on in your career. It seems like this is a huge opportunity, and I was wondering if you felt it’s an opportunity not only for yourself but for other Middle Eastern actors to kind of break out of this traditional typecast.

NN: I believe so. But before we go there you need to understand that the team that I’m working with is a very well-educated, very fair… team. The creative team is very open-minded. When you look at their personalities, each of them has had a very colorful life, they have been through ups and downs, and the way that they look at each situation — they don’t see it black-and-white, they always pay attention to that gray area. The gray zone. And I’ve played characters who are very stereotypical villains, kind of a caricature of a villain, and even then I tried to bring something into it. Uh, please don’t misunderstand me, I’m not saying that I’ve achieved my goal.

LF: [Laughs]

NN: But most of the characters I’ve played, even in Brothers, when I played the villain, or even in The Stoning of Soraya M, I was playing Ali, what I tried to bring in is the journey of the character. Because to me it’s very important for the audience to see the process… what’s causing them to become who they are, and if we can understand and acknowledge and recognize that, we might be able to avoid creating these kinds of situations. Do you get what I mean?

LF: Definitely, definitely.

NN: And to be very honest with you, I’ve had friends who don’t want to touch these kinds of roles.

LF: Other Middle Eastern actors?

NN: We’ve had long discussions about it. But I feel that we have a better understanding, coming from that culture and from that mentality, and that if we refuse these parts, then there are going to be actors playing those parts who might not have enough… let’s put it this way, enough understanding of the culture of what these characters are going through, so they’ll come and play them as is written in the script. And sometimes the script doesn’t have, doesn’t give, depth of character. So to me it’s very important — I don’t refuse to play these parts. I like to play these parts, because they are very complex characters that need to be understood.

LF: Well, I think you’re doing an excellent job, and I think it really does add so much to the show. I wonder if part of the success of the show is that people can somehow relate to your character in a way they might not even want to, you know? It’s really fascinating. And I was wondering — have you seen the Israeli original?

NN: Uh, I saw the original… I haven’t seen the whole thing, actually. I saw some of it this year, when we went to Israel to shoot the first few episodes of second season…. Can you give me a second?

LF: Sure.

NN: [Speaking to someone else] Your front tire? You should put air in it. You hit the rim, that’s why you are losing air. And you’re going to get in trouble, especially on these tires. You might have to stop somewhere nobody can help you.

Woman: Where would I get air?

NN: Just go to the gas station and get some air in there. [Back] I’m so sorry, I’m sitting in the parking lot and the car next to me has one of those spare tires, and the lady who was driving the car was not paying attention —

LF: Well, that’s very nice of you. [Laughs]

NN: She’s going to get in trouble.

LF: Helping a fellow Angeleno. [Laughs] Going back to Israel and the original series. I know that, the writers on the original show had interviewed Israeli POWs and I was wondering if you had done any of your own research into how to play this Hizbullah leader.

NN: What I did — they had a fictional bio for the character, and it was two paragraphs: where he was born, where he was coming from, where he went to school. And I took that and went to the Internet and there are lots of similar personalities out there. So I just took that thing and tried to bring my own understanding of what these people are going through and just put it together. I don’t know, it’s a stew, it’s… whatever happens. I’ve said it in other interviews, but it’s true — the character really came to life at the end of first episode in the first season, the moment I had with Damian, that Abu Nazir has with Nicholas —

LF: Where he puts his head on your shoulder?

NN: Yeah, oh my God. That was the birth of Abu Nazir. It was so powerful. I’ve never experienced something like that on a set.

LF: So that wasn’t in the script, that was—

NN: No, it wasn’t. Some of the things that you see happening is — we stay true to the script, but the emotion and the vibe is always being improvised at a given moment. And there were a couple of scenes that we shot in the pilot where they just kept the camera rolling even though we were done with the script, and they ended up using some of those shots in different episodes, because they were so rich and so powerful.

LF: That’s really great. It must be really nice to work on a show with that kind of freedom.

NN: Oh, it’s fantastic. And I think we owe it to Showtime…

LF: Yeah.

NN: Showtime has given us that freedom. And the creators of the show are very open, they’re looking for what’s the best for the show. For the story. There’s no ego there. And that’s what I like — I enjoy working with them.

LF: I wanted to ask you a few questions about season two of Homeland, which begins in Beirut, though it was shot in Tel Aviv. And Homeland portrayed Beirut as a city kind of swarming with militiamen and guns. And I don’t know if you’re aware but the Lebanese tourism minister is considering suing Showtime for defamation. [Chuckles] And I was wondering, first of all, what was it like for you to be in Tel Aviv? But also, what do you make of the Lebanese anger over representing Beirut in that way? Had you, have you, been to Beirut?

NN: I had never been to Beirut, but I’ve worked with lots of Lebanese people — in Jordan, the majority of the crew when I was working on The Stoning of Soraya M, they were from Lebanon. And I’ll say it, they are the craziest party animals I’ve ever seen. [Laughs] There is no sleeping.

LF: I was shocked when I went there. I mean it’s an incredibly bourgeois city, first of all, and they really know how to have a good time.

NN: Yeah, these guys — just imagine, they’re getting up at six o’clock in the morning to go to the set, and they are working until eight, nine o’clock at night, and they’re telling me, “Oh, Navid, you wanna go and grab bite to eat with us?” I said, “Sure.” “Oh, we’re going back, to take a shower, change and go.” I said, “Okay.” And then we go out and all of a sudden it’s three, three-thirty. I said, “Guys, I can’t keep my eyes open.” “Oh, don’t worry, half an hour more! Half an hour more!” We go back and then the next day you have to get up again at six o’clock. I said, “Guys, how can you do this?” And they said, “Oh, you know… every second counts, so you live your life.” And that’s how they were. And to be very honest with you, the way that they described Lebanon to me, and the way that they described their ways to me, I, um, I was very interested to go and see it. I mean, if my schedule would have allowed it…

But I would say first of all, Homeland is a TV show, it’s fictional. And if they want to sue Showtime for that, then the government of France ought to go and sue the producers of Taken.

LF: [Laughs]

NN: Because if you believe that movie, oh my God, Paris is not a safe place. These things happen all over the world. It wasn’t — we didn’t portray Beirut as a dangerous city; it was just a place, like any other place in the world it could have been, that this group of people… they just meet. So it wasn’t about portraying Beirut as a dangerous place. It’s just a TV show.

LF: Right. I think people understand that it’s very rare to be completely one hundred percent true to any kind of geography when you’re filming anything, regardless of budget. But it was more that this was an opportunity for people to see a city that they may know nothing about, or may not feel comfortable visiting because they might have a certain stereotyped idea about what it was like, and this was perpetuating that, you know? So I think it’s —

NN: Yeah, but at the same time, I’m so sorry, but… people are not stupid. The audience is smart, especially the people who are interested in Homeland. They are the sort of people who don’t just accept what they’re being told. So these are not the people who are going to go and judge a — I’m sure that nobody was even thinking about Beirut until that statement came out, because the people that were in the story, they were not in a Beirut story, they were in a Homeland story.

LF: I wanted to ask you about your background, too. You grew up in Mashhad, right? And your parents remained in Iran during the revolution and the rise of Khomeini. I was wondering how much you remember from that time, and how did your life change?

NN: I left in 1985, during the war between Iran and Iraq, and there are, um… there are incidents that I try not to even remember. I try to forget. There are things I have seen that… had a huge impact in the way that I am looking at the world and looking at life, at my life and other people’s lives. And, I remember, during the war between Iran and Iraq, we didn’t have, uh — you’re Persian, aren’t you?

LF: Yes.

NN: So you’ll remember that all the soldiers, of course, they went to war.

LF: Yes.

NN: And then after the soldiers, the police officers went. So we didn’t have enough adult males around. [Laughter] And then they went to high schools, and they were saying to all the high school kids, especially the older ones, “If you guys want, you can go and spend six months in the war zone, go to the front line. Or you can serve as a police officer in the city, and that will help you to get into the university.” You can do this, you can do that. And lots of guys… I have friends, who went. They went to the front, they come back to school… or they don’t come back, and there’s a red tulip sitting in the chair next to you, and you know that the person is not coming back. I mean, you know what the red tulip represents, right?

LF: I do, I do. I remember my cousins telling me about the tulip…

NN: Yeah, the bullet wound. And so for me going through that, it, uh… it kinda… my teenage years were filled with… being an adult. Kind of, being there to comfort people, to protect people, to take care of the younger ones. So that was a huge, um… I mean, now that we’re talking about it, I’m remembering friends who went and never came back, people on the street who got hurt — the incident that happened at the prison in Mashhad, the things that were happening in the city. It was a crazy time.

LF: I mean, were your parents trying to leave all that time? Or were they committed to staying for a specific reason? Or did they just want to stay, period?

NN: I was a black sheep, actually. I was the only one who left, and one of the reasons I left was that I’d wanted to be an actor since I was a kid. That was my dream. And I just left and I went to pursue that.

LF: What was your TV and movie universe like in Iran? Were you able to watch American things at home?

NN: Oh yeah, in Iran we had lots of TV shows. I mean… I used to build all kinds of gadgets, make holes in the heel of my shoe, for spurs, so I could be James West [laughs].

LF: Wait, who?

NN: James West! From the show Wild Wild West. He was played by Robert Conrad. I always wanted to be a cowboy.

LF: I mean, I remember all of that was completely available before the revolution, but then after the Islamic Republic things did really change in terms of what entertainment was available. And I remember going to Tehran in the 1990s and there being just absolutely nothing available to watch.

NN: Yeah, I mean, I remember if any of the kids got their hands on any movie, then oh my gosh, that weekend was a weekend that we all would get together, sit, and that’s it. It was difficult, but right now those kids in Iran, on the Internet! I went back around 2005 and one of my friends had his computer set with the firewall and this and that, and we are sitting there and all of a sudden I see that on his TV, there’s over four hundred and something channels. All these movies, and I said, “Geez, I don’t have this in America, I should come back to Iran and live here.”

LF: [Laughs] Have you received much criticism, here or there or anywhere, for the roles you’ve taken?

NN: Some. After I did The Stoning of Soraya M, one magazine said that I was making movies against Iran and Islam. Which was just wrong. To me, when I did The Stoning of Soraya M — this is very important, this is something that people should understand — I didn’t make movies against Islam, and I didn’t make movies against Iran. I made movies portraying people who are abusing Islamic laws to take advantage of people.

LF: Yes, there’s a difference between making a movie against Islam and making a movie against fanaticism, you know? I mean…

NN: And that was very important for me. I’m pure Iranian, but there were people in the media here and there who attacked me: “Why would you make movies like this? Why would you be part of that? You’re giving Iran a bad name.” I disagree. The thing is, we have lived our lives by sweeping the dirt under the carpet, and as long as we do that, the dirt is going to stay there. Everybody who says, “Oh no, everything is — no problem.” I mean, as long as we’re not honest with ourselves, as long as we keep lying to ourselves that everything is good? Everything gonna stay there, nothing gonna change. So we are responsible. We need to, each of us, we need to stand up and take responsibility and clean up. Say: okay, you know what? I made this mistake, this is my fault. I did this. I’m willing to say that was my mistake, let’s fix it. Let’s make it better. And that’s the reason why I made that movie.

LF: That’s great. Thank you for talking about that.

NN: No, thank you. It’s just, to me, I think… the first step that we need for a better world, to have a better world, is to be honest. To be sincere and honest and stop… painting a donkey and selling it as a zebra. [Laughter] A donkey is a donkey, let’s accept that it’s a donkey. So what we need to do is we need to be honest and fair and respectful toward what people believe. I mean, I truly believe that everybody’s free to do whatever they want to do as long as their freedom doesn’t take it out on someone else’s freedom. So, not everybody has to dress like me, not everybody has to think alike — they can do whatever they want to as long as they don’t dictate to me what I should be wearing and what I should be thinking.

LF: Right. Which isn’t always —

NN: Am I talking too much? [Both laugh]

LF: Of course not.

NN: Oh, you’re gonna get me in trouble!

LF: Did you see Argo? What did you think?

NN: I saw Argo. I loved it. I remember those days. It was so — I take my hat off for him, he did a fantastic job. It was so well done. Very well done.

LF: I was just so excited to finally see a movie with, first of all, actual Persian actors who spoke Farsi. Hopefully there will be more movies like it.

NN: We’re working on it.

LF: [Laughs] Good.

NN: No, I’m serious. This is something that is very, very important to me. There are movies being made, and we say that these movies are not portraying us in a good light, okay? The reason that they’re not good for us is because these movies are being made by a group of people who want to put themselves in the spotlight. They’re telling the story from their point of view, and their point of view is very accurate and respected. That’s how they feel, and that’s how they think, okay? So if we really want to go and criticize them for speaking their own mind…? What we need to do is, we need to tell our side of the story. Say: that’s fine, that’s great, it’s a beautiful movie, it’s a beautiful story, it’s from your point of view. Okay, now this is my point of view. Then we’ll let the audience judge for themselves which one is which.

One of the things that’s happening, especially with our community — I’m so sorry to say it, I know I’m going to get myself in trouble by saying this, but — I could never keep my mouth shut — but — jeez, you’re gonna get me in trouble — but the thing that is happening with our community is that our voice is louder than our actions. We preach, we go, we talk, and when it comes to action… umm, I’m not sure. I mean there are projects, I know people who they have wonderful scripts, beautiful scripts, Iranian writers, fantastic scripts, and they are coming and they want to tell the story, they want to introduce the other side, they want to introduce us. But nobody, nobody supports them. And then we have very powerful Iranian people who are investing in movies that have a big name, and they think that, okay, that is the way I’m going into the film industry.

LF: Right, because it’s a guaranteed success. Whereas taking a risk — I mean, they don’t know where it’s gonna go.

NN: Yeah. The risk, we need to take the risk if we want to say something. As long as we play it safe, there’s no way it’s going to work. If I wanted to play safe, I wouldn’t be here. I’d never have gotten here. There were… my gosh, the first six months I was in Los Angeles, I was sleeping in my car. I still have the — there’s a shower curtain and a rod, I used to hang that in my car, my old car. I used to hang that in there, and I would hang the curtain on it, and I would sleep in the car, and I still have that curtain and that rod, I still have them in my current car. And every time that I turn around and I look at it, I remember those days, and that’s how I keep my feet on the ground. I say, okay, this is who I am. Don’t let the drama and the success distract from where you want to go. Someone asked me, “How does it feel now that you’re famous? Now that people might recognize you. How does it feel?” I said, “Well, I’m still the same guy. Nothing has changed.” To be very honest with you, it hasn’t changed me. I’m still the same person. I’m still driving the same car as nine years ago. I love my truck—

LF: And that’s just harder in LA, to maintain that. Because it’s very easy to get swept up.

NN: It is. One of the keys to success, in my opinion, is never allow Hollywood to digest you. If you are the one who is digesting Hollywood… you will be successful. It doesn’t matter where you are in your career. At the moment that you let the industry tell you who you are — that’s when you’ve lost yourself. It doesn’t matter where you are in your career, from then on you are just a puppet. So that’s tough. That is… I don’t know. I’ve always been a dreamer, so —

LF: [Laughs] It’s really heartening, and thank you.

NN: You are very welcome. Honestly, one day we were — we just had to shout out to all the Iranian people. There are so many powerful, and there are so many successful Iranian people here, and I don’t know, I feel that we just need to… to come out of the closet. We’re hiding ourselves because we want to blend in. Why? What makes us who we are is that we are different. We are part of this society, but we have our own color. We are part of this society, but we have our own sensibilities. And our sensibilities are what really makes us who are.

LF: Well this was the original impetus of Bidoun, you know, to offer another look, another perspective, at the Middle Eastern community. Something that hadn’t necessarily been seen that often. Not enough, anyway. And so —

NN: Really, Lisa, I think that society is ready. America is ready. They are hungry — hungry to be educated, hungry to be introduced. What we need to do is, we need to get together and say okay, I’m going to take a chance. I’m going to take a risk, let’s go. Let’s do it. Let’s tell our stories, let’s tell these stories and show who we are, instead of trying to copy or mimic the stories that have been done so many times. Let us tell our stories.

LF: Navid, you’re really doing an excellent job and I really appreciate you taking the time to speak with us. I’m really enjoying the show. I think you’re really adding a lot to it. I just wanted to say thank you.

LF: Thanks a lot. Thank you so much. Thanks for talking to me.

LF: Sure.

NN: I appreciate it. And hopefully… hopefully we’re gonna be able to tell those stories.

LF: I hope so. Merci.

NN: Khahesh mikonam. Thank you so much. Khodahafez azizam. Bye.

LF: Bye.