“Go back to your souk!” is still the worst thing an aunt of mine in Milan can think to say to my uncle, who, like me, was born in Egypt. Fortunately, I have one right here in New York City, in a diminutive room you wouldn’t give two cents about. No one ventures into my souk but me. The local anthropologist calls it my “treasure house” and leaves it at that. When packages come from foreign places, he leaves them by the souk’s entryway without inquiring as to their contents.

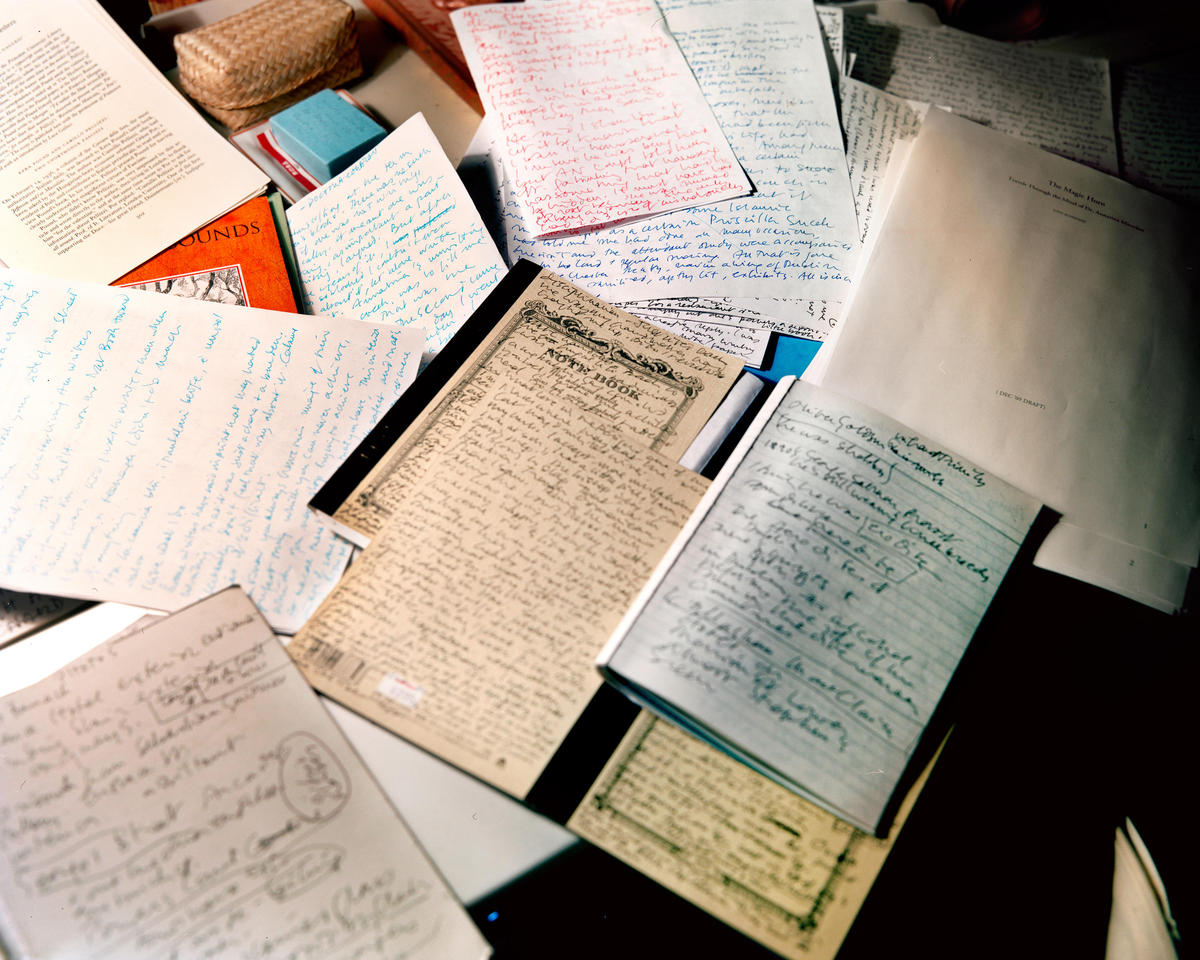

There is a window in my study-vault at the end of a narrow walkway between stacked containers, right behind the desk. I get a tremor of pleasure every time I walk by those clear plastic containers, which are called Iris and made in France — I can catch a glimpse of their insides without having to do anything so elaborate as opening them up. I come in here to work when I don’t want to be interrupted, but even more to be in a place filled with silent ornament. It makes me feel less alone, somehow, and it helps me to work, as well. I cannot explain it, but I’m certain of it — that this assemblage of threads, woven together with the thought of creating a pleasing pattern, can concentrate any mind that approaches it, and that this effect is similar to that induced by the mosaics of the Shayk Lutfallah Mosque in Isfahan and a thousand and one such places.

My little souk did not appear overnight. It took years to come together. I have come to think of it as a charity undertaken by a number of objects of various descriptions and origins, on behalf of one like me, born in Alexandria, and with a grandmother from Istanbul. They must have sensed that I suffered from a morbus of the eyes, a severe and progressive condition brought about by lack of beauty placed before them. Art can do its share of nurturing, in New York City as in Italy; but, as everyone knows, art goes straight to the mind. With a work of art, the eyes act as mere secretaries: they report who’s at the door, and furnish the briefest of descriptions, just enough to signal whether the visitor may gain admittance or not. No, I’m talking about the balm of ornament.

Until recently, I might have protested that ornament played no part in the life of an obdurate modernist like myself. Decades ago, working alongside an Italian designer who seemed unfailingly irked by curves and other femininities, I had willingly entered a universe of blues, blacks, grays, and whites — a convent of classical Western attire. There was no better place for an indoctrination into sobriety than Milan — except possibly Japan, where I’d gone to live when I was ten. In my five years in Tokyo, I’d absorbed Kuki Shuzo’s theory of iki — that impalpable taste for form and color in which a thing could be termed decent only if it was, at a minimum, virtually impossible to describe. And I greatly admired Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows. Staring long and hard into the bottom left-hand corner of La Main Chaude by Rembrandt, at a shadow shaped like the massive head of a German shepherd, right down to the ears, one notices it contains every variety of green-black, blue-black, gray-black — a thought to warm the heart of any iki adept.

Mind you, I may have dressed in men’s trousers, jackets, and shirts for years, but it wasn’t just me. The West forgot how to make ornament, even forgot to feel the need for it. When it did, it summoned up only the most ordinary of designs. In the language of ornament, one has to learn to say something more complex than the equivalent of “Nice dog” or “Good boy.”

But I was so dead set against ornament that ornament knew. It somehow knew that a direct assault would be ill advised, so it went about its work surreptitiously. In Aswan not three years ago, I visited the souk. I headed toward it thinking I would get a chalk-striped men’s djellaba such as I’d seen men wearing on the street. Can you explain why I returned with a pile of butterfly-hued cotton scarves?

First of all, I had not bargained on the salesman — or with him, for that matter. There are salesmen in souks, and one is as destined to one or two or three of them as one might be to one’s family members, friends, or associates. You find yourself drawn to their stalls, and there you stay. Then like djinns dancing out of their bottles, things begin to emerge from beneath piles on dusty shelves. You are taken by surprise. And you feel it is your duty to buy something. This is correct. You might have gone in thinking, “I’ll pretend to look, then I’ll leave and go find what I really came for.” But you have entered into a social contract — this is not mere consumption.

Later I realized that as I’d sat on the terrace of my room at the Old Cataract, admiring the sound of creaking doors and floors, surveying the miniatures on the walls of my room — veiled ladies draped over couches entertaining merchants bearing finery — I had answered a sort of call. A call to the souk — or, more precisely, to Mr. X’s stall. I was in a relationship with the gentleman, as surely as the veiled lady and the turbaned man who had probably plied her mother with wares, and no doubt her mother’s mother before her. I might have preferred the stall next door, or two doors down. But I would never know; I had been chosen.

I have no recollection of consciously deciding to correct my metaphorical scurvy, my souklessness. My body began to solve the problem by itself. After that first time with the scarves at Aswan, a more radical cure emerged one summer at my mother’s house in Strada in Chianti. I had finished writing an interview with an artist from Bangalore named Pushpamala N, who dressed up as the goddess Lakshmi, for instance, from the oleographic paintings of Raja Ravi Varma. An entire issue of the magazine was being dedicated to India. There was to have been an article on saris, too, which a friend in Chennai had agreed to write but could not complete. The editor suggested I do it. I had every good reason not to, principal among them that I didn’t know the first thing about the subject. But since that had never stopped me before, I agreed.

Gingerly, I went online to see what there might be to see of saris from my desk in Strada in Chianti. I had three days to write the piece. What there might be to see turned out to be hundreds and hundreds of saris. I fell down a hole and couldn’t stop looking. There were Bengali muslins with ribbon borders and jacquards with repeated intricate Islamic patterning, such as I’d seen on my grandmother’s collection of Turkish glass. There were swans in disciplined rows, swimming along borders, and colors conniving together that I hadn’t ever seen next to one another, like blue-gray with pale orange, or gold with cyan.

In a moment, I lost my minimalist compass — or rather, it was sent spinning by the multitude of designs set before it. It was as if I had sighted an oasis of color in a bleak desert of plainness and puce. Right there and then I dreamed of acquiring a thousand and one saris. The packages from foreign places began to arrive and took up residence in the treasure house.

Now I am entwined in ornament. It runs curlicues around my head and limbs and draws me back into the souk where I belong. Here in my dingy magical room, my eyes recover their power. The treasure house is a temple to those few left in the world who still know how to create an object for daily use that will enter the eyes and settle there, a burst of pleasure, given and received. In a souk in Marrakesh, a man who was angling to draw me into his stall of painted vases said, “Plaisir des yeux.” Pleasure for the eyes. I wouldn’t have to buy anything, he said. Oh, but I did.