Dr H is a sexologist specializing in fetishism and neo-sexuality. In recent years, he has done extensive studies of objectum-sexuality, or objectophilia, in which the attraction to particular objects completely displaces the desire for romantic relations with other people.

Here, Dr H considers the origins and significance of this phenomenon, reflecting on interviews with objectophiliacs, self-identifying and otherwise, across the world.

The increasingly common occurrence of objectophilia is most often attributed to the decline in human intimacy: people isolate themselves from others in favor of communion with their desired objects. Objectophilia is not to be confused with mere fetishism, in which the subject’s relation to a class of object — wigs or diapers, stockings or shoes — becomes eroticized. In any case, such behavior is becoming socially acceptable, as the injection of libidinal value into the world of objects is increasingly seen as a fundamental characteristic of our age.

The original love-object is, of course, the mother. Upon separation from the mother, one begins to seek out the ideal other to incorporate into one’s self—this is the immature object-love of the narcissistic self. As children develop, they learn to accept their failings as well as those of others. They learn to perceive themselves as human and direct their love toward other imperfect humans, identifying with them. In love, the self is ceded; another self overwhelms it.

When this process of psychological maturation fails to occur or is not completed, when the conditions for identification are not met, when the adolescent stage is prolonged in perpetuity, a person might direct his or her love toward things that have no failings or imperfections: ideal objects.

The subject here is not concerned with reciprocity, so the object need not exhibit consciousness. Thomas Mann wrote, “He who loves the more is the inferior and must suffer.” In objectum-love, this is not so; the subject stipulates the terms of interaction and controls the environment, extinguishing the possibility for such suffering. The object will never want to “just be friends.” Conversely, the subject is rarely ambivalent as to the object of his or her desire; most objectophiliacs describe their objects as spouses, and infidelity seems to be rare.

But what to make of objectumlove beyond this narrow observation? Is it the result of increasing asexual tendencies? The hyperliberalization of social mores? Or is it simply the logic, made suddenly visible, of a consumer culture so advanced that objects are no longer fetishized for their supernatural powers, but loved for their mundane qualities?

It remains uncertain. More research needs to be done. One thing is clear: we are witnessing a breakdown of the apartheid between people and things, which will have consequences for both sides. Remember the broomsticks of Fantasia, which quit the dust-covered floors, refusing to submit any longer to the oppressive regime of utility. Then as now, the objects have become the protagonists of our story; or, we now tell their story. Perhaps it is not the human who is in crisis, but the object. As Rainer Maria Rilke noted, “Relations of men and things have created confusion in the latter.”

The Rocket man: m, Libya, 2003 Colonel Muammar al-Qaddafi announced his design for the Jamahiriya Rocket in 1999, to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of his rise to power. (Jamahiriya, Qaddafi’s own coinage, evokes “the nation/state of the masses.”) A few years later I found myself in Tripoli visiting an acquaintance who works at Al-Fateh University. It was not a work trip, but after my friend, a folklorist, told me the story of M, I was determined to investigate. Luckily, she knew where to find him, having employed his services as a mechanic in the past, and offered to come along and serve as translator.

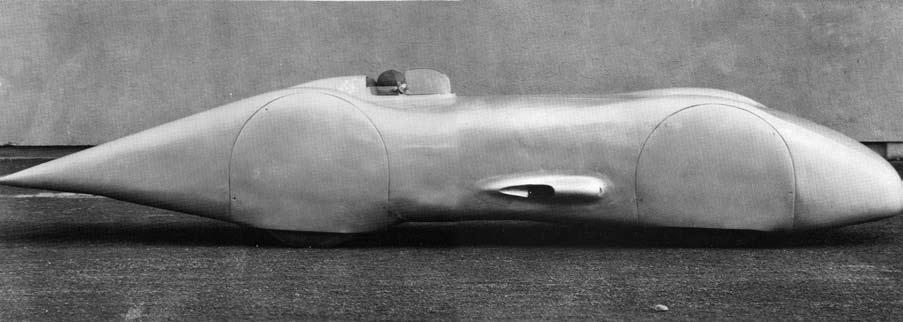

M worked in a body shop in the suburbs east of the city and had fallen in love with the Jamahiriya Rocket. He was tentative when I first approached, but when I explained to him that I simply wanted to know more about his beloved and knew many others who loved similar objects, he became cross. “There is no object like this one,” he said. He took a deep breath, then invited us to sit with him for tea in the garage. “I heard on the radio it would be the safest car on earth,” he recounted, “that the leader himself had said we must have the air bags, the built-in electronic defense system, the collapsible bumper. Most of the cars here are junk,” he complained, surveying the rusted skeletons strewn about the shop’s yard. “The cars I normally work on, they are scraps of metal hung like a gypsy tent over an engine that burns you alive when your brakes fail, and they usually do.”

During the years after sanctions were imposed, Qaddafi announced he had been “thinking of ways to preserve human life all over the world.” The “State of the Masses” car reflected his desire to make rockets for the safety and well-being of ordinary Libyans, while other countries continued making rockets to kill. But for whatever reason, the cars never went into full production. M had obtained his, a prototype, out of luck and conniving. “There is a government official who comes to me to fix his car,” he recalled. “One day he is waiting here with the car. It is the most beautiful and powerful thing I have ever seen—a thing that challenges you, makes you powerless.” According to the official, the Rocket looked like “a James Bond car.” M disagreed. “I told him the leader would not design a car to look like a British killer of our Soviet allies. To me the car looks a little like Nancy Ajram — but she is Lebanese, and this car is more Libyan, with that metallic green color, the front and back looking like a very nice rocket or spaceship.”

The official needed a full inspection of the vehicle, and M obliged. Once he had inspected it, though, he vowed never to part with it. “I just felt the contours, put my hand on the steering wheel, examined the chassis, looked under the hood—I knew I was in love. I know what a beautiful car looks like, and how it performs. But this wasn’t just beauty, it was perfection.”

When the official returned for the Rocket, M stalled. “I told him there was something wrong with the exhaust system and that I had to wait for a part,” he recalls. “We cursed the engineers together.” The official came back again, but the car still wasn’t done. “Then there was a miracle,” M says. The man disappeared. Another customer told M that the official had been taken away for saying bad things about the leader’s car. M expressed regret at the man’s misfortune. But he and the Jamahiriya Rocket have been together ever since, and he is happier than he has ever been. Once a year, on their anniversary, he takes the Rocket out for a ride. But mostly he keeps her under wraps in his garage, obsessively fine-tuning her components, safe from prying, covetous eyes.

Sexual Concrete: A, Israel and the Occupied Territories, 2007 Animism is the fundamental condition of objectum-sexuality. As A put it, when I met her near the West Bank town of Bethlehem, “I look at things as living beings, like you or me. And how are they different? I can communicate with them like with people. For me, this is normal. My partner is a wall.”

The border wall, or separation barrier, or racial segregation wall, or security fence — by whatever name, it has symbolized occupation and oppression and the flouting of international law to many people since it was built in 2002. But not to A. “I am not interested in politics,” she asserts. “The wall is my spouse.” These days she keeps an eye on her beloved with the aid of Google Maps, but she still visits the wall at least once a week, leaving flowers and dates at its base, even reciting poetry. The soldiers look down on her, but she seems not to mind their disparaging remarks. When I ask her why they find it strange, however, she shudders indignantly. “Who says that man is the Crown of Creation?” she spits. “We share this planet with other beings. We all have the same worth, no matter what we are — animal, human, plant, or poured concrete.”

She is not quite sure why she loves the wall, and seems to find such a question preposterous. “What attracts me physically is that the wall is rectangular, has parallel lines,” she admits. “But other walls have those. Why do I love this wall in particular? I cannot put it into words — there are no words. Why do you love your wife? Your child? What reason can you have? One can only tell stories.”

I mention to her that there exists in the literature a story of a man in Silesia who became enamored of the gallows near his home, not because of its grim purpose, but because of its singular geometric form. She nods. “He was not interested in executions, and I am not interested in divisions. The purpose of the object is beside the point. It is the essence we are after.”

The Bibliophile: K, London, 2005

An acquaintance of mine, an English gentleman with excellent connections among dealers in antiquarian maps, prints, and books, sent word that a rare tome bound in human skin had recently been sold at auction to a previously unknown collector. He had seen her after the auction, caressing the book’s mottled cover and inhaling its perfume, and thought of me. He had done a little digging and was able to provide me with her name and address. The next time I came to London, I wrote ahead to K, circumspectly inquiring whether I might talk to her about the book.

As it happened, she was eager to be interviewed. She had always been a bibliophile, she said; her father had been a minister, and in the family home the books had had the run of the place. But she had only become a bona fide objectophiliac recently — at the auction house where my acquaintance had noticed her.

“It was the smell,” she said. Before the bidding had begun she had examined the items for sale, and had been stopped short by “the scent of that volume, the bouquet of ancient pages pressed together by human leather.” She looked slightly flushed, explaining that new books have the smell of pulverized organic matter, paste, and infant ink, while old books, so long as they are carefully preserved, develop their own distinctive odors. “Being in that auction house, I felt like I was in a master vintner’s cellar or the library of a medieval monastery. My excitement was overwhelming. I bid in a sort of blind frenzy, and nearly fainted from pleasure when I won it.” The final price was five figures.

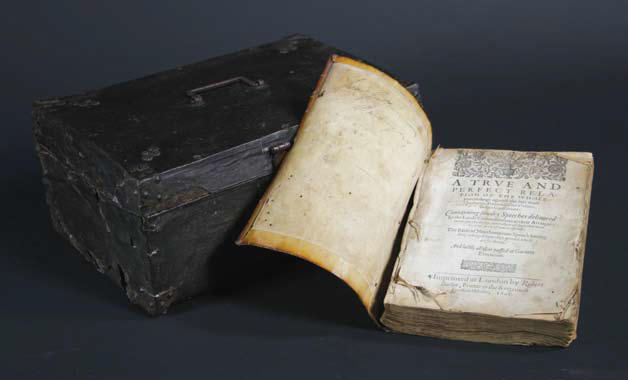

The book is an early seventeenth-century edition of A True and Perfect Relation of the Whole Proceedings Against the Late Most Barbarous Traitors, Garnet a Jesuit and His Confederates. It chronicles the trial of Father Henry Garnet, who was tried and hanged for his alleged role in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, a Catholic plot to kill King James I by exploding the British Parliament building. It is bound with Garnet’s skin and is one of the finest examples of early modern anthropodermic bibliopegy. On the book’s cover, the creased skin bears an uncanny resemblance to Garnet’s bearded face, frozen in an expression of open-mouthed grief.

I wondered whether Garnet’s story was part of the attraction; or whether his having been a priest, and a Catholic one at that, posed any difficulties for a daughter of the Church of England. She laughed at the thought. “The man, Garnet, is simply the occasion for the book. It’s the book that I love.” She whispers that she takes it to bed with her each night, holding it in her arms, enjoying the subtle aroma of its pages and the astonishingly sensitive surface of its cover.

The Pipeline Lover: X, Lagos, 2006

For this one, I have few words.

During an NGO-funded trip to study the sexual relations of slum dwellers, I drove through a suburb on the outskirts of Lagos that was bisected by an oil pipeline. As we rode past a man wearing a Dallas Cowboys jersey large enough to shelter a small family threw himself in front of our car, asking for a donation to “protect the pipeline.” This was not the first time I had been asked for a “donation” during my visit, but it was the first time the solicitor appeared to be asking without contempt. He seemed desperate but not dangerous, so I asked him to explain himself.

This was perhaps the most extraordinary accident in a lifetime of sexological encounters. The man was a poet — he had studied at Ibadan, but was down on his luck — and the man was in love. “She stretches from Warri to Kaduna to Lagos, voiding herself upon reaching the tankers of the Seven Sisters,” he told me. “Here, Olorun owns the sky, the government owns the land, and the Seven Sisters own whatever lies beneath it.” But the pipeline, this stretch of it in particular, belonged to him.

I asked how long he had been protecting the pipeline, and from whom, or what. “I have loved her since I first laid eyes on her,” he said, “she the pneumatic tube in infancy, skin like virgin silver.” But she is vulnerable, he went on, “beholden to her course, sapping the oil fields in the interior and gurgling their black nectar all the way to the Niger Delta.”

But you can’t protect her yourself, I offered.

“You see that she has not perished,” he replied with bluster. “Though she is now rusted, burned. Everywhere Nigerians are drilling into her, collecting her oil with pails, buckets, Dixie cups. The fires have charred her skin and killed even those whose buckets are still empty.”

I reminded him that Soyinka had explained away these incidents as “reflections of the general social malaise.”

Smiling at me, he held out his hand. “And that, my friend, is what I am protecting her from.” I asked him for his name, an address, something I might use to contact him again, but he demurred, still flashing his toothy grin. “This is where you will find me, never far from my love.”

A few months later the BBC reported that fuel from a vandalized pipeline had ignited in Lagos, killing two hundred people. I wondered about the poet, whether he had been caught in the blast. I pictured him scrambling toward the pool of glossy sediment, protecting his love from the predations of the crowd.