Berlin

Shahram Entekhabi

Play Gallery

March 20–April 21 2004

A man in a gray suit and white shirt stands somewhat remotely at the edge of a weekly market and allows the crowd to push by him. His attention is drawn to one of the passersby who bears a surprising resemblance to him. In a hectic, tense fashion, he begins to pursue the man, which leads him through streets, tunnels, house entranceways — until he arrives at his own doorstep. Has he followed himself?

Shahram Entekhabi quietly watches the video projection i? a work in ten episodes which depicts the everyday life of the protagonist “O,” played by Entekhabi himself. A game of perception and observations of the self. The plot of the video by Shahram Entekhabi is not only reminiscent of the film classic “Film” by Samuel Beckett with Buster Keaton — it can also be understood as a reference to the subject of interpretation from the viewpoint of a migrant.

Entekhabi is one of ten artists with a commissioned work in the exhibition Far Near Distance — Positions of Iranian Artists (Kilid). Concurrently, a solo exhibition of his video work is featured in the Play gallery in Berlin Mitte. Bidoun met the artist in Berlin and spoke with him about his video work i?, the accompanying workshop for young people from Berlin and the exhibition in the House of World Cultures.

Entekhabi belongs to a generation of exile artists that haven’t been back to Iran in 25 years. The 47-year-old projects an air of relaxation and ease. A prominent pair of black glasses dominates his face. His look is perfectly suited to the style of Berlin Mitte. Outwardly political, his artistic work concentrates on themes of the human microcosm. “In the film, I observe myself,” Entekhabi says. “My ‘self’ is separated into two people. One is fully integrated and involved with daily happenings. The other always arrives a bit too late — stands in front of locked doors, gets lost.”

Even if Entekhabi is clearly recognizable as the protagonist “O,” his face is always partially concealed and remains in obscurity. A blade scrapes across O’s face. One can hear the breathing, the water and the scratch of the sharp edge. Despite being shot in close-up, the viewer is held at a distance.

“I am interested in exactly that moment in which you are at one with yourself; when you have no gender, no nationality, no age,” Entekhabi says. “I was looking for moments in which one is completely alone; for example, the sound of the shower or the scrapes of the razor. Then you suddenly notice something which brings you back to reality. At this point, you are once again confronted with your physicality, with the location, the environment. My work i? revolves around this search, the search for a ‘self.’”

At first, the nine young people in the workshop could relate neither to the subject of “identity” nor to a film language à la Beckett. According to Entekhabi, only during the practical realization were they able to display their true strengths. “Without consciously doing so, in the end they chose a similar film language to that of Beckett,” Entekhabi says. “In the process, an authenticity was created which some video artists are able to hide behind. However, these films don’t have anything to do with the subject of migration or being on the outside. These young people haven’t yet been confronted with their own ‘difference.’ Many are already from a fourth generation of immigrants and approach this subject in a very different way.”

Though he was happy to contribute to such a project, Entekhabi wonders if an exhibition such as “Far Near Distance” does the artists justice. “Naturally, at first it is nice to have the chance to meet so many artists from various branches. But something was missing,” he says, then with a sweeping arm movement, adds: “I think the reason was the composition. This is difficult. Artists who are completely different are suddenly thrown together in a show, in a room — and the only thing in common is nationality. But what does that actually mean? Examining this point could have been an interesting topic. But it didn’t take place. This isn’t a critique of the curator’s work, but more of a general problem with national-themed exhibitions.”

In these circumstances, Entekhabi feels that artists and curators tend to pander to societal expectations, rather than try to break new grounds. “If at all, I think such concepts should be taken on by several curators so that their various backgrounds and directions can influence the show,” he says. Entekhabi believes that when artists appear in a national exhibition there is always the danger that they will be pushed into the role of representatives. For him, it was important to transfer his connection to Iran as authentically as possible.

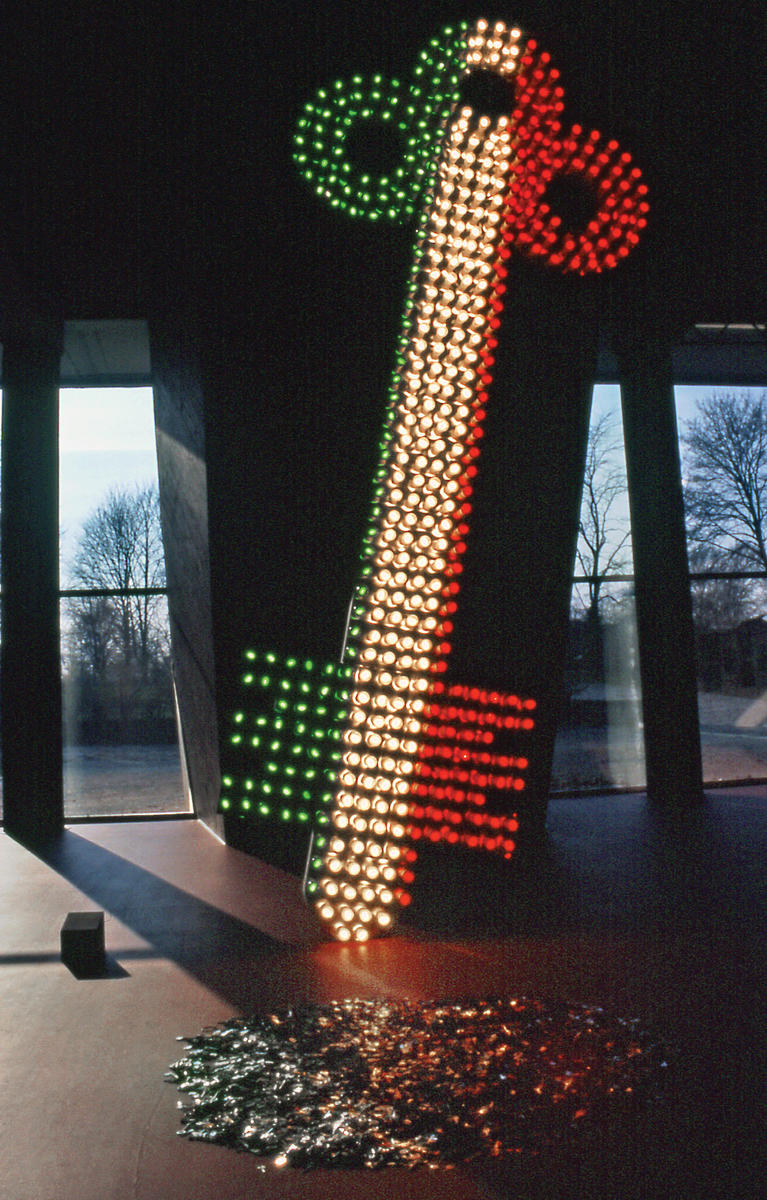

Entekhabi’s contribution to the show — an oversized, illuminated key in the colours of the Iranian national flag — provoked much discussion. The text next to the piece contained a misleading explanation, and many interpreted the work as the desire of a war refugee to return home, something that Entekhabi denies. “The explanation that I left Iran 25 years ago because of the war is false,” Entekhabi says. “At that time, I received a scholarship for my studies and simply happened to be in Italy when the revolution took place. Then there was no chance of my return.”

The oversized plastic key, according to Entekhabi, is actually an allusion to the promises of paradise. “I wanted to cite the idea of martyrdom, which exists in numerous ways and is used in political contexts,” he says. “The responsibility for this provocative cult of martyrdom is passed back and forth between Western and Oriental governments. Even if one can interpret different forms of sacrifice for a ‘good or holy thing’ or justify them, in the end it all comes down to forms of manipulation, symbolized by a promise. On the one hand, for a paradise in the life hereafter, and on the other, an ‘earthly’ paradise.” In Entekhabi’s video projection, a cacophony of pecking pigeons fills up the screen; the sequence lasts for a relatively long length of time. “For me, pigeons are the perfect example of being forced to adapt and of the ability to do so,” he says. “They are always there, yet have nowhere to which they really belong.” Does he see himself as a pigeon? He pauses, looking solemn, then says: “There are two people in me. One side constantly has the feeling of never really being part of that to which he could belong; the other is fully integrated. I never gave up my Iranian passport. Even after being married to a German. After 25 years in this country, I could have obtained a German passport, but I know that I will always be seen as an Iranian so why not officially remain one?”

www.pushthebuttonplay.com