London

Parastou Forouhar: Art, Life, and Death in Iran

Rose Issa Projects at Leighton House Museum

October 1–November 6, 2010

Parastou Forouhar’s first exhibition in the UK and a mini-retrospective of work ranging from 2003 to the present. Born in Tehran in 1962, Forouhar has lived and worked in Germany since 1991. Her exhibition catalog, made especially for this show, sets the tone for what is to come with a pithy, revealing epigram about the circumstances of her arrival in Germany: “I was Parastou Forouhar. Somehow, over the years, I have become ‘Iranian.’” This “enforced ethnic identification” (her words) is indeed a double bind, and swiftly becomes the point of departure for the works at hand.

In approaching the exhibition, one walks through Leighton House Museum’s Orientalist showcase, which centers on its nineteenth-century Arab Hall: a high-domed, indoor water garden, enclosed with intricately carved wooden screens, decorative tiling, and Qur’anic verse. Elsewhere are blue tiles, gold burnished ceilings, even a startlingly lifelike stuffed peacock in the stairwell. All the stuff of A Thousand and One Nights. Moving up the stairs to the galleries, one first encounters the series Signs (2004-2010), modeled on universal road signage. These pieces riff on repressive sexual hierarchies: pointing men to open doorways while directing women into holes in the ground. In reproduction they appear as mere kindergarten feminism. But however simplistic, these visual tricks managed to make me laugh out loud more than once.

Signs is not Forouhar’s strongest work, but it does signal a practice that will subvert orderly appearances. At the stronger and more enigmatic end of its spectrum is an installation called The Funeral (2003). The centerpiece of this well-constructed show, it fills an adjacent gallery with twenty-two everyday office chairs. Each has been dressed in a tightly fitted shroud, cut from colorful cloths made for annual Ashura processions in Tehran’s markets. Most are patterned with screeds of Farsi rendered in a range of calligraphic styles.

The Funeral is a startling piece of work. Taken individually, these monuments to unknown sitters strongly resemble stone-carved tombstones. Taken together, this strangely compelling funeral becomes a cemetery in which a group of people have been martyred, massacred, or bombed from above. What is unavoidable and overwhelming is the realization that they’ve all died at once. The piece is ominous, mesmerizing, and whispers of something having gone profoundly wrong. As it happens, the work was inspired by the murder of Forouhar’s parents, political activists, in 1998 at the hands of the Iranian state. The number of chairs, we swiftly learn, matches the date of their passing.

The remainder of the show is made up of elements of her work from the last decade. The earliest example, from her Eslimi (Ornaments) series (2003–2010), comprises fabrics, with patterns that reveal themselves too quickly to be made up of knives, knuckle-dusters, or male and female genitals. This single-dimensional trick recurs in Friday (2003) in which a fleshy hand shaped like a pudenda emerges from a chador — ta-da!

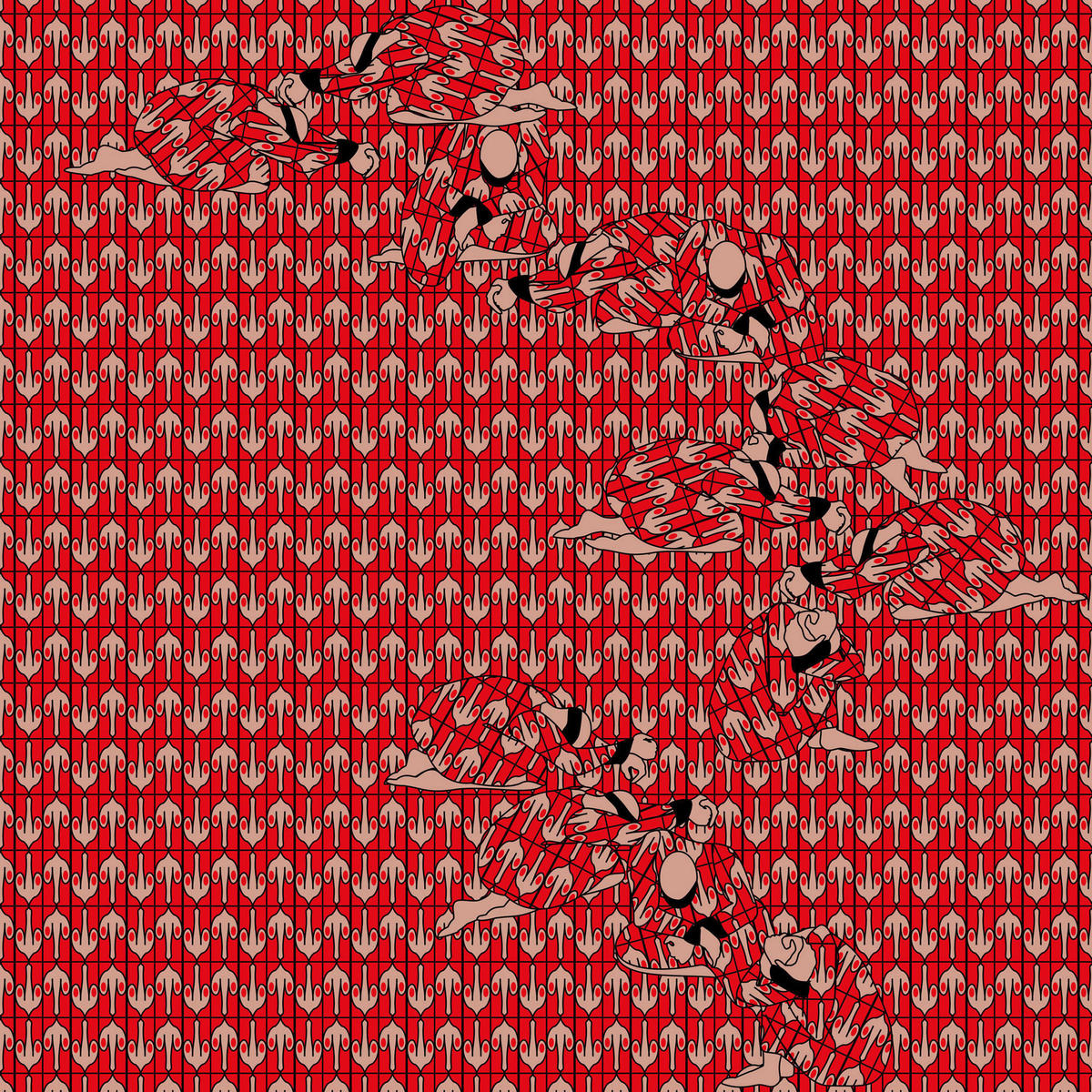

Elsewhere in the exhibition, two more series of eight digital drawings exemplify the later work’s layered complexity and steely clarity. Red is my Name, Green is my Name (2008) presents an apparently harmonious world of patterned surface. Look closer, and the pattern is again made up of tools of violence, as well as sexual organs. Look again, and bodies — blindfolded, restrained, hung up, or being pulled apart — emerge from already profane backgrounds. Bodies that have been tortured, slashed with knives, prostrate, and bound, in pain or in heaps. Meanwhile, there’s a hint of calligraphic abstraction in the black bindings, ropes, and restraints streaming across the picture plane. Momentarily, these figures emerge from the background before reverting to the realm of the unseen.

A second series entitled Thousand and One Day (2005) takes Forouhar’s obsessive re-workings of these elements to a new level. From a distance, they resemble Rorschach images or the skeletal remains of shark jaws, or a whale carcass. Closer still, and an exquisite pattern of similar figures — torturers and the tortured — emerge against monochrome backgrounds. That bony jaw is a figure being stretched or hung on a wooden rack; the whale carcass is a figure being pulled from both ends. Elsewhere, figures are bound, tied, leashed — expectant. Their throats are being sliced or they’ve fallen to the ground under prettily rendered lashes.

What is so striking in these last images is that instead of being lost to digital manipulation and abstraction, each figure seems ever more delicately individuated. This subtlety also rescues the work that appealed to me least on first encounter because of its simplistic iconography. Flag Collection — Knives, Revolvers, Grenades (2010) is the newest work on show: three large digital prints representing tools with stylistic hints at the Iranian flag. The best of these is Grenades, in which bodies that are crammed, bent into shape, and dressed in grenade-patterned cloths reach out to touch and hold each other. Even while crushed by potential violence, they seem braced for it together. Here pattern signifies a coming narrative, explosions of more than one kind.

Forouhar is evidently hyper-conscious of how the murder of her parents violently altered her life, and in turn, her artwork. The work is strongest when she invests her anger in subtle gestures, even beauty (itself partly Persianate) — when her ambivalence in life generates contrapuntalism in her art. Forouhar’s art of sinister beauty triumphs when it yields moments in which multiple dimensions, experiences, and, finally, emotions are at work at once.