New York

Nina Katchadourian: Enrichment

Sara Meltzer Gallery

November 17–December 22, 2007

Nina Katchadourian’s Zoo made itself heard long before it could be seen. A balloon vendor greeted visitors at the entrance to the multichannel video installation, in a video that showed the frazzled zoo employee amid a bobbing mountain of mute parrots and grinning tigers. An alarming cacophony issued from the gallery beyond: bleating sheep, squawking birds, braying-and-cacklingtype noises of indeterminate origin, screaming children, and what just might have been a merry-go-round.

Inside the immersive environment of screens, projections, and noise, an appropriately zoolike chaos reigned (minus the smells). Ambient noise bounced through the space; none of the sound tracks to the fourteen videos matched the visuals. Sound and image fell into strange pairings, as with the pulsating jellyfish bleating in their aquarium. A giraffe observed the proceedings impassively; headless polar bears floated in a murky blue haze. ‘Enrichment,’ the title of Katchadourian’s exhibition, referred to the human tactics meant to stimulate animals — by setting up challenging “natural” environments, for example, to draw them out of the lethargy of their caged lives. As a representation and evocation of various manmade environments, Zoo hinted at the humor, pathos, and banal realities of animal life under surveillance.

Katchadourian spared us the sight of whip-wielding lion tamers or performing dolphins — the ethos of “enrichment” is all about a happy, healthy, and abuse-free experience of captivity. But Katchadourian’s camera sought out the darker edges of that cheery facade. A video zoomed in on a sign describing a creature that remained hidden from view: “What is that bear doing? You may have noticed that the female Sloth Bear sometimes displays a strange ‘rocking’ behavior. She acquired this habit before she came to the London zoo, probably because her previous enclosure lacked opportunities for stimulating activity.” The reader was assured that everything was being done to “cure her of this habit.” As one imagined the lone bear rocking in a corner, it was tempting to read the work metaphorically, to find echoes of an increasingly controlled society within that microcosm of manufactured “enrichment.”

In the upstairs gallery, Fugitive extended the theme by inverting the immersive formal organization of Zoo and arranging a circle of TV sets around a column. An orangutan silhouetted against a dull gray sky swung from one screen to the next. As it reached the side of one monitor, the next monitor flashed on, pulling the viewer with the animal on its endless trajectory. The only sound track was a low static hum. Here enrichment and stimulation met their opposite: the dull monotony of captivity, tracked in the orangutan’s circular path.

Did ‘Enrichment’ offer any insights unavailable at your typical menagerie, be it gallery space or wildlife preserve? The answer lay in the experience of encountering the work, and its chaotic yet oblique demands on the viewer’s attention. Katchadourian evaded simplistic social critique by scrambling her coordinates; her Zoo was less an observation station than an entry point into a multiplicity of views. Most demonstrations involving other species are intended to drive home well-meaning anthropological points. ‘Enrichment’ evaded such a functional role: the approach was too scattered to instruct, and the deadpan humor defused the critique.

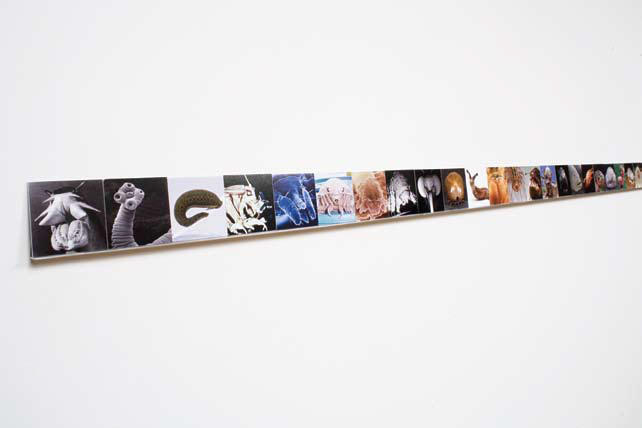

Continuum of Cute, across the gallery, was a small shelf supporting a stretch of wallet-size animal snapshots arranged according to their degree of cuteness, ranging from scaly insects to furry round things, with some bizarre, unidentifiable creatures in between. Continuum restaged the “cute” phenomenon — itself a vast continuum, spanning Hello Kitty culture and PETA marketing campaigns, both of which capitalize on the human instinct to cuddle, protect, and own animals — but remained within the bounds of its two-dimensional appeal, never hinting at the serious mechanisms at work beneath the winning facade.

Within her consistently eclectic body of work, Katchadourian’s observations, interventions, and collaborations transform the everyday in a pointedly modest manner, often risking their own relevance and communicability to pursue personal concerns. Past works have seen her “mending” spiderwebs, “translating” the sound of popping corn by reading it as Morse code, and persuading office workers to communicate in semaphore with random observers looking through a telescope on the street (her recent public project Office Semaphore reprised on the gallery’s terrace, having lost some of its quality of random surprise within the rarified confines of Chelsea). Using strategies inherited from Duchamp and Cage via her teacher, Allan Kaprow, Katchadourian reframes elements of the found environment, both visual and aural, and opens them up to a heightened form of alertness.

If the animal balloons at Zoo’s entrance were overblown stereotypes that said more about representation than reality, the videos within were an attempt to get past that, to create a space of unexpected possibilities, a means to arrive at something more genuinely interesting. In the end, Katchadourian succeeded in communicating a rare curiosity about the workings of the world. Her sensibility rendered familiar situations strange enough to invite reconsideration, setting the stage for new forms of encounter, perception, and interaction.