Notes On a Century: Reflections of a Middle East Historian

By Bernard Lewis with Buntzie Ellis Churchill

Viking, 2012

There are a few things that Bernard Lewis wants you to know. First, he is proud not only of being a historian of record, but an uncommonly prolific one who launched the first modern Middle East history course in a British university back in 1938. Second, he laments the current state of Middle Eastern studies and academia more generally, and in particular has it out for the lasting influence of the late Edward Said, whom he considers nothing short of an intellectual fraud. Third, he knows a lot of rich and powerful people and has had his picture taken with a number of them. Fourth, don’t call him “Bernie” — although he’ll tolerate, just, the American pronunciation “Ber-naaard,” even if he prefers the British “Behr-nerd.” Fifth, his backing of the 2003 invasion of Iraq is much exaggerated. He always thought the real threat was Iran, and told Dick Cheney just as much.

Let us cut to the chase. Bernard Lewis is a founding father of the field of Middle Eastern Studies and has written some of the best-selling popular histories of the region — used variously in the academy, the policy world, and lay circles alike. His reputation as a historian of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish republic, in particular, is noteworthy. Lewis’s scholarship is based in good part on reading source materials in the original language. He has learned Turkish (both modern and the Ottoman-era version) Arabic and Hebrew, as well as at least five European languages, and spent considerable time in musty archives in Europe and the Middle East. In doing so, he has brought rare historical texts to new publics, often translating them from their originals into a trademark Lewisian limpid, succinct prose. And he has at least one book, The Emergence of Modern Turkey, that is considered a classic.

Alongside these formidable accomplishments, there is a Bernard Lewis who is reviled by leftish academia and who is surrounded by dubious sycophants, many of whom are rabidly pro-Israel intellectuals (Martin Kramer and Daniel Pipes chief among them) who use his writings to go much further than he has in bashing the pensée unique of contemporary Middle Eastern Studies. Lewis has served as an intellectual lapdog in the Bush administration’s war in Iraq, lent his name to a right-wing attack on Middle East academia, and has published best-selling books on the Middle East and Islam with frustratingly fey titles such as What Went Wrong? His writings have been invoked repeatedly in post-9/11 debates on the Middle East, and even used to take up the vexed question of “What is to be done?” Lewis has extended his reach to the shores of Europe as well, vocalizing fears about Muslim immigration and the terrifying possibility of a Muslim majority emerging there.

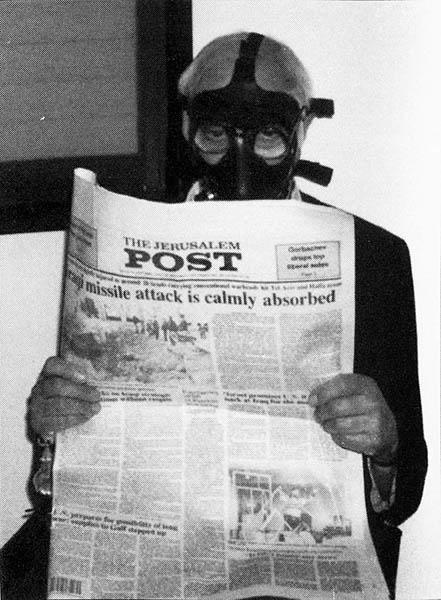

In Notes On A Century, Lewis offers vignettes from a long, and in many respects, fascinating life and reflections on issues close to his heart. It is highly readable, though one might shy away from calling it well-written — perhaps because at the age of ninety-five Lewis likely did not write it entirely himself. (The name of his partner, Buntzie Ellis Churchill, also graces the cover.) Its structure, fragmented into a series of reminiscences, sometimes feel like a painfully long evening spent politely listening to an old professor’s sherry-lubricated ramblings. However there are, it should be said, some great moments, on his life (he served as an intelligence officer during World War II), on his various encounters, and on his worldview — whether one agrees with him or not.

Lewis takes pride in being a teacher as well as a writer, yet his accounts of his former students, particularly those from the Middle East, are at times bewildering. An Iraqi student, afraid of what would await him back home after he lost his scholarship, shoots himself. A young woman with a promising career ahead of her leaves university because she gets married (which, strangely, prompts Lewis to declare himself a feminist). And there’s the time the nephew of the Mufti of Jerusalem, having escaped Britain to join his uncle at Hitler’s side, comes back to swap war stories with his old professor. There’s also a colorful anecdote about how, a day before meeting the Shah of Iran, he intervenes to save the ruler’s granddaughter — a girl who “regarded her courses as something to be fitted into her program of social engagements” — from being kicked out of Princeton, the seat of his own kingly throne for some decades.

And then there is Edward Said. A whole chapter is devoted to his distaste for the late Palestinian scholar. In “Orientalism and the Cult of Right Thinking,” Lewis writes of “a current school of thought which says that history can only be written by insiders.” He calls this “intellectual protectionism,” and laments, more or less rightly, that the term “Orientalist” was “abandoned by its practitioners as obsolete and inaccurate, was scavenged by Said and others and recycled as a term of abuse.” The entirety of the book is peppered with bitter allusions and grumblings about “academic fads” and “new schools of epistemology.”

Whereas others have legitimately seen in Said’s work an overreach by a man outside of his element (Said was a professor of English literature, not Middle Eastern historiography, and has been convincingly shown by the likes of Robert Irwin to be highly selective in his takedown of European Orientalists), Lewis has made Said his personal bugbear. But — perhaps because he was specifically highlighted in Said’s Orientalism as a peddler of bias, generalizations and prejudice — he is tiresomely conspiratorial about Said’s long shadow. “The Saidians now control appointments, promotions, publications, and even book reviews with a degree of enforcement unknown in Western universities since the eighteenth century,” Lewis warns. He goes on to mention that he accepted the chairmanship of the Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa (ASMEA) in 2007 to escape the “straightjackets” of the Middle East Studies Association (MESA) and its “currently enforced orthodoxy.” ASMEA has thus far largely attracted conservative scholars, many of whom, like Lewis, have been passionate supporters of the Bush administration’s Middle East policy.

Perhaps the most dishonest aspect of Lewis’ memoirs is that he is never quite straightforward when it comes to his conservative views. The Lewisian view is one that holds the West and its achievements in high regard, minimizes its crimes (at one point, he dismisses complaints of British imperialism in India by comparing it, favorably of course, to German imperialism under Hitler and concluding it was not so bad!), and perceives dishonesty in Muslim and Arab approaches to the West. He is also silent when it comes to his own well-documented Zionism, refraining from commenting on the creation of the state of Israel, but making it plain that he had close ties with and admiration for Israeli leaders such as Golda Meir, Moshe Dayan, and Teddy Kollek. While he is candid about his assimilated British Judaism and has many interesting reflections on anti-Semitism (notably its pervasiveness in 1960s America), the question of Israel is barely raised save to say that it made his initial area of academic focus, the Arab world, largely off-limits to him as a Jew (hence the subsequent focus on Turkey).

Speaking of political correctness, Lewis will not be accused of it when he writes of the historian’s need for distance as well as empathy for the cultures he studies. After a barb aimed at the Saidians — “at the present time it is more fashionable to assume that everything Western is bad” — he makes a startling case for the superiority of Western empathy. “I will make what may appear to be a blatantly chauvinistic statement and say that this capacity for empathy, vicariously experiencing the feelings of others, is a peculiar Western feature.” The irony here is that particularly in the last decade, Lewis has been especially prone to making sweeping statements about the Muslim world or Arab culture that are founded on the primacy of grand, but ultimately marginal Muslim historical narratives found in dusty texts and in revanchist statements by the likes of Osama bin Laden. Lewis is also prone to routinely trotting out popular, but stale, clichés, such as ones related to how young Arab men’s sexual frustrations might lead them to become suicide bombers (so that they may have access to the seventy-two virgins offered in paradise). Or the notion that the leaders of the Islamic Republic of Iran will not answer to normal deterrence strategies because they “seem to be preparing for a final apocalyptic battle between the forces of God [themselves] and of the Devil [the Great Satan — the United States].” It is frightening to think that this last sentence, reproduced in the book, is lifted directly from emails Lewis exchanged with National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley in 2006.

All of which is to say, in the current American moment, Lewis remains a dangerous man. Here and in other writings, he articulates a view of “Islam” and “the West” as locked in a clash of civilizations. He also propagates the idea of an Arab rejection of modernity that shows little awareness of — never mind empathy with — ordinary Muslim peoples today. And when it deals with scholarly matters, Notes on a Century is painfully out of date with more recent intellectual production from the region (such as his assertion that slavery in Muslim lands is not an object of academic study there). He is made all the more dangerous by the pretense that his choice of friends in politics — Richard Perle, Dick Cheney, various Jordanian royals — is innocent and that his proximity to power is incidental and accidental. The selection of pictures that accompany the book ends with two snapshots that shed inevitable light into just how much Lewis enjoys his status as the conservative establishment’s favored scholar of the Middle East: one shows him in conversation with Cheney (whom he defends as the subject of “willful vilification” by the liberal media), and another, featuring he and his wife in a picturesque Idaho setting, is captioned, blandly, as from “an annual retreat for Hollywood moguls and Wall Street tycoons.” Nice one, Bernie.